Fake meat and other alternative proteins are growing in popularity as consumers take into account climate change. But Phil Edmonds finds reasons to doubt the threat of alternative proteins and sees the opportunity for New Zealand food producers.

Evidence has emerged recently suggesting NZ food producers are losing interest in the threat posed by alternative proteins, and the impact their further development could have on demand for our pastoral agriculture. This diminishing concern (if it ever was elevated) comes despite no let up in the global investment in ‘new food’ designed to reduce the need for animal protein, along with relentless enthusiasm for its climate change-busting qualities.

Are we right to rest easy and accept the threat is misplaced or overblown, or should we instead be thinking how alternative proteins present NZ farmers with an opportunity to diversify, and build resilience in their business? The answer might come down to how much the government can be convinced that alternative proteins align with its vision of growing the value of New Zealand’s food production.

Each year in June KPMG publishes its Agribusiness Agenda which, based on responses from industry players and stakeholders, identifies the most important issues facing the sector.

The Agenda ranks the issues and compares the results with previous years. Noteworthy in this year’s findings was ‘tracking the global evolution of alternative proteins’ experienced the second largest decrease in priority among all issues considered.

The explanation given by KPMG was the fall in priority might simply be due to the sector coming to terms with the emergence of novel foods and the new competition for traditional commodities does not pose the same sense of fear as it has done in the past few years.

It may however be that farmers and the wider food producing sectorfeel like they have more immediate concerns than the pressures posed by new alternative foods.

Not only have there been Covid-19-related to disruptions to deal with (access to imported materials and labour), but the Government’s legislative programme to address climate change and water reform is also an increasingly pressing preoccupation.

And on top of that, the current robust demand for New Zealand’s existing agricultural output is not helping to train thoughts on a world where pastoral production is under threat.

FEEDING OUR FUTURE

There are also other reasons why farmers might be feeling justified in ignoring the perceived danger.

A recent ‘dialogue’ hosted by Massey University’s Riddet Institute on ‘Feeding our Future’ included presentations of now familiar arguments on why alternative proteins won’t take hold anytime soon.

Monash University biotechnology professor Paul Wood suggested that cost of production rather than consumer curiosity would determine the potential for plant fermentation and cell-based meat to take hold.

Wood said the cost of facilities (pharmaceutical grade, in ultra clean, air filtered rooms) for fermented proteins means a litre of ‘product’ could cost $3 for the protein alone (before components to make it ‘consumable’ are added). This compares with the global average cost of producing ‘ready to consume’ cow’s milk currently sitting around 45c.

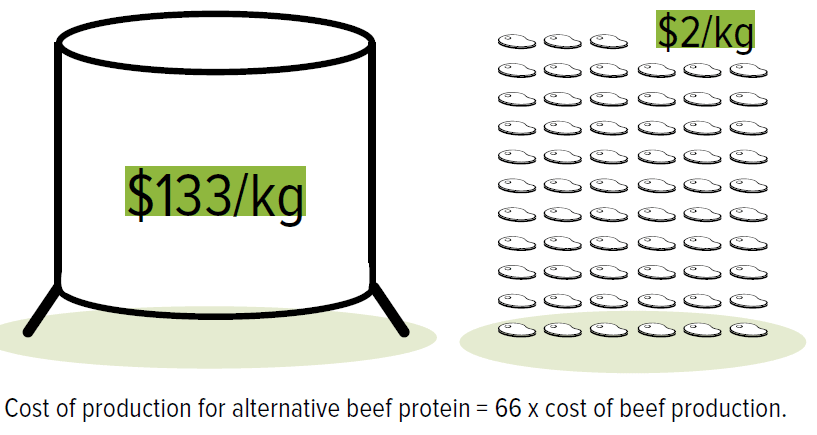

Similarly, for cell-based meat, Wood estimates using high-spec production facilities at a large scale (10 kilo tonnes of output for example) would cost $133 per/ kg, compared with a global price of beef production at around $2 per/kg.

There is an obvious counter argument to this challenge – once upon a time computer chips started out with similar cost deficits, and they did eventually fall. However, Wood says computer chips are physical products, not biological. “Can costs come down closer to livestock production? Personally, I don’t think it will happen.”

CONSUMER BEHAVIOUR

A further reason to doubt the immediate threat of alternative foods was delivered by Massey University food science academic and Riddet Institute chair in consumer and sensory science Joanne Hort, who says consumer acceptance of new foods can not be assumed.

