Sheryl Haitana

New Zealand produces a fraction of the world’s greenhouse gases and our

dairy industry is 30-50% more carbon efficient than the rest of the world.

The argument to not be concerned by NZ emissions because we are too

little to make a difference to a global issue, particularly when the world’s

leading emission culprits are dragging their feet to address climate change, does not resonate with Australian climate scientist Will Steffen, however.

“We live in collective societies, we all have to do our part whether it’s big or small.”

There is a real opportunity for NZ to lead the world in this space and capture the market, because dairy is not going to disappear, he says.

“The dairy sector is regarded as somewhat of a villain now, but it has the

potential to make some really quick gains.”

Steffen spoke at the Bold Steps Conference at Auckland in December and painted a bleak picture of where he sees the world heading.

The world is heating up and is heading quickly towards tipping points where the world will spiral out of our control, he says.

Since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2016, emissions have continued to rise and the world is getting closer to the tipping point of no return.

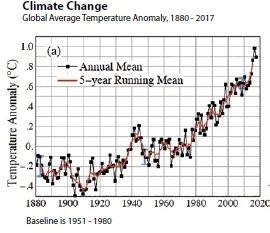

The global average temperature from 1880 to the present, is going up sharply, 100 times faster than we can see, he says.

“The globe is now passing 1.1 degrees and we have locked in at least 1.3 or 1.4 degrees so it looks like we can’t reach the lower end of the Paris Agreement target.”

When you compare the increase in temperature of the last 120 years to 2000 years of natural variability the earth has never seen these temperatures before – unless there was a meteorite strike or some planetary calamity, he says.

“This is way outside the norm of what the earth systems experienced. We are heading to between a three and four degree temperature increase.”

Even at 2C there is a big risk of destroyed ecosystems and extreme weather events and the world is already seeing instability at 1.1C.

Most scientists presume we can reverse emissions anywhere along the way, but that’s not how a complex system works. There will be tipping points, Steffen says.

“Ecosystems are collapsing and biologists tell us we are at the beginning of a mass extinction.”

The Amazon has experienced three years of drought in the last 10 years, each one being a one-in-100-year event and it’s losing carbon. The Greenland Ice Sheet and the artic summer sea ice is melting and dumping fresh water on the North Atlantic Ocean, slowing the Atlantic circulation by about 15%.

That slowing of circulation means there is less rainfall for the Amazon and as the Amazon flips to a grassland savannah, it could lock in a positive El Nino, which affects Australia and NZ.

“All of this is climate change, we’re seeing it now, it is on the ground and indeed it is an emergency.”

These tipping points are starting to become active and we are already committed to losing some of these eco systems, he says.

For example, the Great Barrier Reef is dead and the other half has a death sentence, it will be gone by 1.4C or 1.5C.

The biggest risk is that the earth system moves out of control, past the tipping points, and becomes a hot earth.

“This is not a future we want to go to.”

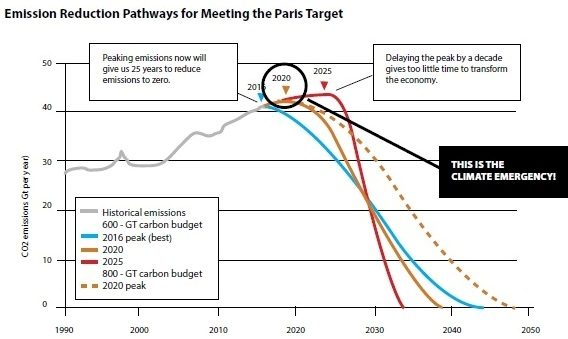

If the globe can peak emissions at 2020 it will have a couple of decades to bring down global emissions, but waiting five years to 2025 years it will become impossible, he says.

“This is why we face an emergency we can’t even wait five years to start emissions on that downward trajectory.

“This is why it is important countries start legislating, that you actually have to get emissions out by 2045 to 2050. There are half a dozen countries doing that, New Zealand is one of them.

“Unfortunately, the big emitters, aren’t even close yet to doing that.”

