A study of composting shelters on dairy farms has revealed a range of benefits besides the financial gains. By Anne Hardie.

Most farmers are noting financial gain from using composting shelters, but the real benefits revolve around animal welfare, people and the environment. In short, less pugging and pasture damage, happy cows and less stress all-round.

A study, led by Perrin Ag consultant Rachel Durie, also highlighted there is still much to learn about some of the basics of composting shelters such as the management of bedding. Farmers are leading the way in the adoption of the system, but there is a lack of quantitative data to support their onfarm findings on pasture growth, animal health and operating profit. She says figures will vary from farm to farm and depend on the individual farm’s starting point.

A study, led by Perrin Ag consultant Rachel Durie, also highlighted there is still much to learn about some of the basics of composting shelters such as the management of bedding. Farmers are leading the way in the adoption of the system, but there is a lack of quantitative data to support their onfarm findings on pasture growth, animal health and operating profit. She says figures will vary from farm to farm and depend on the individual farm’s starting point.

The qualitative findings are good though and the early adopters who have built a range of composting shelters on farms around the country are more than happy with the results.

“For a lot of farmers, it’s not just about the return they’re going to get from the shelters, but how it impacts on their work-life. Farming is not just a business.”

Durie’s study, Whole systems impact of composting shelters in New Zealand, was funded through Our Land and Water National Science Challenge under the Rural Professionals Fund 2021 and evaluated information from six farmers using composting shelters. The farms are spread between Waikato, Hawke’s Bay, Canterbury, Otago and Southland and have either rigid-roof or tunnel-roof designs for the shelters that are used for a range of herd sizes.

Alongside the six farms, the study also carried out modelling on a case study farm in South Waikato. That demonstrated several key benefits from potentially using composting shelters including a 45% reduction in nitrogen leaching loss, 33% increase in per-hectare cash operating surplus, 14% increase in milk production and a pre-tax internal rate of return on investment between 8.5% and 12.7%.

Alongside the six farms, the study also carried out modelling on a case study farm in South Waikato. That demonstrated several key benefits from potentially using composting shelters including a 45% reduction in nitrogen leaching loss, 33% increase in per-hectare cash operating surplus, 14% increase in milk production and a pre-tax internal rate of return on investment between 8.5% and 12.7%.

Durie says the desktop modelling indicated a composting shelter on the case study farm could provide an environment for land, animals, people and business to thrive. The farmers already using composting shelters are the real thing though. Those interviewed for the study consistently noted increased cow comfort and welfare, improved staff working conditions or improved labour efficiency, improved environmental performance and reduced pasture damage. It all led to overall increased satisfaction, less stress and increased pride in dairy farming as both a business and appropriate land use.

Whereas wintering had been, as one farmer described, “hard on people, hard on cows and hard on the soils”, they no longer worried about the weather and were enjoying the difference.

Between the six farms, the composting shelters are used either for an indoor-outdoor, year-round grazing system, or for a 24/7 indoor wintering system. In the first system, cows spend varying amounts of time in the shelters each day and the remainder of the day on pasture. Cows get shelter in winter and shade in summer which removes both cold and heat stress for animal welfare and lifts production.

Several farms had trigger levels for bringing cows inside during the summer months, usually between 20C and 24C. One farm had a system that enabled the cows to decide when to escape the heat and move inside. Once temperatures reached 20C to 25C, cows on that farm chose to head to the shelter, even when there was no feed there. Location influences the reasons for building composting shelters and Durie points out that South Island farmers are more likely to use the shelters primarily for wintering stock 24/7.

One farm that previously wintered a portion of the herd off the farm, now winters all the cows on the farm in shelters. Instead of a typical winter cropping regime, the farm solely feeds silage through winter to cows as well as replacement stock in the shelters between dry off and calving.

On all bar one farm – where a composting shelter was being trialled – the shelters are also used for calving.

The volume of imported feed also varied between farmers interviewed. One farm had increased the volume to become a high-input system, another reverted to a low-input system and the others have continued their usual feed system. Feed utilisation has improved and on some farms the composition of the diet may have changed with more land available for growing supplement such as maize and silage.

Durie says it shows composting shelters can be successfully incorporated within any feed system, and the profitability of the system after incorporation of a shelter is not constrained to a particular feed system.