“If you look at the marketing of new foods, you might assume there has been a strong uptake. But what consumers say and what they want doesn’t translate into behaviours.”

Based on an understanding of what drives consumer behaviour, new foods will need to be cheap, have an appealing texture and be convenient. These factors rank more importantly than any values (such as animal welfare and the environment) that consumers hold.

Hort said consumer decision making is not rational. “95% of decisions are driven by instinct, not values or attitudes. Any effort to make sustainable diets more attractive would need to make new foods more appealing (tasty), effortless to access and consume and be ‘the norm’ rather than the exception.”

Collectively, awareness of these arguments might have contributed to more complacent attitudes, but are they enough to prohibit further thinking on how New Zealand can participate?

For a start, Fonterra has accepted that plant-based milks are here to stay and are not just a Silicon Valley thing. Fonterra has

recently reported it is actively working out how it could participate in the plant-based milk space. And publicly at least, it sees no point in starting a defensive ‘bovine-milk good, plant-based milk bad’ campaign. Fonterra clearly sees growth potential, and importantly, as a key global player in milk products, does not want to be left behind.

While KPMG has reported falling industry interest in alternative proteins, the consultancy firms’ manager for agrifood research and insights Jack Keeys is keen to project their importance and promote the potential for New Zealand to play a role in their future development. In the Agenda, Keeys suggests this could be possible with evolved thinking on the demand for alternatives. Rather than alternative protein, he says we may be better served by focusing on delivering ‘alternative nutrition’, a more complex deliverable than simple protein requirements. Whatever the nuanced terminology, those with an eye on the future are steadfastly convinced NZ still needs to plan ahead and take note of the likes of Impossible Foods founder and CEO Pat Brown, who in July told the Washington Post his company has pledged to “eliminate animal agriculture in the next 15 years… put it on your calendar, Impossible Foods is going to do it.”

EMERGING PROTEINS

With a glass half full attitude, and to help better understand the opportunities, government and industry-funded food science and innovation hub FoodHQ published a report Emerging Proteins in Aotearoa New Zealand in April. The Government as much as food producers and manufacturers wants to understand if the ‘potential to play’ exists, and like Fonterra, does not want to be left behind should that be the case.

Among nine observations made in the report, the emerging proteins sector was seen as a potential solution for farmers and growers. This was based on farmers looking for opportunities to future-proof their businesses through enabling better financial and/or environmental performance.

The report said, “For many animal farmers, interest has been stimulated as part of an evaluation of potential responses to tightening environmental limitations (either now or expected in the future).”

There is certainly evidence of this, although it is still for the most part, at an experimental stage.

Golden Bay dairy farmer Wayne Langford has planted a wheat crop as part of a planned introduction of farming practices to help run his farm more sustainably. Planting the crop was undertaken based on its potential financial viability, with the wheat destined for use at a local bakery. Both these motivations align with the anticipated interest identified in the report.

While the wheat crop is not part of a strategic decision to produce alternative proteins, Wayne has a pragmatic rather than dismissive approach. “We are going to have a shortage of protein in the world as the population increases, and it doesn’t matter if it is plant-based or animal protein. As the world grows and changes, we will be given different opportunities, and this will be one of them.”

Beyond experimenting, the FoodHQ report notes there will be a right and wrong way to enhance the potential of success of an emerging proteins sector. This includes only proceeding when a clear market exists that will return enough to make it profitable and avoiding growing a crop ‘just because you can’.

Producing ‘at scale’, which to date has been recognised as a prerequisite of success, certainly seems out of reach at the moment, and this still poses reasonable doubt over whether NZ can ‘play’. But the report also notes that NZ has a long tradition of taking on the world despite the odds. One final thought that should keep farmers’ minds open – the Government’s willingness to support an emerging proteins industry.

Where the Government is concerned, all public investment starts by ticking boxes in its ‘Fit for a Better World’ vision for the future of NZ’s food and fibre production. If alternative proteins can play a role in helping to define NZ’s regenerative farming system, measurably reduce primary sector carbon emissions, be exported as high value products to a well identified consumer market, make farm businesses more resilient and increases the attractiveness of the primary sector as a career pathway, then… apply for funding now!

Ultimately, the decision will comedown to whether you believe, like Monash University’s Paul Wood, that based on the high costs, alternative proteins will be a ‘niche product’ likely to serve discerning middle to high income consumers, (in which case watch this space), or Impossible Foods bullish commitment to create affordable food for everyone.