Clock ticking on agrichemicals

European Union rules on a range of agrichemicals used in New Zealand farming are set to expire by 2030. By Elaine Fisher.

New Zealand farmers and growers are running out of tools to manage pests and diseases and urgency is needed in the registration of new, greener options, Animal and Plant Health chief executive Mark Ross says.

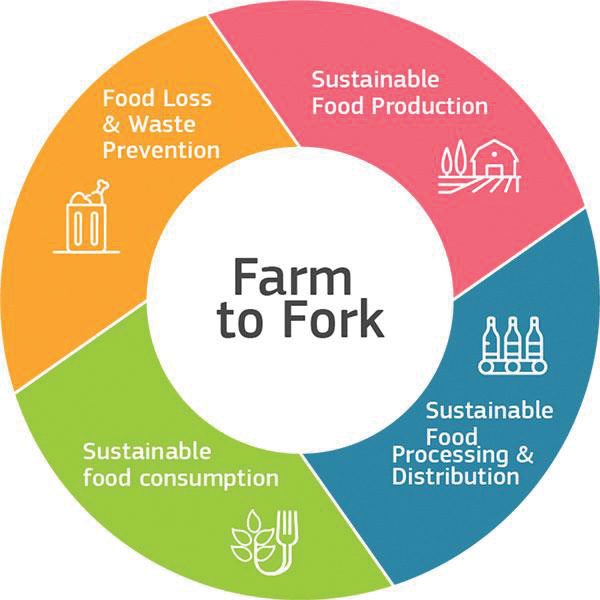

“We have got to take this seriously as time is running out for the tools we use to deal with pests and diseases. Under the European Union’s Green Deal ‘Farm to fork’ strategy, by 2030 many of the products currently used in New Zealand will no longer be accepted. This will affect exports and we are an exporting nation.

“We can make the changes to newer chemistry and biologicals; we just need our regulators to take urgency much as they did during Covid when government departments worked together to register new vaccines.”

In 2020 the European Commission launched the EU Farm to Fork Strategy which aims to ensure a sustainable food value chain. Part of that strategy includes phasing out many existing agri-chemicals.

However, Mark says greener, more targeted and safer products are bypassing the NZ market, because of this country’s regulatory systems.

“Global companies are considering focusing on countries with a more supportive regulatory regime, like Australia. Without pest control products, New Zealand would lose up to $24 billion in export earnings.

“On the heels of a recession, farming supports our economy and gives us healthy food, but government support to keep the industry thriving is long overdue. The farming sector has been hit by natural disasters, over-regulation, and pests that can wipe out harvests in one hit, yet it provides us with most of the food on our plates. In return, farmers suffer arduous regulations, delays in accessing technology and biosecurity incursions.”

Formerly known as Agcarm (Agricultural Chemical and Animal Remedy Manufacturers Association), Animal and Plant Health Association of NZ (Animal and Plant Health) is the industry association of companies which manufacture, distribute and sell animal health and crop protection products.

“We work with governments and stakeholders from around the globe to shape policy and meet the shared goals of health and safety for people, the environment and the food chain,” Mark says.

The association is so concerned about the lack of access to urgently needed products that it has released a manifesto setting out actions the Government can take.

“We want to see an increase in research and development for food production, the adoption of genetic technology, and the implementation of a faster system for registering products against biosecurity threats.

“This will protect our $7b horticultural industry and $39b animal protein market from devastating losses,” he says.

“We must support our farmers and growers to help boost our economy, maintain our exports, and ensure the health of our crops, animals, and people.”

Mark says Animal and Plant Health has a good relationship with government and the Ministry for Primary Industries and the Environmental Protection Authority, the two departments primarily involved in product regulations.

“There is recognition from many government officials that delays are a factor in discouraging offshore companies from seeking to register new products here. There is no disagreement that New Zealand needs innovation but often bureaucracy gets in the way. Good things are happening but there is still frustration about getting products to market.

“Government departments need to work with industry, listen to us and take a wider view. Let’s work together to find solutions and look outside New Zealand for what is happening elsewhere.”

Mark doesn’t want NZ to take any shortcuts in approving new products and supports the country’s stringent measures to ensure product safety. However, he does believe there are ways to speed up the process, including dedicating more staff to the work. Manufacturers are producing softer chemicals and biologicals which NZ farmers and growers want to embrace but they have to go through a lengthy and expensive process to gain registration here. “Often these companies decide it’s just too hard and New Zealand is not a big enough market to make registration economic.”

An example is a soft insecticide made from a fungus, which would replace synthetic insecticides. It is expected to take two years to gain registration in Australia but could face a three-to-four-year process in NZ, he says.

“The wine industry needs biologicals to replace synthetic pyrethrums, and these are available, but not registered here. Our industries are relying on the re-working of old chemistry and products which will soon no longer be acceptable to overseas markets.”

