The world, and New Zealand, is getting hotter and weather patterns are changing as the heat goes up. By Elaine Fisher.

Robust evidence shows the Earth’s temperature is rising at a pace not seen before in its history and New Zealand farmers must take steps now to avoid the worst impacts.

That was the message delivered to those who attended the NZ Institute of Primary Industry Management (NZIPIM) Climate Change Seminar for Rural Professionals in November.

“Some say climate change doesn’t matter to New Zealand but that’s not true. It will have implications globally and for us. It will cost us to mitigate but cost us a lot more if we don’t,” Sinead Leahy, Principal Science Advisor New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre (NZAGRC) said during the seminar.

“There is still a wide spectrum of opinion about climate change including that the climate isn’t warming and we shouldn’t worry.

“However, it is very difficult to argue against the data which shows temperatures rising from the 1950s onward and increasing at a rate never experienced in our planet’s history. It is indisputable now that humans are causing climate change and Earth’s inhabitants need to be incredibly concerned about it,” Sinead said.

Fellow presenter Phil Journeaux, agriculture economist with AgFirst said as NZ’s climate changes, it might not be possible to farm in the same way as we do now.

“A couple of degrees of warming might not seem much, but it can have a big effect on pasture and crop growth and on pests, diseases and animal welfare. Ryegrass won’t grow at temperatures above 25 degrees.

“The upper North Island could go from a sub-tropical to a semi-monsoon climate with wet winters and hot dry summers. Friesian, Hereford and Angus cattle would be long gone in this scenario.

“Farming will be very different, and we need to sort out water policies because irrigation will be crucial in many areas.”

Designed to expand rural professionals’ understanding of climate change, why agricultural greenhouse gas emissions are important in NZ, how they can be estimated within the farm system, and how they can be reduced on different farms, the all-day seminar, was attended by 25 rural professionals from around the country. Nearly 40 of these seminars have been held since mid-2019, attracting more than 670 people.

The seminar sought to answer some of the questions rural professionals most often heard from farmers including around animal emissions, methane and carbon sequestration.

A frequently heard comment was that there had always been large numbers of ruminant animals on the planet emitting greenhouse gases.

“The number of ruminant animals in the world has never been greater than today. In North America it’s estimated there were once 70 million bison but today there are more than 200 million cattle in the USA,” Phil said.

“In New Zealand if you go back a few hundred years there were no ruminant animals here. Today we have around 40 million in NZ and those growth trends have happened all around the globe.”

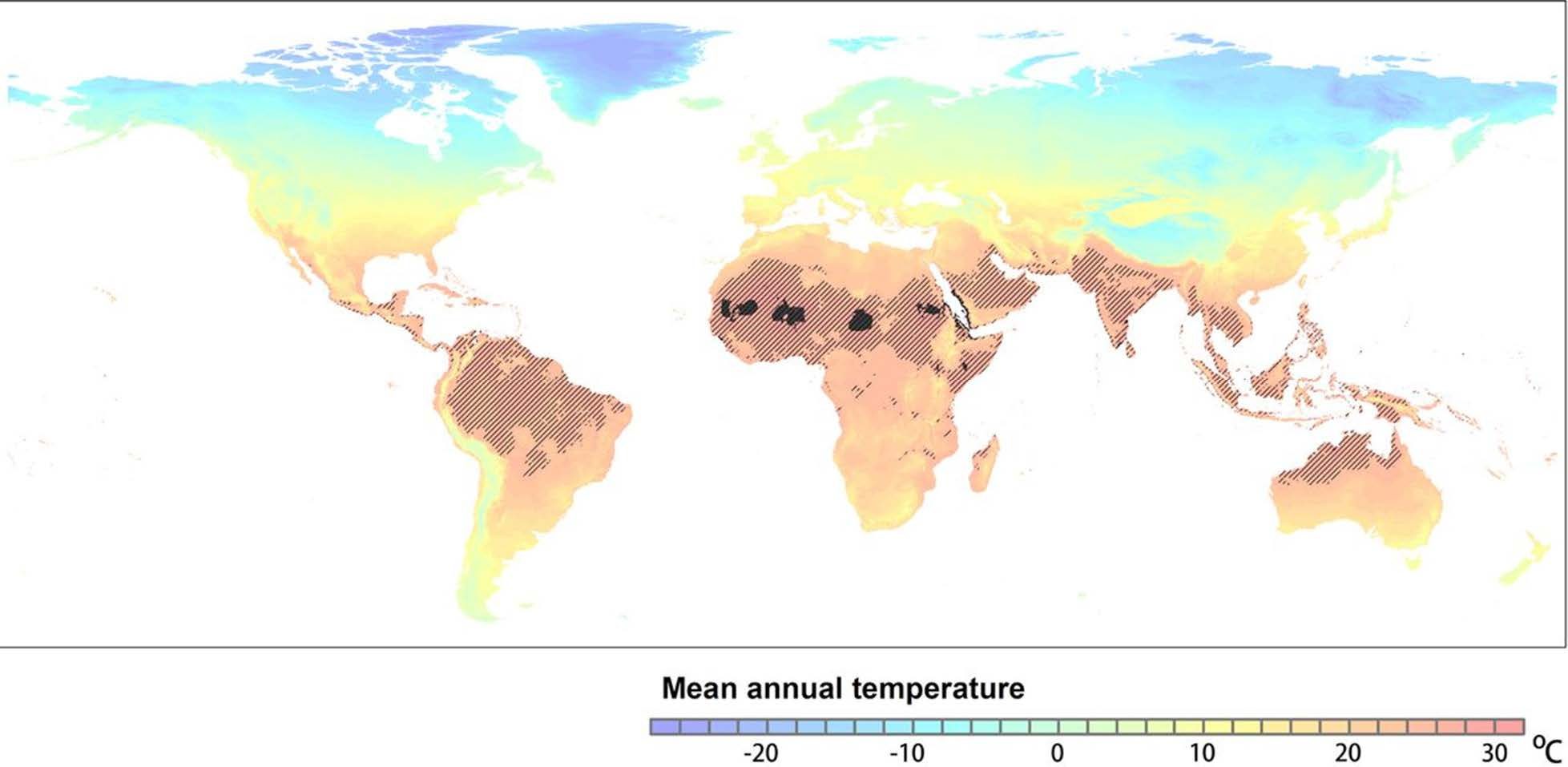

today. In cross-hatched black are the areas that will be too hot for humans by the year 2070. Such areas