The shelters can also be a tool for larger farm system change. One farm in the study reduced the herd size from 900 cows to 650. The stocking rate was maintained by incorporating more cropping into the system. A shift to autumn calving and winter milking occurred with the shelters providing flexibility and control of the system, particularly around pasture management and avoiding pugging.

The shelters can also be a tool for larger farm system change. One farm in the study reduced the herd size from 900 cows to 650. The stocking rate was maintained by incorporating more cropping into the system. A shift to autumn calving and winter milking occurred with the shelters providing flexibility and control of the system, particularly around pasture management and avoiding pugging.

It wasn’t the only farm to make system changes. Another farm previously wintered 710 cows and has reduced cow numbers to 530 to allow for all the cows to be wintered in the shelter along with replacement stock that were formerly wintered and grazed off farm. Outside of winter, the herd and replacements remain 24/7 on pasture on the farm. The changes have halved winter feed requirements with a large reduction in wastage and cow maintenance requirements. Silage is now harvested from the farm and used as the sole winter diet. That has removed the cost of grazing stock off the farm, winter cropping and purchasing feed for the transitionary diet.

Farmers in the study could list few disadvantages about the shelters, but an area of concern was the availability of bedding if demand outstripped supply. Bedding material varied between farms and in some cases changed over time with availability, cost and acquired knowledge.

Most used a fine wood chip-sawdust mix, while one farmer used solely sawdust and found its carbon content was too high which resulted in a fast composting and quicker replacement time. Some farmers have been trialling other options including miscanthus, with varied results.

Durie says one farmer found the miscanthus worked well as a top-up on the bedding and is now growing it on the farm with the aim of using it as the main bedding material. Another farmer had trialled it and found it composted too quickly.

Sourcing or finding ways to grow alternative bedding materials will be of particular importance to the long-term viability of composting shelters, Durie says. Managing the bedding is a necessary new skill for farmers working with composting shelters. She describes composting as a complex process that is impacted by the type of bedding material, stocking rate, shelter design, tilling management and how the shelter is used. Bedding temperature and moisture levels need to be maintained in the optimum range for successful composting. It needs to be regularly assessed and aerated.

Farmers in the study either monitor the bedding temperature and take drymatter samples, rely solely on temperature readings, or assess the compost visually.

“Understanding the key factors for successful composting and being able to implement a system that provides longevity in bedding material will be a driving factor for profitability.”

The aerobic composting process, which is characteristic of a well-managed shelter, mitigates the need for an effluent-capture system from the bedding. Three of the farmers interviewed in the study had built an effluent capture system beneath the bedding that linked in with the farm’s effluent system, but no effluent has drained out of the bedding. n other lessons, farmers with composting shelters have learnt there is a significant reduction in winter feed requirements compared with a 24/7 outdoor system. Feed requirements need to be well calculated to avoid cows gaining too much condition in the shelter and becoming too fat for calving. Cows were typically eating 8-9kg drymatter (DM)/cow/day at 95% utilisation which was a large reduction, particularly from farms wintering on crop where feed offered could range between 10-16kg DM/cow/day.

Durie says any large-scale build or system change will inevitably involve some trial and error or system adjustments. Some lessons learnt along the way will have minor ramifications that can easily be corrected the next time, while others could have very costly implications, particularly when it relates to the design of the shelter and management of the bedding. Getting these aspects right at the outset is critical and as one of the farmer participants said: “Do your homework and don’t take any shortcuts”.

Farmers are carrying out the trial work and Durie says anyone considering building a compost shelter should learn from farmers with prior experience.

She says continued pressure from society, markets and subsequent regulations will likely stimulate further farmer interest in composting shelters, but she cautions there is still much to learn about management and operation of the system onfarm.

When it comes to actual data, Durie says the farms are operating in a business rather than a research environment and many of the key metrics such as pasture growth, animal health and operating profit will be system and location dependent.

Composting shelter technologies and systems have not been incorporated within formal NZ research and development programmes. Instead, composting shelter development is being farmer-led. Because of that, Durie says farmers considering composting shelters need to undertake their own research before committing to a project to make certain the design will be fit for the specific location and purpose.

