A Manawatu couple were keen to try regenerative practices on their dairy farm, then decided to go the whole way with a switch to organics. By Jackie Harrigan.

Darryl and Debbie Coleman are Kimbolton dairy farmers on a regenerative and organic farming mission to front-foot changes in the industry and operate a farming system that is focused on cow and soil health and economic resilience.

Darryl and Debbie Coleman are Kimbolton dairy farmers on a regenerative and organic farming mission to front-foot changes in the industry and operate a farming system that is focused on cow and soil health and economic resilience.

Always pragmatic and numbers driven, they have introduced robotic technology while also embracing a new farming philosophy.

“We are just going about our operation but are doing a few things that are out of the conventional path and potentially going down the track where the perceived markets are – for our own interest and to front-foot changes in the industry we see potentially coming,” Darryl explained.

The couple have been dairy farming for 30 years and “were just doing the same old, same old,” he said.

The new journey, while not straightforward, is providing a new spice of life and they are enjoying the problem-solving and learning aspects of the new direction.

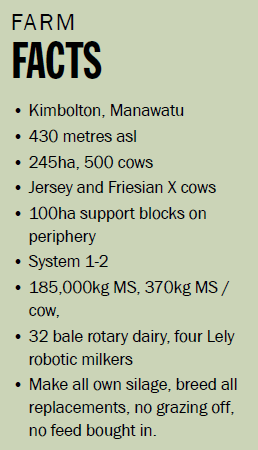

Several threads led to their change in direction on the 245-hectare, 500-cow North Manawatu farm. The first was a desire to be more resilient and self-contained, and maximise soil and animal health, which led to the regenerative move three years ago.

Transition to organic status started almost three years ago and the operation will be fully certified by January 2023, Darryl said.

“Biogro certification allows us to supply into all of the organic markets that Fonterra wants to sell into – European Union, China, Korea, North America and Taiwan.”

“The number of organic dairy suppliers is relatively small when compared to conventional suppliers but Fonterra are actively growing the supplier base now.”

Debbie remarked they have also noticed that the organic certification and audit process appears to be getting more holistic in what organic means – talking about staff safety, noticing recycling and rubbish disposal, measuring calf pen space and cow welfare, and other metrics beyond the usual checks around the use of fertiliser, antibiotics and chemicals.

“That might be coming through from the markets – consumers are looking deeper into how and where their food is being produced,” Darryl said.

Their regen journey started when they realised they have always had a bent for the ‘healthy soils, healthy animals’ philosophy, but without really knowing the science behind it.

“We have always been low users of nitrogen and synthetic fertilisers and been less intensive than others, but we wanted to improve our soils so went to a workshop with Nicole Masters, from Integrity Soils, and then shortly after that heard Australian soil scientist Christine Jones talk.

“That linked a lot of stuff that we didn’t know about soils and soil life and we felt that for the first time we received advice independent of a sales push. That was the ‘light bulb moment’ for us.

“It put some science around how to get our soils working for us and it really made sense and lit up our interest in doing things a bit differently.

“Then we started to realise that the changes we were making to adopt a regen system was not that far away from an organic system, so we decided we might as well go the whole way and do organics as well.”

Robotic milking centralises milking

The other thread for change was the desire to cut walking distances and milking times for their cows. Historically, the 500 cows were milked in two herds through a 32-bail rotary dairy shed at the top end of the farm. Debbie calculated she was spending the equivalent of six working weeks a year sitting on the quadbike bringing the second herd of cows up 1.8km from one end of the farm to the dairy shed. That contributed to the decision to build a second cowshed in the middle of the farm with robotic milkers, which would hopefully cut the time inefficiencies and energy losses through so much walking.

The other thread for change was the desire to cut walking distances and milking times for their cows. Historically, the 500 cows were milked in two herds through a 32-bail rotary dairy shed at the top end of the farm. Debbie calculated she was spending the equivalent of six working weeks a year sitting on the quadbike bringing the second herd of cows up 1.8km from one end of the farm to the dairy shed. That contributed to the decision to build a second cowshed in the middle of the farm with robotic milkers, which would hopefully cut the time inefficiencies and energy losses through so much walking.

The choice to go robotic was also driven from the improved cow health and production data captured, and allow the couple to monitor the herd much better.

Debbie is the animal manager part of the Coleman’s partnership, alongside Darryl’s machinery and infrastructure focus – but, having both initially trained as accountants, they share a love of numbers and monitoring.

“Our interest in the numbers around the farm – the inputs and outputs, led to thinking that robots might be the way to go, and that the two dairy systems could work in together.”