include some of the most populated regions of the globe. Source: “Future of the human climate niche”, Xu et

al, PNAS 2020.

Another argument was that methane doesn’t matter or that methane and nitrous oxide make an insignificant contribution and should not be targeted in any national framework for reducing emissions.

Sinead said although methane (CH4) is a short-lived gas, it does matter when it comes to limiting global warming.

“Methane can have a very important role to play in reducing climate change. New Zealand is the first country in the world to acknowledge that not all greenhouse gases are the same. There are different targets for different gases in New Zealand, recognising the different warming effect of methane in the atmosphere.”

The Government has legislated long-term targets to reduce NZ’s greenhouse gas emissions, including that carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide (the ‘long-lived’ gases) need to reduce to net zero by 2050. Methane emissions are to reduce to 10% below 2017 levels by 2030, and 24-47% below 2017 levels by 2050.

However, in the scenarios for achieving the goal of limiting warming to well below 2°C, in contrast to carbon dioxide emissions, methane emissions do

not need to go to zero. Methane has several sources, including wetlands, landfills, forest fires, agriculture and fossil fuel extraction. In NZ, the largest proportion (about 95% of total methane) is belched out by livestock. This is known as ‘enteric methane’.

The average dairy cattle beast produces about 98kg of methane a year, the average beef cattle beast produces 61kg a year, the average deer about 25kg and the average sheep about 13kg a year.

Nitrous oxide is emitted into the atmosphere when naturally occurring microbes act on nitrogen introduced to the soil via dung, urine and fertiliser. Nitrous oxide accounted for 11% of NZ’s total greenhouse gas emissions in 2020, the largest source of which came from livestock urine and dung.

NZ dairy farmers had become very efficient in increasing milksolids per cow through means including better genetics and pasture management, Sinead said.

“We do know if farmers farmed the same way now as in 1990, instead of 17%, our total agricultural emissions would have increased by about 40%. Farmers have made a lot of efficiency gains which have nothing to do with climate change but with their bottom line. Efficiency gains still have a role to play in reducing absolute emissions,” she said.

Overall, NZ’s emissions are small at just 0.17% of global gross emissions (22nd among developed countries). However, per capita our emissions are the sixth highest in the world.

Sinead said some people argue that reducing NZ’s emissions is perverse.

“They say that if we reduce production here with a price on agricultural greenhouse gas emissions, other, less-efficient, producers will increase their production and total global emissions will go up. But it’s not quite as simple as that.”

Many of NZ’s competitors produce similar emissions per unit of product and have national mitigation targets to meet. If they expand their agricultural production, emissions must reduce somewhere else in their economy. Competitors in the developed world also face constraints on production. There is scope to maintain production and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“We are a trading nation and produce more food than required by the five million people who live here. We export close to 90% of the food we produce and as a result we are dependent on what our customers want. Our big clients like McDonalds, Nestle, Danone and Tesco are all facing regulations in regards to climate.”

For many of NZ’s customers, a significant proportion of their greenhouse gas emissions will come from their farmer suppliers so it is likely they will impose emission reduction targets for them to meet.

Phil said some farmers asked why they could not claim carbon credits for the grass they grew.

“Grass removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as it grows but returns it to the atmosphere when it is harvested and utilised,” he said.

Trees do exactly the same. However, the interval between growing/harvesting grass is weeks, whereas trees are harvested after decades or centuries – or not at all. The same quantity of carbon is stored in grass at the start and end of each year. The quantity of carbon in a tree increases year on year, while the tree grows.

The seminar spelled out clearly that NZ’s gross emissions are increasing and why action to reduce them is crucial.

In 2020, NZ gross emissions were 78,778 kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2-e), comprising 44% carbon dioxide, 44% methane, 11% nitrous oxide and 2% fluorinated gases. This represents a 21% increase in emissions since 1990 (which is when international reporting obligations for greenhouse gas emissions began).

In 2020, 73.1% of NZ’s reported agricultural emissions was enteric methane from ruminant animals. A further 20% of agricultural emissions was nitrous oxide, largely from the nitrogen in animal urine and dung, with a smaller amount from the use of synthetic fertilisers. The remainder of agricultural emissions in 2020 were mostly methane from manure management (4.4%) and carbon dioxide from fertiliser, lime and dolomite.

For more information on the topics covered in this seminar, please see www.agmatters.nz

Climate change projections for New Zealand

Many places will see more than 80 days a year above 25C by 2100, which will have a significant impact on ryegrass growth (it prefers temperatures of 5-18C) and animal performance

Winter and spring are very likely to have increased rainfall in the west of the North and South Islands and be drier in the east.

Summer is likely to be wetter in the east of both islands, while the west and central North Island will be drier.

All areas are likely to get more very extreme rainfall, especially shorter, more intense events.

Increased drought frequency in many regions of New Zealand and farmers in dry areas can expect up to 10% more drought days by 2040.