Adapting to compost

Composting barns allowed Murray and Gaye Coates to quit winter crops and reduce soil damage, potential phosphate loss from mud and nitrogen leaching on their West Coast farm. By Anne Hardie.

Murray and Gaye Coates are learning how to make compost and are discovering the process is far more forgiving than they feared. Their key message to other farmers new to composting barns, is don’t panic when there are hiccups in the system.

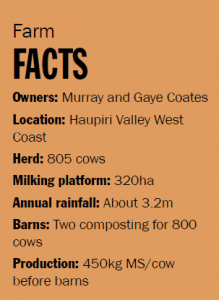

The couple farm 805 crossbred cows in the Haupiri Valley at the base of the West Coast’s mountain backdrop where 3.2-metres of rain falls annually on their 320-hectare milking platform. In the past they had a 400-cow feedpad with the necessary consent, but they were not satisfied. They needed more space for their 805-cow herd and wet springs could result in significant pasture damage which was stressful.

Environmentally, the composting barns ticked the boxes by quitting winter crops and reducing soil damage, reducing potential phosphate loss from mud and less nitrogen leaching.

They saw how successful composting barns were working in Taranaki which also had high rainfall and after a couple of years of talking with farmers, consultants and anyone with any knowledge on the barns, they took the plunge. They now have two composting ‘mootels’ that each cater for 400 cows.

Aztec Buildings built the barns along a design created by Headlands Consultancy specifically for the climate and needs of the Haupiri Valley farm. Each shed is 80m in length by 45m wide which includes two 5m-wide feed lanes inside, under cover. That gives each cow 6.5 square metres of space which works well, though the cows are getting bigger because they have better utilisation of feed.

The sheds were built in time for the cows to winter in them and they remained in them until they had calved. The final touches to the project have continued through to spring and tweaks are ongoing. It is all part of the continuing improvements on the farm to try and future-proof it, environmentally and economically.

Taking a step back, Murray and Gaye bought half of his family’s farm at the end of the 1990s and ran sheep, beef and deer for years. Then, they joined the movement to dairying by converting the farm in 2008.

“Cows got expensive to buy, but by that stage we were at the point of no return,” Murray says. “The first year we started milking we had the clawback from Westland.”

They borrowed more money to clear more land and increased cow numbers to 590 on a 270ha milking platform. Today the farm has a total area of 420ha and uses 320ha as a milking platform, with the remainder in bush. The bulk of the farm is river silt and the high rainfall is delivered in often big events. This spring they had 130mm of rain one night, but the cows were in the shed on their wood chips which will slowly turn to compost, while the pasture and soils were protected.

“It’s the relief,” Murray says. “It’s hard to put a figure on that.”

Their barns are a steel and pole design because the wind can really rip down the valley from the nearby mountain pass. Between wind and high rainfall, they added a few extras to try and keep them intact and keep the rain out. The strengthened ventilation running the length of the roof ridges is open permanently but is built with a good overlap so rain cannot get inside. As Murray points out, rain can run uphill with wind behind it and the overlap needed to cater for that.

On a hot day, the ventilation is designed to create a draft to cool the barns, as do the dimensions. The barns’ height begins at 4.5m and climbs to 11.8m at their apex, with an 18-degree pitch roof.

Airflow is crucial for successful compost and likewise, keeping excess moisture out. Through winter, the barns did not have the gables attached at each end which let rain drive about 10m inside and wet compost. Murray says water “is the killer of compost” and soil probes showed some of the woodchip was sitting about 20C in the wet areas and 40C in other areas.

“We were panicking because we thought it had to be 60 degrees,” Murray says. “We learnt the biggest thing is don’t panic. Compost is more forgiving than people believe.”

Gaye says they overcame the wet problem by tilling, tilling and more tilling to keep the composting process working.

“I think you have to go into this with the realisation of learning through experimentation and perfection won’t always be attained first up,” she says.

All going well, they hope they will not have to replace the compost bedding for several years. One of the farmers they spoke to in Taranaki has not replaced their compost in seven years. Eventually, the Coates plan to spread the composted bedding over the farm.

Murray and Gaye are keen to point out that the options they have chosen are to suit their own farm and system and other farmers may do their research and choose different options.

Their farm consultant at the time, George Reveley, challenged them every step of the way to think about how they could create a multi-purpose and flexible space for their farm and weather conditions. He stressed it needed to be safe, practical and pleasant for cows and people.

“He wanted us to think about how a shelter could work in with our existing farming system, rather than change our system to fit a barn,” Gaye says.

That meant thinking about how the space could and would be used at different times, like mating and calving. Also, the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of various shelter options for seasonal and climatic variances.

“For us, composting barns seemed to be weighted more to the strengths and opportunities presented by our existing farming system within the context of our climate and environment.”

Keeping the water out

Work on their barns continued through to spring and they now have the gables in place and mesh on the sides to stop rain driving inside. The eight water troughs are inside the barns, so cows do not walk out into rain for a drink and bring that moisture back on to the compost.

The feed lanes are inside which is more expensive, but again it means less water coming into the sheds and the dry feed is more palatable, resulting in less wastage. They polished the concrete after viewing a shed where the cows had ulcers on their tongues from rougher concrete and consequently were not eating their feed well.

