Colostrum is the essential ingredient for newborn calves to survive and thrive, Paul Muir writes.

Failure of calves to get sufficient colostrum and acquire early immunity is a worldwide problem. New Zealand studies have shown 25% of one-day-old calves have had no colostrum and up to 40% have not consumed enough colostrum.

It is critical that a calf gets high-quality colostrum within the first 24 hours and, preferably, within the first 12 hours.

Calves with inadequate immunity from colostrum are four times more likely to die and those that survive have lower weight gains, poorer feed conversion efficiency and a higher incidence of scouring than calves with good levels of immunity gained by drinking good quality colostrum in their first 24 hours.

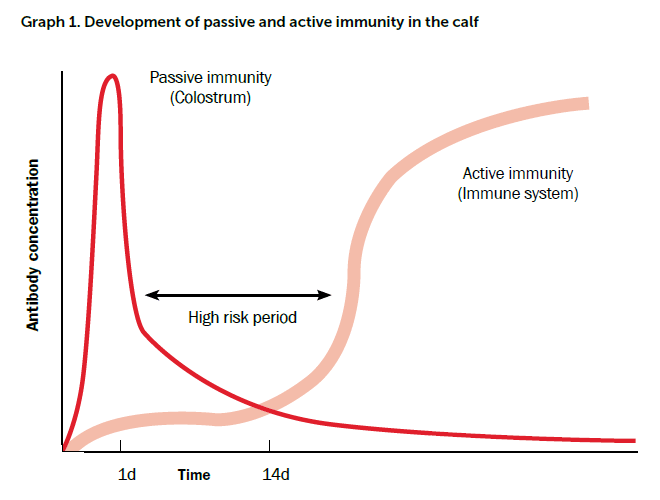

Calves are born with a very immature immune system and immunity is obtained from the cow through immunoglobulins in her colostrum. These immunoglobulins are large protein molecules which can only be absorbed and move through the calf’s intestinal wall for the first 24 hours after birth.

By this point the wall of the small intestine has matured to the point that these large immunoglobulins can no longer pass through. In addition, the secretion of digestive enzymes starts 12 hours after birth, these enzymes digest and break down immunoglobulins rendering them useless.

The young calf is born with no resistance to diseases like E. coli and salmonella, so it’s only protection in these first few days is from colostrum (this is called passive immunity).

A calf with no immunity can get sick when challenged with just 500 salmonella bacteria, whereas one that has received a good level of passive immunity can withstand 10 billion salmonella bacteria.

By the end of the first week the calf is starting to build its own immune system and produce its own antibodies in response to pathogen challenges. Within a few weeks the calf is well on its way to being able to fight off disease.

Why do calves miss out on colostrum from their mothers?

While many calves get colostrum from their mothers, a lot don’t. The practice of removing calves from dairy cows for generations has undoubtedly reduced the cow’s mothering instinct. Some dairy cows are apt to wander off soon after calving. Calves can go under hot wires and selection for milk production means that some udders are low and difficult for calves to access.

Six hours after birth, around 25-30% of dairy calves will not have suckled and 20% still will not have not suckled within 18 hours. Daily calf collection (if not twice daily collection) is the right thing to do – however, do not assume that the calf has had enough colostrum from its mother before you pick them up. New arrivals to the calf shed need to be fed colostrum unless you are sure they have had colostrum from their mother. Waiting until the next day when they will be “hungry” is too late. If necessary, the calf should be tube fed although this reduces the efficiency of absorption of the antibodies.

The amount of protection a calf obtains from colostrum is determined by the amount of antibodies ingested and the amount that is absorbed. The amount ingested is affected by the volume of colostrum consumed and the concentration of the antibodies in the colostrum. The calf should get 5-6% of its bodyweight as colostrum in the first six hours and the same amount 12 hours after birth to ensure that at least 100g of antibodies are consumed. This equates to about 2 litres of colostrum per feed for a 40kg calf.

Factors affecting the quality of colostrum

Antibody levels are highest in the first milk produced after calving and then drop rapidly so colostrum fed to calves in the first 24 hours should be first milking colostrum only (see graph 1).

Antibody concentration varies between cows with a DairyNZ study showing an average of 48g/litre but with a range from 20 to 100g/l. Ideally, a calf should be fed first milking colostrum from a mixed age range of cows — to give the calf a wider range of antibodies. Cows which have been vaccinated (e.g. against rotavirus) will produce more antibodies to the pathogen they have been vaccinated against. Cow breed, age, her exposure to pathogens and nutrition all affect the quality and volume of antibodies.