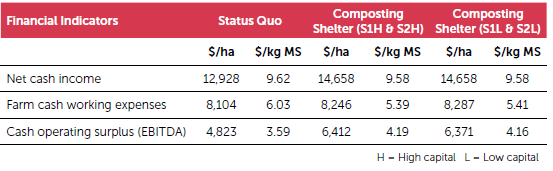

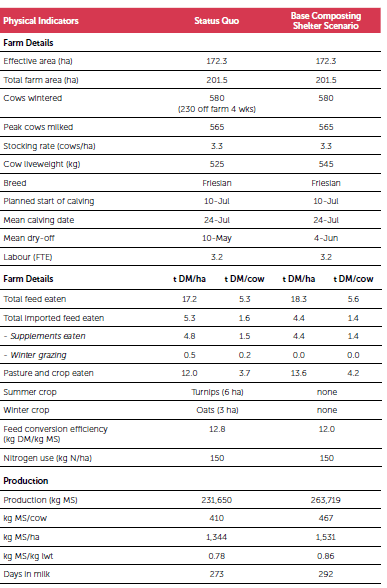

In the meantime, the analysis and discussion in the case study modelling provides a starting point. Kokako Pi Karere LP’s dairy farm in the South Waikato was used to create a status quo farm system to evaluate composting shelter scenarios. The 172 effective-hectare farm milks 565 cows. The modelling created different scenarios using rigid-roof designs and tunnel-roof designs and within each, high or low capital. These scenarios were then compared against the status quo farm system. The study is extensive and available online to look at the detail of the modelling, but the bottom line is the economics of all the composting shelters looked good. For the case study farm, the modelling showed an increase in the per hectare cash operating surplus of 33%, largely due to a 14% increase in milk production from improved feed conversion efficiency, improved pasture growth and mitigation of heat stress. In the case of heat stress, the modelling showed the shelters would add another 3820kg MS. That is worked out on 117 days of the year reaching a temperature-humidity index that would reduce milk production by an expected 6.8kg MS per cow per year from the 565 cows milked at peak. Simply, provision of shade in the shelters increased milk production.

As an investment, the modelling gave a marginal pre-tax internal rate of return (IRR) of 8.5% to 12.7% over a 50-year period, depending on the level of capital costs. At the whole business level, this provided returns of 6.8% to 7.4% compared with 6.3% in the status quo of the case study farm.

Durie says capital costs are largely influenced by structure type, extent of concrete and per cow spacing allowance. Key drivers of returns from the models included capital cost, bedding, milk price and production.

Additional milk production is needed in the scenarios to generate a greater return than the status quo on the case study farm. At $9/kg MS, the breakeven increase in production to generate the same return as the status quo system is between 31 and 43kg MS/cow, depending on capital costs. In situations where wintering in the shelters can remove significant off-farm grazing and intensive winter cropping costs, it may be possible to improve returns without any increase in production.

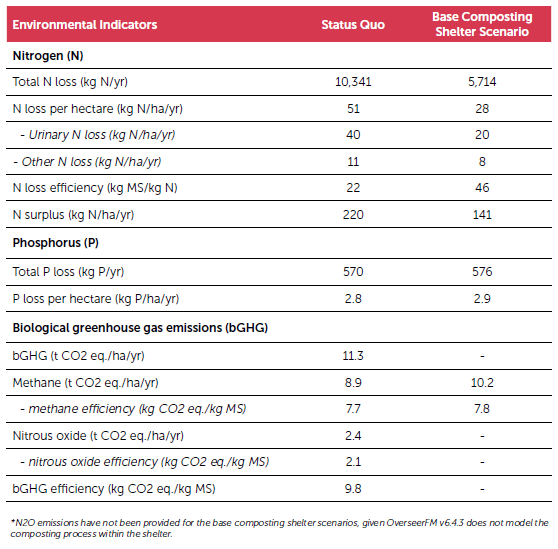

While the economics stacked up, the environmental performance in the modelling also painted a greener picture than the status quo. The shelters enabled a 45% reduction in nitrogen leaching, reducing overall nitrogen loss to water to 28kg N/ha/year. Nearly 90% of the decrease was attributed to reduced nitrogen leaching from housing the cows off pasture, with an average 6.6 hours spent in the shelter each day. The balance of the decrease in leaching was attributed to the removal of cropping.

Durie says modelling of greenhouse gas emissions from the composting shelters is more challenging as OverseerFM does not model the impacts of emissions from the in-situ composting process, nor the impact that provision of shelter has over winter on reduced maintenance requirements. Though all the case-study modelling and real-farm results appear to stack up economically, physically and environmentally, Durie says the composting shelters require significant capital expenditure and farmers need to carry out careful budgeting and analysis before they add them into their own farming system.