Wearable lessons

Cow wearables can provide a treasure trove of information, and for South Canterbury farmer Tom Lambie, the technology has delivered some real gems that have led to big gains in productivity and performance.

Words Anne Lee, Photos Holly Lee.

The 785 cows (at peak milk) on Tom’s Meadowvale farm at Pleasant Point sport Tru-Test Datamars collars and have done so since 2022.

But it’s been the analysis of the data coming from the wearables by the farm’s veterinary service, followed by their action plans, as well as the farm team’s attention to detail in implementing the plans, that’s

seen the rapid progress.

The six-week in-calf rate has jumped from 68% in 2023–24 to 81% in 2024–25 and the not-in-calf rate after 78 days’ mating has plummeted from 19% to 8%.

In the first season with the collars, all had gone well. The collars had helped pick up cows on heat and find cows with health issues, Tom says.

“But in the second season it seemed that everything that could go wrong, did go wrong when it came to getting through calving and mating. We ended up with a 19% empty rate and that just about broke my heart – putting first lactation heifers on a truck to Southland because you can’t keep them in the herd – well you can imagine how that felt.

“I thought, right, we have these collars, let’s start making the most of the information they’re giving us.”

It was at a seminar on exactly that topic where Tom says he had the ‘aha’ kind of moment where so many of Meadowvale’s issues could be explained by the clues given by the data.

Contract milker Eric Tao-ey says the information gave insights that made sense and indications on where to look further. Having that deeper understanding helped get his whole team on board and everyone became very focused on implementing the plan to the letter.

Veterinarian Ryan Luckman from the Veterinary Centre, Waimate, worked with Tom and Eric on the plan and together they presented their experience, along with findings from other farms, at the South Island Dairy Event (SIDE) earlier this year.

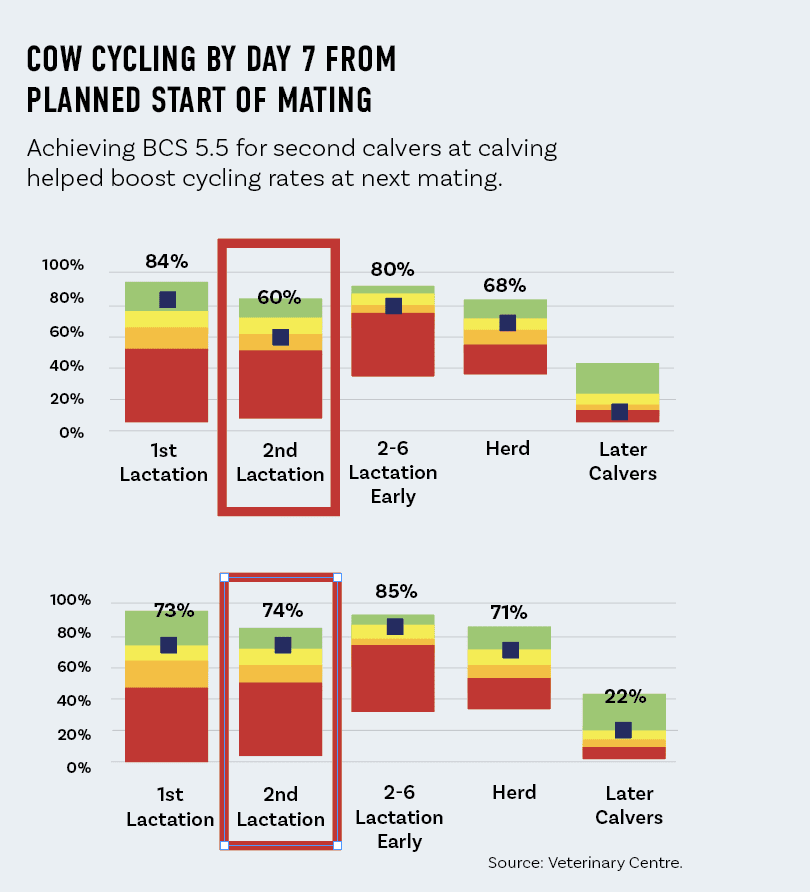

Ryan shared data showing pre-mating heat records where the information is broken out by age-group. If second-lactation cows have a lower percentage of animals cycling a month before planned start of mating compared with other age groups, body condition score (BCS) issues should be looked at.