The climate deniers’ argument is the temperatures we are witnessing and the effects on our eco systems is part of a normal cycle, which is “bullshit”, Steffen says.

“There is absolutely no doubt. It’s physics 101 that when you put greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere they trap heat.”

This is why students like Greta Thunberg have it right. Civilisation is facing a climate emergency, he says.

“They (the younger generation) understand their future is at risk and that we have failed to understand – including many in my own science community.”

To create change and bring down emissions is a challenge, but

humans can react fast to global issues, they’ve shown that in movements like after the Second World War, Steffen says.

“We are capable of doing that. We have to act now. It is possible, but we have to move fast and we don’t have any time to lose.

“We have to rethink the system, we have to change our government systems, our economic system.”

FUTURE FOR NZ DAIRY

The New Zealand dairy industry has real potential to be a world leader in reducing greenhouse emissions, Steffen says.

“NZ is in a good position. NZ has some really good scientists. If we can crack the methane question in agriculture that is huge step forward.”

Methane has a half-life in the atmosphere of about 12 years, but has a global warming effect 25 times greater than carbon dioxide. If NZ dairy farmers can focus on reducing methane the industry and the country will make huge wins.

“The interesting thing there is if methane emissions can be brought down by whatever technique, you have a really quick effect on the climate. It gives you a quick bang.”

Globally agriculture is the biggest emissions sector after energy and transport. Getting methane emissions down fast in agriculture gives NZ space on its other emissions such as CO2, he says.

“If you can make quick gains on methane in agriculture it allows other parts of the NZ economy space which may be longerterm infrastructure change.

Innovation and technology will play a key role in solving the methane problem.

If there is a magic bullet for methane in dairy cattle, whether it is seaweed, or vaccinations, NZ has some really good scientists that might be able to crack it, he says.

Another good way to get emissions down is to go to more complex agricultural systems that mimic ecosystems, he says.

“If we have plants and animals together it’s more complex, it’s not a monoculture, and you manage it and harvest it in the right way you can be building back some of the soil carbon, which is being depleted through intensive agriculture.”

Carbon pricing or pollution pricing can steer agriculture to more holistic and more complex systems.

Farmers might see the Zero Carbon Act as a threat to agriculture but they need to flip the coin to have a different point of view.

“If you unleash innovation there are massive opportunities.

“We have to get over that hump of resisting change. The question is how fast and what direction can we change.”

Planting pine trees to offset carbon emission is not an optimal long-term option, and Steffen does not support offset schemes used by big corporates.

“I’m very much against offsets. I never buy offsets on an air ticket.

“I would pay an extra fee if it was for research to develop bio aviation fuel or some other types of aviation because that is where the future is. Whether it’s algae-based or using waste.”

He is also more in favour of regulation than pricing.

“It puts bounds on the economic system that you simply cannot do this – this is your limit. You do not make a profit if you trash the planet.

“The problem with using pricing is someone will always find a way to weasel out of the system. They earn enough money and they just pay the price.”

The whole incentive for profit must change to make companies more accountable, he says.

Rather than planting pine trees to offset emissions, NZ should plant native trees that have a better long-term outcome for the environment.

“Go back to more natural native complex eco systems, they’re more resilient, they give you biodiversity, they store more carbon, they may take longer to grow, but it’s the long-term outcome you want.”

Aviation will be one of the tougher nuts to crack. That’s why it’s important to get emissions out of the easy stuff first so countries have space for aviation travel.

China has the model, connecting 211 cities with high speed renewable rail. There is no reason people in China or Europe should fly between cities within 1000km when they can go by rail.

In fact, China may hold the key to getting global emissions down, Steffen says.

The United States and Australia are big problems because they are not tracking in line with the Paris Agreement. China is hard to pick because they are doing some really great things but still have a lot of coal mines, he says.

“China has the potential to be the game-saver actually – their size, their technology, their impact on developing countries. They

could be the big gorilla that tips the global system.”

could be the big gorilla that tips the global system.”