So the robotic milking shed was set up in the middle of the farm, with paddocks fanning out down three laneways around it to allow the cows to voluntarily move from one break to the next, with three automated gate changes occurring each 24-hour period. The farm is now essentially split into two grazing zones, one for each cow shed, although all the cows start the season going through the rotary until they are through their colostrum period (PSC 20 August).

The robotic shed starts up about September 1, when there are enough cows calved to make a second milking herd. The robot-trained cows are then transferred to the robot shed. The heifers stay in the rotary herd for the whole season, then a selection of them that are deemed suitable for the robots are trained as replacements for the robots in their second season. The selection criteria for the robots focus on teat placement, milking speed and temperament.

Twice-yearly herd testing all happens through the rotary shed with the robot herd coming back to the rotary for a two-day period. Debbie has taken the opportunity to test for both Johnes disease and pregnancy testing from the herd test sample. Darryl and Debbie are happy with the way the dual shed system is working and have sorted a system for breeding replacements from both sheds. AI is used for 3.5 weeks using A2/A2 Jersey bulls and then homebred bulls are put out with the herd.

Traditional tail painting and Bulls-i “stickies” are used for the rotary herd, but the robot herd relies solely on the heat detection functionality built into the cow collars and the robotic milking software. Cows in heat are then automatically drafted off by the robots at a set period in the day, so they are ready for the AI technician.

“We found virtually no difference in the conception rates for the two herds, so it was reassuring that we could rely on the technology to do its job,’” Darryl said.

A cow that is new to the robots takes about a week to learn the system. The bulls also need to learn how to negotiate their way through the robot gates, and seem to do so in a couple of days by following the cows.

“We always knew the cows were intelligent but probably have never given them enough credit for how smart they really are.”

The animal behaviour aspect of robotic milking is fascinating, Darryl said.

The cows begin to act more like individuals rather than following the pack and will come and go from the robot shed as they please. Some also get very canny about the break change times and deciding whether the walk through the shed is worth it.

The 220 cows are given a small amount of organic molasses in the milker, about half a cup as an incentive to come to the shed, but some cows quickly work out when the break changes occur that allow access to a fresh paddock. Some of the eager ones wait in the yard or lane until they see or hear the gate change and then they begin moving.

The robotic milkers have not really saved the Colemans any labour, as they are still operating the rotary shed, but they say there is now more time to focus on and fine tune management, to monitor the pastures and telemetry checking on the cow health.

“We are constantly monitoring something – the pastures, the break sizes, animal behaviour and the robotic machinery.

“The robots have put us in the driving seat with a lot more information and made us more numbers driven. We like the inputs and the outputs of the robot.

“We can see that in the near future there could be the potential to combine robotic milking with virtual fencing – that would be great for cow flow trafficking and pasture control.”

Pasture work-on

Moving into regen started with diversifying pastures. The Colemans increased the amount of regrassing and direct drilling, using diverse seed mixes with more than 20 different grasses, legumes and herbs.

“It’s taking lots of trial and error, but we are hopeful we can increase the persistence of the pastures through providing the species diversity, improved soil health and optimal grazing.”

Changing the fertiliser regime involved buying a Tow and Fert machine to be able to apply liquids, including fish hydrolysates, seaweed and humates.

Building the diversity in the plant life helps to feed and build the diversity in the soil life, in terms of microbes and fungi, and then they feed the plants, with it all happening through naturally occurring nutrient cycles and pathways, Darryl said.

Independently of the change, the Colemans had been doing worm counts on their pastures over the previous three years, particularly in the cropped areas, where they perceived the soil compaction problems were the worst.

Where there were counts of 15-18 worms in the spadeful on the dairy soils and only three on the ground historically used for cropping, the counts have doubled year-on-year, and are now more like 45-60 in the dairy soils and 15 in the more compacted soils.

Debbie said the worms are like the ‘big guy’ in the soil, and she thinks the farm is changing, finally seeing the urine patches receding and the farm looking a more even green. The theory is that the healthy soil microbiome provides all the required nutrients for the plant, eliminating the need for artificial or synthetic sources.

“Being organic, we cannot resort to simply putting on urea or other synthetic fertiliser or products to promote grass growth when required – the soil and the plants need to look after that themselves,” Debbie said.

Ever keen on monitoring progress, they are also testing to check that soil carbon is building and microbe levels are increasing, an indication that the soil is improving and is more able to release the nutrients that the plants need.

“We are utilising the soil biology to release nutrients for the pastures to thrive.”

Part of the regen process is extending the grazing round.