Feeding energy-deficient diets prior to calving reduces both production and quality of colostrum. Generally, dairy breeds produce more total immunoglobulins than beef breeds and older cows produce more immunoglobulins than heifers as they have been exposed to more diseases.

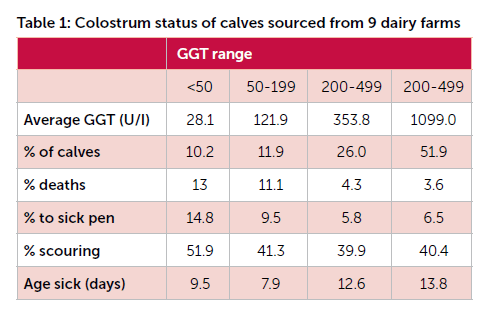

In another study, we bled calves on arrival from 9 dairy farms to look at colostrum status. GGT less than 50 indicated no colostrum and GGT levels between 50 and 200 indicated marginal colostrum. About 22% of calves had nil to marginal colostrum. Death rates were higher in the no colostrum group (13%) and the “inadequate colostrum group (11.1%) than in the “good” colostrum groups (4%). (see table 1).

There was variation between source farms in apparent colostrum intake, with a range in mean GGT (colostrum) levels of 360 up to 942 U/l. Calf mortality ranged from 1.2% up to 12%. The farms with the lowest colostrum intake had the most calves in the sick pen and the highest mortality.

When we looked at colostrum level by arrival batch, it was clear colostrum level was declined as the season progressed. Calf rearers often experience having more sick calves as the season progresses. This has generally been put down to a build-up of bugs through the season as the shed gets dirtier and the weather warms. Yet here is evidence that declines in calf colostrum status may increase the risk of calves getting sick. Presumably, this is due to a decline in standards on the dairy farm as the season progresses.

Sick calves

Most problems occur in very young calves and by the time calves are two to three weeks old and eating pellets the incidence of problems drops dramatically. An early indicator of a problem is often scouring. There are three possible causes – stress, nutritional (both management issues) and infectious agents. There may be more than one causative agent and identification of the actual cause is often difficult. The number and timing of calves scouring is often a clue as to the cause.

- More than 40% calves scouring: Often an indication of a problem with the milk. May not be curding, the concentration may have been mixed wrongly or too much is being fed.

- Between 5% and 40% calves scouring: Often an indication of cryptosporidia infection. This is caused by a protozoa which is widespread in calf sheds. It particularly affects young calves up to 10 days of age. The infection builds over a few days and can affect a significant proportion of calves in the shed. The treatment is to remove from milk and feed electrolytes for a day.

- Less than 5% calves scouring: A few scouring individuals is often the sign of something more sinister – particularly if they go down very quickly. Consult your veterinarian. Potential culprits are rotavirus and salmonella. Isolate and treat with electrolytes. Salmonella is caused by a bacterium and can be treated with antibiotics. If a recurring problem on the property then young calves can be vaccinated. Often rotavirus and salmonella are secondary to a cryptosporidia infection which makes treatment more difficult.

Stress scours. Can be caused by difficult birth, bad or sudden change in weather, transport, environment (e.g. over-crowding, cold, damp, draughty or humid conditions inside calf sheds).

Even changes in staff and hygiene can increase the likelihood of scours. The stress of transporting calves from the sale yards or from one farm to another may be sufficient to cause scours if calves are offered milk on arrival. Newly arrived calves should be fed an electrolyte.

Nutritional scours. Often caused by overfeeding or by a rapid change from colostrum/milk regime to a milk powder regime. The initial digestion of milk occurs in the abomasum (or fourth stomach) and then in the intestines. Nutritional scours is due to inadequate milk digestion in the abomasum. This means the milk leaves the abomasum too early and overloads the intestine with lactose. This results in a watery scour and the fluid loss results in a very dehydrated calf.

Infectious scours. Caused by a range of pathogens including cryptosporidia, coccidia, salmonella, E coli and rotavirus. But generally, the better the immunity obtained from colostrum, the better the calf copes with disease challenges. In a calf that has had inadequate colostrum as few as 500 salmonella bacteria can result in a sick calf while a similar calf with an adequate colostrum intake can cope with as many as 10 billion bacteria before it gets sick to the same degree.

- For more information www.on-farmresearch.co.nz or facebook – NZ Calf Rearing Discussion

- Paul Muir and fellow researchers from On-Farm Research, Poukawa, Hawke’s Bay have been researching the calf rearing market and strategies since 1996.