“We ended up with a 19% empty rate and that just about broke my heart – putting first lactation heifers on a truck to Southland because you can’t keep them in the herd – well you can imagine how that felt.” – Tom Lambie, South Canterbury

“Everyone seems to know the importance of having first calvers at BCS 5.5 at calving, but for some reason they’re not putting the focus on second calvers, even though that’s a well-proven target too. They know it’s the aim, but they’re not monitoring it closely enough. The wearables’ data though is showing it can be quite a common problem.”

If heifers and second-lactation cows are run together as a separate herd, it can often be the second calvers doing the work to reach residuals, so monitoring their BCS, especially through autumn, is important.

If first lactation heifers aren’t managed separately in larger herds, they can often lose weight as rotation length increases because competition increases.

If you identify poorer second-lactation, pre-mating cycling as an issue, review how they are being managed in terms of grazing competition with other animals, pressure on achieving residuals and look ahead to what you can do for first-lactation heifers in autumn. Ensure they are dried off according to BCS and give them enough time and winter feed allocation to reach their target calving BCS of 5.5 for that second calving.

Transition feeding at calving

“There’s an abundance of research out there around transition which shows it’s one of the most critical periods in the whole season,” Ryan says. “It’s the period that goes from 10–14 days’ pre-calving to 14 days’ post-calving.”

Analysis from large data sets of wearables data has shown significant numbers of farmers have been underestimating feed allocations to springers (cows soon to calve).

“People heard the DairyNZ message about feeding springers 90% of energy requirement to help them switch to mobilising fat reserves, but when we looked at rumination data and put what they were feeding into an energy calculator, we found about 60% of our clients were only feeding 65% of required energy,” explains Ryan.

“We found about 60% of our clients were only feeding 65% of required energy.” Ryan Luckman, Veterinary Centre, Waimate

It’s also important to note that DairyNZ’s advice for cows that aren’t at target BCS is that they should be fed 100% of their energy requirements as springers.

If springer cows are being fed 10kg drymatter (DM)/cow/day as:

- 3kg DM grass @ 12 megajoules (MJ) metabolisable energy (ME) with 10% wastage,

- 4kg DM silage @ 11 MJME with 25% wastage,

- 3kg DM straw @ 6 MJME with 20% wastage,

they are likely only receiving 76 MJME when they need 103 MJME to be at 90%.

Eric says at Meadowvale they winter cows on up to 10kg DM/cow/day of fodder beet with cows transitioning back to grass on the support block adjacent to the dairy platform.

The successfully implemented plan last spring was to feed 8.5kg DM/cow/day of saved pasture and 2kg DM/cow maize silage and 2kg DM/cow straw for 10–14 days as springers.

Based on Ryan’s calculations, that provided cows with 92% of their energy requirement.

Based on Ryan’s calculations, that provided cows with 92% of their energy requirement.

Eric says cows are drafted into the springer mob initially on calving dates and then on udders. Heifers and mixed-age cows are run separately over that period.

Cows calve on the support block and move to the dairy platform for the first milking.

Once cows calve, the aim is to get rumination rates back up to their longer-term rates as quickly as possible – so day zero is critical, Ryan says.

“Rumination data can be used as a proxy for recovery even though it’s not a direct reflection of energy intakes but driven more by fibre levels.”

You can push rumination up by adding straw, but the lack of energy will see a crash in production and cow health. In first-round pastures, fibre levels will be relatively high and the main aim is to get enough of it and higher energy supplement into cows as possible.

Cows will often have a lack of appetite in the first 24–48 hours post-calving as they adjust to the birth process and changes in their bodies and metabolism.

Using cues such as shifting cows onto a new break by simply winding up the fence, feeding out silage or bringing in a feed trailer can kick-start their appetite on that first day.

“It’s a bit of a Pavlovian response, I think,” says Ryan. “When you wind up the fence, the first thing they do is get up and go and graze again. It’s the same response when you come in to feed out silage.

“What we’ve seen with the wearables data is rumination rates kick back up if you wind up that fence and offer a new break twice on that first day, and if you’re feeding a supplement, feed it at a separate time, that way it becomes a third new offering. You want three – whether that’s grass or two grass and one other.

“What we see with drop-in paddocks is that they can be the best grass paddocks you have, but for a lot of cows, unless they get those cues they just stand there and don’t eat.”