The basis for the compost is $150,000 of woodchips that gobbles up dung, while ideally the heat of the compost evaporates the urine. Ninety percent of the 805-cow herd calved in the barns and the placentas just disappeared into the compost, even before it was tilled.

A Rata subsoiler has been converted to do that job. Wings have been added to the points to help turn the compost over. When the cows were housed full-time through winter, the compost was tilled every day, aerating and mixing the compost to a depth of about 500mm. Murray says the frame of the machine holds it back from tilling even deeper and it ends up levelling the surface. Further adaptions may be necessary to achieve a greater depth. When the cows are not in the shed, they till the compost twice a week.

As well as tilling, they use a crumbler behind a chisel plough to break up any clods in the compost. Initially they tried the chisel plough for tilling, but it did not get deep enough into the wood chips. The goal is to get everything on to one machine, but that is a work in progress.

In other adaptations, the tyre pusher that pushes feed up for the cows and keeps the area clean, now has two spinning tyres which works more effectively.

Among the unexpected costs, a telehandler is now used to load the BvL feed mixer wagon to make it safer lifting feed to the height of the wagon. They add round bales of balage or silage into the mixer, a bit of straw and can add palm kernel if needed.

Through winter they fed out the equivalent of 9kg/cow/day in the barns, though they fed them every second day, which meant 18kg per cow for two days.

“It’s a bit like Christmas and then you have the pickings on Boxing Day,” Murray says.

Another extra was an older second-hand tractor to replace the tractor now dedicated to the mixing wagon. They may need to build another shed at some stage to cover woodchip waiting to be used. Woodchip has to be dry from the beginning and the West Coast climate is a risk for a large pile of dry woodchip.

The extras have added costs to the barns, but the barns have already delivered improved returns. For the first time, Murray and Gaye milked cows to the last tanker pick up on June 13 because they had the cows in the barns and did not have to worry about pasture or winter crops. That gave them another 8000kg milksolids (MS) which was “pretty valuable” to them. Their goal is to milk through to mid-June each year which will lift their production beyond the 450kg MS per cow they have been achieving.

On the cost side, the actual barns cost in round figures $900,000 each. Adding on the concrete feed areas and more concrete leading into the barns, plus machinery and woodchip, the total spend was about $3250 per cow. Murray says they were fortunate to have a set price from the beginning as building materials and associated costs have risen exponentially over the building period.

They had to change banks to get the project over the line and found Westpac very supportive of the project.

Financially, the barns stacked up against the status quo and the winter crops of swede were becoming a difficult option with environmental regulations.

The composting barns are a massive learning curve because it is not just about compost and feeding the cows differently – there is also the effect that has on pasture management. Murray and Gaye say it will probably take a few years to work out the right residuals when they dry the cows off.

By June 13 this year, they had more than 2000kg DM/ha of cover which was too high and Murray says quality was not great. To deal with that, they kept beef stock longer than they intended. The cows calved in the barns so that again altered pasture covers at the beginning of the season.

In future, he says a residual of 1800 to 1900 may be the target going into winter and it will take time and a variation of seasons to work out how to manage their pasture on the shoulders. That will affect other aspects such as calving too.

Next winter, they will buy two-year-old steers in winter for pasture management, run them behind the cows as a topping tool and sell them to the works before Christmas. Murray describes it as “hoof and tooth” which is cheaper than diesel. They already keep beef calves including about 80 Friesian-type bulls and 40 Hereford-cross bulls which they sell weaned at 100kg.

They have used short-gestation Hereford straws in the past, but found the calves too small for animals that were being grown for meat. Now they use Hereford bulls to go over the last of the cows at mating.

For the cows, the focus will be feeding them well through autumn to meet residual targets. Lighter cows will head into the sheds as soon as they are dried off and the bulk of the herd heading in on June 13 for winter.

The cows calve from August 1 and through the season they will get topped up with feed in the barns if their paddock does not supply their quota. Murray says they are still grass harvesters and will be using grass supplements for the bulk of feed in the barns. They will be making between 2500 and 3000 round bales of balage or silage equivalent.

From calving, the herd will be milked twice a day which will drop to 3in2 as soon as artificial insemination (AI) finishes. This will be the fifth season they have used that milking regime and it has worked well.

The valley reaches temperatures in the 30s during summer and Murray says the cows used to sometimes be panting in the yard. They were also getting high empty rates, so they changed their milking times. Through 3in2 they milk 4am and 5.30pm one day and then 10.30am the next day.

This season, the cows will head to the barn when the heat cranks up. Murray says they will begin monitoring the heat and identify a trigger point to bring them out of the heat. It may be 25C, or it may be less.

Once inside, the cows can carry on eating in the cool of the barn.

AfiCollars on the cows monitor heat stress, as well as ruminations and head movement which will help determine the right time to head to the barns. They connect with the Afi Herd Management System in the dairy which determines how much feed is given to each cow at milking. A mix of meal, wheat, molasses and mineral pellets is fed to each cow according to the information from the collars.

It is all part of Murray and Gaye’s strategy to weigh, measure and calculate everything on the farm. Their latest tractor has self-steering and combined with GPS on the spreader, enables them to apply everything accurately in their goal to be precision farmers.

The composting barns are part of that strategy. They know what the cows are eating and can minimise wastage. At this stage they can only estimate how much nitrogen the compost captures.

Down the track, Murray and Gaye say it is quite possible that research may come up with a means of using the barn to monitor, manipulate and/or minimise methane.