“Traditionally dairy farms sit at 20-22 days in spring and we are aiming for around 30 days and can get closer to 40 days later in the season with the robots, which allows a good feed wedge ahead of us for summer.”

Darryl and Debbie aim for high brix pastures through the longer rest period between grazings, which allows the grass to recover.

“The reason that the higher residuals and longer round lengths are a pillar of regen farming – we aim to leave higher mass residual, so the roots are not compromised and the plant persists better. Because the grass is allowed to go through a reproductive phase, the root mass is encouraged to grows and not reduced, there is more reseeding and it’s better for the soil biology because the plants are feeding the microbes.”

Darryl acknowledges palatability can be compromised in a straight ryegrass clover sward, but he says it is not as much of a problem in a diverse pasture because they have other species that are growing, maturing, seeding and dying down at different times of the year. So there is always something palatable and nutritious for the cows.

“We are beginning to see this now that we are three years into the diverse pastures – we are settling into a bit of a routine now, we have been through an adjustment phase.

“The ultimate goal is getting through to the healthy cows stage – where we have better in-calf rates, less mastitis, fewer downer cows and all those other things that seem to be an accepted part of modern dairy farming.”

Debbie said the ‘ambulance at the bottom of the cliff’ system was frustrating for her.

“Every year we seemed to cull high SCC cows, do the same amount of dry cow therapy and the next season we were doing the same – nothing changed.”

“I think this is where we are feeling encouraged by the regen and organic systems – we are not naive enough to think it can fix everything, but if we can halve the number of health- related issues – that would be a huge thing.”

Going to both conventional and organic discussion groups has given the couple an interesting insight into how practices and results vary across the two farming types.

“Whereas conventional guys might be happy with MT rates of 12-15%, the twice-a-day organic guys were reporting rates of around 8%.

“We have managed to bring ours down from around 12% to 8% – so we are pretty excited by that.”

While the Colemans said they have always been a low-intensity and low-cost operation, they hope the anecdotally predicted 10%-20% drop in production from going organic may not happen. Total annual milk production has not changed materially over the three-year transition period to date, and the reduction in cow health issues has resulted in fewer cows dropping out of the system.

Taking the grazing upright, not just horizontal

The transition to organics and the “closed” nature of their herd placed an increased focus on herd security, both physically and from a biosecurity perspective.

Darryl and Debbie decided to install a cattle stop on the main tanker and farm drive and double-fence the 18km perimeter around the farm to provide a biosecurity and organic “buffer zone”.

They are now planting these buffer zones with native shelter species, including pittosporum, flax, manuka and cabbage trees. They are also planting more internal shelter belts with natives and other fodder trees. Their plant nursery is an initiative to propagate and grow the large number of plants needed for the boundary buffer zones and the internal shelter belts, along with their 35ha regenerating bush area on their 100ha support land, which includes a series of gullies dropping to the Kiwitea stream. Debbie is interested in the medicinal properties and feed values of trees for cow health, acknowledging cows are browsers rather than strict grazers. Fodder trees include poplars and willows, and subdivisional planting will include trees able to be trimmed or direct-grazed for cow fodder. Tree lucerne, honeysuckle, alders, coprosma and pittoporums, kowhais and other soft-leafed trees, are all loved by the native birds and will also be able to be browsed by the cows, providing vertical grazing, shelter, potential cow health benefits and bird habitat.

The Team and the Numbers

The Colemans have a team of three full time staff (David Jensen, Paul Chapman and Maia Karl), along with Donna Chapman, who helps part time with calf rearing and whose role has recently been expanded to run the native plant nursery.

The farm is self-contained, with no additional feed or livestock purchased. The farm is also relatively self-contained operationally, with the team attending to all young stock rearing (including rearing their own bulls), attending to all their own silage making, pasture renewal, liquid fert applications, and all other farm maintenance (including lane maintenance and drainage).

The farm co-owns some of the required silage making, ground-working and regrassing equipment with Debbie’s brothers – Colin and Bruce Jensen – who are also dairy farmers in the Kimbolton area. The farm’s operating expenses (before depreciation, and debt servicing) for the last two seasons are $3.84/kg MS and $3.69/kg MS respectively. Darryl said some items of expenditure will reduce further once the farm exits the transition period and settles into a more routine pattern of costs.

In terms of environmental impact, the farm’s Purchased Nitrogen figures, as calculated by Fonterra, are negative 53kg N/ha in 2020/21, and negative 43kg N/ha in 2019/20. GHG emissions figures for these two years were 8065kg CO2e/ha and 7923kg CO2e/ha respectively.