The other key factor in achieving recovery is not to push cows to graze below a residual of 1,800kg DM/ha.

“I think people see cows leaving grass behind on those first few days and think they’ve over-allocated, so they pull back what’s on offer and get into this negative energy balance. They keep winding the dial back and they’re just actually going further down this negative energy balance spiral. Allocate enough feed, get them behind a wire and drive their appetite by offering them multiple breaks.”

A drop in ruminations of 50–100/day is equivalent to 1–2kg DM/cow which in turn is equivalent to mobilising 700–750g of fat every day.

Meadowvale’s rumination data from the 2023–24 season showed a drop from 480–500 ruminations/day to 360–403/day on the day of calving with recovery coming at about day nine post-calving.

Last season they hit recovery by day two with second-lactation and mixed-age cows.

Eric says to achieve that they milked colostrum cows once-a-day (OAD) for the required eight milkings and then kept them on OAD for another 10 days.

Ryan sent them a daily rumination report and two weeks from the planned start of calving that report indicated which cows then moved to twice-a-day milking (TAD).

Colostrum cows were offered 12kg DM/cow of pasture, 1.3kg DM palm kernel, 2.3kg DM balage and 0.7kg DM/day of an in-shed mix that included dried distillers’ grain (DDG).

Total drymatter eaten, taking into account wastage, was about 14.5kg DM/day (16.3kg DM offered).

“Rumination data can be used as a proxy for recovery even though it’s not a direct reflection of energy intakes, but driven more by fibre levels.” – Ryan Luckman, Veterinary Centre, Waimate

In the previous season the Meadowvale team had used OAD, shifted cows on 12-hourly breaks and given them access to balage.

The major difference had been moving away from the ‘eye-ometer’ when it came to assessing pasture and trying to hit the 1,800kg DM/ha residual.

Instead, they were more focused on the Spring Rotation Planner and ensured cows were offered plenty of feed. Ryan says that from his experience, farms that use OAD over the colostrum period:

- Hold BCS much better

- Peak higher

- Hold the peak for longer

- See an overall increase in seasonal milk production.

Data from the Waimate practice showed all of the farms in the upper 50th percentile in terms of percentage of the herd cycling a month out from calving were OAD farms.

But there were OAD farms amongst the poorer performers which showed OAD on its own is not the golden ticket. Cows still have to be well fed and be managed through transition well.

DairyNZ research shows longer periods of OAD can have impacts on seasonal production, says Ryan.

At a herd level, OAD for six weeks from planned start of calving can result in 2–5% lower production on a kilogram of milksolids basis even if it is returned to TAD after the six-week period.

The production loss isn’t as great (1–2%) if the herd is on OAD for the first three weeks.

Effects on individual cows can be greater. OAD for six weeks post-calving can lead to a drop in production of 12% for some cows. If it’s for three weeks post-calving, the drop in individual cow production can be 7%.

The rules of thumb for OAD are to carry out the first milking within 12 hours of calving, with the next milking within a minimum of 24 hours.

If cows are first milked in the morning, the next milking should happen the following morning, but if the first milking is in the afternoon, the next milking can be up to 36 hours later – the morning of the third day – to bring it into line with the rest of the herd.

Moving to TAD should be based on a return to pre-calving rumination levels or, where no wearables are used, when the cow has gone from slack-sided (pear-shaped) back to a more rounded (apple) shape.

“We’re typically wanting rumination recovery levels to be back to normal as soon as possible, but we talk about 10 days’ ‘recovery’ as giving them extra ‘special care’ during a period where they’re less likely to eat and they’re recovering from calving,” Ryan says. “Most farms we work with use a 10-day minimum of OAD to cater for this and then use the rumination recovery to decide if any need to stay on OAD for longer.”

Eric says Ryan’s rumination report is the basis of the decision for a cow to move to TAD 10 days post the colostrum period, but he can override that decision if he’s not happy with other issues for the animal. He will also put a cow back into the OAD herd if required after a period in the TAD herd.

“You have to use your farmer’s eye and your own stock sense too,” he says.

He starts the TAD herd when he has 200 animals that have been given the all clear, which is about 20 August, so for a few very early calvers the OAD period can be almost four weeks.

