Applying science to suckling

Keeping calves with mum until weaning is part of a study of alternative rearing systems. By Anne Lee.

Keeping dairy calves with their mums until weaning conjures up idyllic, chocolate box images for some but for commercial dairy farmers the concept is more likely to throw up numerous logistical challenges.

How do you manage milking, what happens to cow milk yields and what effect does the system have on cows and calves when that inevitable separation day comes?

A study at Lincoln University’s Ashley Dene Research and Development Station is looking at a suckling calf rearing system, where cows and calves are kept together until weaning.

It’s part of a larger study investigating short and long-term effects of different milk allocations with two other groups of calves reared more conventionally, separated from their mothers soon after birth and then fed either a standard 6 litres/day of milk or a high allocation of 9 to 12 litres/day.

Dr Racheal Bryant is leading the study and says initially the interest was on comparing the high and standard milk offerings because overseas research had found heifer calves reared on the higher allocations were more likely to have faster growth rates and go on to produce more milk once they joined the milking herd.

Not a lot of work has been done to date on this in New Zealand pasture-based systems.

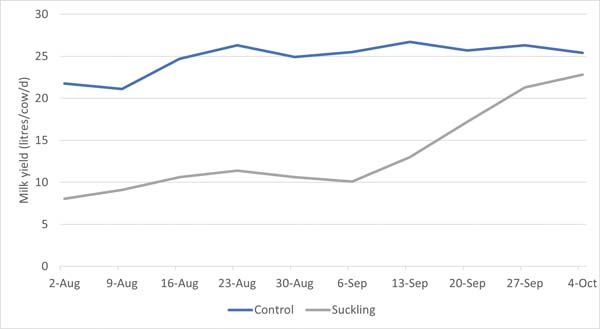

Racheal says by comparing the suckling cow milk yields with similar cows in a conventional system at the research dairy farm, her team is able to estimate how much milk the suckling calves are consuming each day.

It turns out they’re likely to be drinking a lot more than their artificially reared peers who struggle to consistently drink 9 litres/calf/day, and could be averaging 12l/calf/day.

Racheal says they decided to include a suckling group in their study to gather some hard data on the practice given the increasing pressure conventional farm systems are coming under from some groups.

“Consumers are taking more and more interest in how their food is produced and their perceptions are having a real influence on farm production systems – just look at the egg industry in New Zealand and the effect moving away from caged eggs has had on egg supply and price.

“We wanted to build our knowledge on just what the effects might be on calf growth rates and their subsequent performance in the herd – do they reach weaning weights earlier and what effects does all of that have on their own milk yields once they enter the herd.”

Developing a better understanding of how to manage cows and calves together till weaning and looking at the productivity effects of such a system is important because it not only gives farmers a heads up on what to expect, it also allows scientifically backed facts to be brought into a very emotive issue.

To gather the data, Racheal and her team have looked at the three groups of calves over three seasons – this is the third season.

Each year they’ve tweaked the systems slightly – adding more milk to the high milk allowance group and changing the way calves and cows are managed over the time they’re together in the suckling group. The calves in the artificially reared groups were on automatic feeders with a maximum daily intake set depending on which group they were in.

The feeders recorded when the calves drank and how much. If they reached their allocation for the day the machine prevented them from getting any more until the next period starts.

All cows were herd tested regularly to compare milk composition and milk quality as well as udder health so that comparisons could be made between cows with suckling calves and the dams of the artificially reared calves.

Blood tests were taken from calves to look at passive immunity transfer to see if there were any differences between the artificial rearing system and the suckling system.

All the calves in the artificial rearing system received first milk gold colostrum within 24 hours of birth but there was no intervention in the suckling system except that only cows with calves observed as bonded and suckling soon after birth were included in the study group.

What they’ve found

Results from this final year are still being collated but are showing similar trends to previous years.

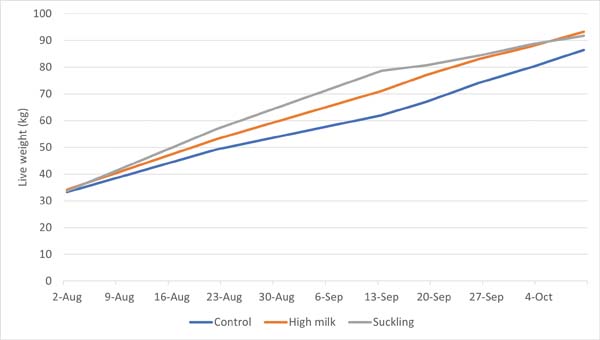

In the first two years it was apparent that the suckling calves had higher growth rates, weaned earlier on average and at weaning were consistently heavier than calves reared artificially.

“They were at least 10kg heavier from six weeks on.

“It would probably mean the difference between weaning at 10 weeks compared with 12 weeks if we’d been weaning on weight rather than time.

“In the first year we had a lot of the suckling calves close to 80kg by six weeks,” she says.

The suckling calves maintained their weight advantage after weaning with growth rates becoming similar between the different groups.

However, the suckling calves and high milk allocation calves dropped in growth rate compared to the control calves during the transition off milk.

This was expected based on previous research showing that higher milk feeding results in lower solid feed intake and slower rumen development, she says.

Racheal says the calves on the higher milk allocation in the artificial system didn’t do as well as they’d expected in terms of growth rates which was likely due to the fact they didn’t drink that full allocation, instead consuming about 7 litres/calf/day on average.

This year the control calves consumed 5.8 litres/day and the high allocation calves averaged 9.1 litres/day.

This has resulted in average growth rates of 0.68, 0.90 and 1.07kg/calf/day for the control, high allocation and suckling calves in their first six weeks.

