Agritrade: FE risks grow with El Nino

The window for facial eczema is often misconstrued. With El Nino conditions forecast to last well into the end of autumn this year, hot dry conditions followed by warm rain, could see increases in fungal growth and spore production be a risk over an extended period.

A lot of farmers traditionally start facial eczema prevention in early January and aim for a 90 day cover, however, the risk of exposure can be wider than that, Agritrade Sales Manager Paul Senior says.

A lot of farmers traditionally start facial eczema prevention in early January and aim for a 90 day cover, however, the risk of exposure can be wider than that, Agritrade Sales Manager Paul Senior says.

Even in a “normal” season, the window can start to creak open well before Christmas and not completely shut until the end of Autumn.

The fungus (Pithomyces chartarum) produces spores when grass minimum temperatures are above 12C for two or three nights and humidity is high. The spores grow quickly in dead or dying grass litter typically found in the base of pasture during summer and autumn months when conditions are more favourable for spore development.

However, a slow build-up of spores and continual exposure over a period of time will also result in similar risk levels, with continuous exposure to spore counts as low as 20,000 causing as much damage as short spikes, Paul says.

Even at low spore counts, milk yield can still be impacted – (see Agritrade trial results).

Like many factors in farming, it is about finding the cost benefit balance; ensuring you are treating your animals effectively at the right time, and not treating them when it’s not needed.

Measuring and using data is the best way to be on top of when facial eczema is an issue onfarm, he says.

A number of tools are available to farmers around spore count testing. Farmers have access to regional data with spore count monitoring and can test their own individual paddocks.

The problem is every individual farm is different and every individual paddock is different.

Farmers are also time poor and daily dosing can become a challenge and be inconsistent. The time when the risk for facial eczema is most present is usually when farmers are thinking about a summer holiday or staff are on holiday after a busy season of calving and mating, Paul says.

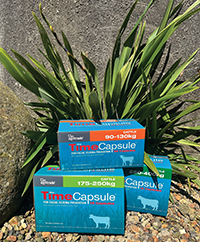

“It comes down to consistency. A bolus such as the New Zealand-made Time Capsule® dissolves over a four-week period to give dairy cattle a consistent dose of zinc oxide daily to protect the animal from facial eczema.”

It gives farmers the comfort of knowing those animals are protected no matter what paddock they are going into, no matter what the weather is doing or what the temperature and humidity level is.

When it comes to young stock, in particular, which are often grazed off the milking platform and are monitored less, treating them with an intraruminal bolus is still the most effective option, he says.

When it comes to young stock, in particular, which are often grazed off the milking platform and are monitored less, treating them with an intraruminal bolus is still the most effective option, he says.

Overall, there is still a place for more education around facial eczema, Paul says. There remains a lot of misconceptions around what facial eczema actually is, how it presents itself and what the biggest risk factors are.

For example a lot of people believe once there has been a frost, all fungus spores are dead and there is no longer any risk. However, temperatures can spike back quickly and spores can still be present and causing issues.

Another common assumption is significant rain will decrease the spore numbers present, which is true in the short term, but again they can rise again quickly if conditions are right.

Education is key to breaking through these misconceptions so farmers have a clearer picture and have the best information to make decisions with, Paul says.

One of the biggest educational sticking points is still what the true health impacts of facial eczema are in what are often hidden symptoms.

Some farmers still perceive they don’t have facial eczema issues until they see the skin peeling off an animal, for example, he says.

Or some still believe black cows don’t suffer from facial eczema liver damage because they may not exhibit pigmentation and skin peeling.

“Would we even call it facial eczema today? Because the reality is the real issue is the liver damage.

“I have had farmers tell me they’ve separated cows that have peeling skin so the other cows don’t ‘catch’ facial eczema.

“That tells me we need to do a better job of educating people about what facial eczema is.”

Cows can recover from peeling skin, but badly damaged liver tissue will not regenerate and will have a big impact on the milk in the vat and that cows’ performance in the herd going forward.

The hidden subclinical issue of liver damage can cause up to 50% decrease in milk production. It is estimated that for every clinical case there will be 10 cows with subclinical facial eczema (DairyNZ).