Heat detection

A cow will typically ovulate and be ready for insemination within a 26-hour window from the time she displays peak heat activity. Farmers can tend to pick cows as soon as they see they’re on heat but the optimum time for mating can be slightly later. Wearables will often put up heat alerts later than farmers might pick them so that insemination takes place close to ovulation. Picking heats too late without wearables is mostly related to having just one heat detection aid, Ryan says.

“Plenty of cows will only set off one – either the tail paint or the scratchy or whatever you’re using. If you’re using two then you’re more likely to catch that heat coming on and time insemination correctly. The other time we see people inseminating too late is if they have two heat detection aids but they have put the tail paint on too thick.”

At Meadowvale, Eric was suspicious that despite the collars there were heat detection issues, and while he was fairly confident the collars were picking up heats, something wasn’t right.

“We tail-painted last mating and we found there were some errors with the EID reader talking to the drafting gate and we had to manually draft those cows out – that was about 70 cows. We found the collars were identifying silent heats – about 16 last mating, which was good.”

But Eric also found he could sometimes be picking cows, based on tail paint, a little too early.

“If I saw the cow was noticeably on heat – the paint was rubbed 50% – I would draft them off, but they would show up as a heat later that day.”

Ryan says that showed Eric was possibly picking cows right at the earliest point in the window.

“If the collar heat spike was rising when Eric checked the data on the cows he had picked on tail paint, we would get him to leave those cows till the next day so they would be in that ideal heat window,” he says.

Ensuring cows are in a positive energy balance through mating can have an influence on in-calf rates.

Protein percentage levels in milk can be an indicator of energy with increased energy intakes driving more protein through metabolic pathways.

“We do see a relationship too between protein percentages and six-week in-calf rate, although there are a lot of factors that impact that six-week in-calf rate so it’s not a given that you’ll get great mating performance just because of higher energy intakes,” says Ryan. “It’s a factor and an important one, but you have to get other things right too.

“If you’re not getting that one right though, it could be what’s dragging performance down. Focusing on pasture management at that time and ensuring cows are well fed so they are in a positive energy balance situation is very important.

“I’m a big fan of maths and real numbers rather than gut feel with this. Know the energy values of what you’re feeding and what your cows need and make sure you’re meeting that need.”

Meadowvale’s attention to detail when it came to pasture management and allocation of feed including supplement through the 2024–25 spring

is likely behind a rise in milk protein percentage from mid-October and through mating, Ryan suggests.

In the previous season, protein percentage was lower at the planned start of mating and then dropped before it started to climb again in mid-November.

“We were grazing to a 1,600kg DM/ha residual and followed our grazing management plan closely, monitoring residuals and pre-grazing covers daily and monitoring the cows through the day.

“You have to be diligent – go out and check the cows,” advises Eric. “We do two breaks in 24 hours with 40% allocated during the day and 60% for the night so we can adjust and check during the day.”

Other technologies for improved mating

Short gestation semen

The use of short gestation semen from week five of mating can make significant improvements to the six-week calving pattern even though the six-week in-calf rate is not reaching target. An actual six-week in-calf rate of 67% can become a six-week calving pattern that equates to a six-week in-calf rate of 75% by shortening gestation length and having cows calve earlier, into the six-week from planned start of calving window.

Phantom scanning

Identifying cows who have been mated, not returned to heat but are not in-calf can help reduce your overall not-in-calf rate by about 1.5%. Scan 10 days before the end of mating to pick up phantom cows and give enough time to inseminate.

Ryan’s tips on Wearables

Rumination data can show how well feed allocations are being managed, particularly for those using flexible milking intervals such as 16-hour milking. But be sure to interrogate the data closely.

“We had one farmer who had ruminations dropping on the day they milked twice-a-day (TAD), but when we looked at the data more closely the drop was happening about midnight on the night after they were milked once-a-day (OAD) ,” Ryan says. “It was the OAD allocation that was wrong and where they were under-feeding. It’s a common problem.”

To mitigate the risk of under-feeding on those days:

Continue offering two breaks as you would for the TAD milking days – so an afternoon break as usual.

Allocate total feed over a 48-hour period and split the hectares fed according to the interval between milkings. If cows are milked at 10am on the OAD milking day and 5am and 3pm of the TAD milking day, the interval between 10am and 5am is 19 hours. The break size will be 19/48 = 40% of the total hectares fed over the two-day period.