“We think the suckling calves averaged up to 12 litres/calf/day, based on their growth rates of over 1kg gain/day and energy requirements to meet that growth.

“Suckling alters the milk let down and milk composition of the dams so it’s not a straightforward comparison with the milk yield of control cows to estimate calf milk intake” Racheal says.

In both of the first two seasons, while suckling their calves, the cows have produced about 10-12 litres of milk per day less at the farm dairy than the cows whose calves were removed and artificially reared.

Once their calves were removed, at six weeks in the first season and 10 weeks in the second season, the difference in milk yield between cows disappeared.

Milk harvested at milking in the farm dairy from the suckling cows had lower fat content than the other cows, but there was no significant difference in protein levels.

Although there were inconsistent results when it came to mastitis and milk quality effects, it was apparent that towards the end of the suckling period cows had more teat end damage.

“Colostrum intake for transfer of passive immunity was variable and although there were no statistical differences between groups for passive immunity, several calves failed transfer of passive immunity, particularly in the first year.

“Cows and calves appeared to have bonded, but that didn’t mean that calves had suckled sufficient colostrum within the necessary 8-12 hour window to absorb IgG (immunoglobulin).”

The suckling calves drank a lot more milk and Racheal says nutritional scouring was evident although health wise this didn’t seem to be affecting the calves adversely.

Thanks to mums’ grooming, calf hygiene in the suckling group is taken care of. They had access to calf muesli and hay in the movable shelter in the paddock. Racheal says beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) levels in blood tests can be an indicator of rumen development and while the suckling calves’ dung might have indicated otherwise, the tests showed they had similar or better blood BHB levels than the artificially reared calves.

All the calves are being carried through as replacements and calves from the first year have just entered milking herds at the research farm.

“We’re following those animals through to look at their reproductive performance as well as their milk production and animal health,” Racheal says.

Practicalities and distress levels

You’ll hear them before you see them.

The cows in the suckling group come bellowing into the paddock as they’re reunited with their calves and will do the same as they leave their calves.

Paige Beckett is the research technician managing the day-to-day activities of the study.

She says shifting cows to separate them during the day can take effort to start with as cows want to return to the paddock.

“It takes them a few days to get used to the process and you’ll get some that are always more difficult than the others.”

“Generally, though they do get used to it, although we’ve had to make sure they were far enough away they couldn’t see their calves – especially last year when we separated them at nights.

“It’s the cows that are more upset – the calves very quickly are pretty unperturbed.”

The research area where the calves remain has a calf-proof lane and boundary fence along the side the cows go out and calves are happy to graze, lie down in the grass or sit in the shelter.

When the cows return, it’s the cows who do the calling and the calves wander amongst them to find mum and get a drink.

Paige says there haven’t been any incidences of calves being hurt by the cows or cows getting overly aggressive, but her extensive experience in animal handling means she’s always alert to the possibility. Separating the calves at six weeks and rearing them through till 10 weeks had its challenges for people and animals. Cows were upset at being separated, some bellowing for their calves for a couple of days.

The calves coped a lot better but were big and difficult to train onto a calf feeder at that age.

Health and safety in handling cows and calves or training older calves would be a factor to consider.

Letting mum do the feeding right through to weaning is definitely preferable, she says.

But separating them for periods – either day or night – and extending that separation period closer to weaning may help with the cow distress. This season, adopting a partial contact system, where the cows and calves are separated every day, will be monitored to see if there is less of an impact on milk yield and separation distress.

What they’ve done so far

2021 spring

Suckling group

- 15 cows and heifer calves

- Full contact for six weeks then separated on September 27 at about six weeks old.

- From six weeks to 10 weeks old reared artificially on calfateria. Calves were >60kg so it was a two-person job to teach them to feed.

- Cows milked once-a-day (OAD) for six weeks with calves able to come to the farm dairy.

- Cows milked twice-a-day (TAD) from when calves separated at six weeks.

- Calves have access to meal, silage and pasture from birth.

- Calves have access to a moveable shelter.

Artificial rearing

- 30 heifer calves separated soon after birth, fed colostrum and reared on automatic feeder with either 6l/calf/day or 8l/calf/day (high allocation) of whole milk on automatic feeders (15 calves per group).

- Access to meal and silage from birth and pasture from two weeks old.

2022 spring

Suckling group

- 12 cows and heifer calves

- Full contact for six weeks then night separation where they can see and touch but not feed, until 10 weeks old.

- Weaned at 10 weeks, October 10.

- Cows milked OAD when with calves.

- Cows milked TAD from six weeks when calves separated at night.

- Calves have access to meal, silage and pasture from birth.

Artificial rearing

- 24 calves separated at birth fed colostrum and reared on automatic feeder.

- High allowance group allowance increased to 9l/calf/day with control allowance remaining at 6l/calf/day (12 calves per group).

- Access to meal and silage from birth and pasture from two weeks old.

2023 spring

Artificial rearing

- 30 calves separated at birth, fed colostrum and reared on automatic feeder.

- High allowance group allowance increased to ad lib (max of 12l/calf/day) with control allowance remaining at 6l/calf/day (15 calves per group).

- Both groups on 80-day milk feeding plan on automatic feeder.

- Access to meal and silage from birth and pasture from two weeks old.

- All calves were weighed weekly from six weeks old and transitioned off milk if body weight greater than 76kg with target minimum weaning weight of 80kg.

Suckling group

- 15 cows and heifer calves

- Partial separation for the first six weeks, with calves separated from mothers at 8.30am with mothers given fresh pasture break.

- Cows milked OAD about 3pm and returned to calves.

- From six weeks, calves fed OAD from their mother an hour before the afternoon milking

- Cows milked TAD from six weeks

- Calves have access to meal, silage and pasture from birth.