The arrival in NZ in February last year of the Fall armyworm (FAW) is an example of how unprepared the country is for such incursions, Mark says.

“Farmers overseas have been fighting this pest for several years. We must act faster and smarter. If our neighbours are at war with a pest incursion, we should be ready to tackle it and offer a leg up to farmers. It’s pointless joining the battleground without a weapon.

“We have one of the best biosecurity systems in the world, but we knew it would get here from Australia as moths can fly up to 100km a day when pushed by wind. There are products to control it but they are not registered here. We should have had the tools in our toolbox to deal with it before it arrived.”

The FAW mainly feeds on sweetcorn and maize, but it can survive on a range of species across 76 plant families including, potatoes, capsicums, aubergines, and some brassicas. Climate change is adding to the urgent need for new products as pests which previously could not establish here because of cooler temperatures may do so in future.

Mark says registration is generally quicker in Australia because its regulatory authorities have more staff committed to registration and also employs contractors who understand the industries’ needs and environmental issues.

“It would be ideal if products registered in Australia could also be registered here through an agreement similar to the Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) which develops food standards for Australia and New Zealand.

“That would be a long-term goal and would need to take into account that New Zealand does have different requirements including an iwi perspective.

“In the short term, our registration process needs speeding up so it takes months not years.”

Need for speed at the EPA

Staffing and resource limitations and the impacts of Covid-19 have contributed to a backlog in the registrations processed by the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) under the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act (HSNO Act) says an EPA spokesperson.

“In addition, we are receiving more applications than in previous years. We are exploring a number of approaches to address the resourcing issues and minimise potential impacts on timeframes, including streamlining our process for research and development containment applications for agrichemicals. The aim is to reduce assessment times and give applicants more transparency and clarity over processing.”

Vincent Arbuckle, New Zealand Food Safety deputy director-general says New Zealand Food Safety’s (NZFS) process to register new agricultural chemicals and related products is equivalent to comparable overseas regulators, such as those in Australia and North America.

“The timeframe for registration of new products in New Zealand is generally better than overseas.”

The EPA has received an additional $31.5 million in funding for the next four years from Budget 2023. Just over $6m is specifically for hazardous substances work and will be used to increase capacity to process the current backlog of hazardous substances applications.

The spokesperson says the EPA is not aware of any international companies bypassing Aotearoa New Zealand because of the fees involved in the application process for new hazardous substances.

“These fees are significantly lower in New Zealand than in many other comparable countries and regions, including Australia and the European Union.”

While there are similarities with Australia’s regulatory system, NZ has a unique environmental and cultural context within which applications for new hazardous substances are assessed. Those considerations are written into the HSNO Act that governs the EPA’s work.

Recent amendments to the Act, mean EPA can make better use of information from international regulators for some hazardous substance applications.

“Earlier this year, we publicly consulted on the list of international regulators we propose to draw information from. We are currently reviewing the submissions received, and the proposal will be presented to the EPA board for consideration later this year. Some substances that have been approved overseas may have an easier pathway should they meet the international regulator criteria.”

The EPA undertakes a rigorous assessment for every hazardous substance application, including agrichemicals. “We rely on scientific data and evidence, economic information, and local information, as well as Aotearoa New Zealand’s unique cultural perspectives to ensure we continue to protect people and our environment.”

Vincent says the small size of the NZ market means it is often not a priority for manufacturers of new chemistry.

“Manufacturers tend to focus on crops such as soya, corn, rice, and wheat. These are produced at a large scale in certain countries and are either not grown here in New Zealand, or the size of the crop here is insignificant compared to these other countries. Generally, manufacturers will enter markets where they can get a quicker return on their research and development investment.

“NZFS recognises the small size of the New Zealand market by ensuring regulatory requirements and processes are fit for purpose for the New Zealand situation while remaining robust. This means the regulatory approval requirement for manufacturers is not a significant component (eg cost) in their decision on whether to market or not a new compound in New Zealand.

“NZFS continues to review and refine its regulatory requirements and processes which includes seeking the views of manufacturers and industry bodies, including Animal and Plant Health NZ.

“NZFS has been working with regulators of agricultural chemicals and veterinary medicines globally for several years to make regulatory processes more efficient. The final decision on the application remains with each regulator, as farming and growing practices differ between countries and regulators do not consider abdicating their sovereignty on decision making,” he says.

Farm to fork – EU

Farm to fork – EU

The Farm to Fork Strategy is at the heart of the European Union’s European Green Deal which has the aim to “make food systems fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly”.

The EU website states: “Food systems cannot be resilient to crises such as the Covid-19 pandemic if they are not sustainable. We need to redesign our food systems which today account for nearly one-third of global GHG emissions, consume large amounts of natural resources, result in biodiversity loss and negative health impacts (due to both under- and over-nutrition) and do not allow fair economic returns and livelihoods for all actors, in particular for primary producers.

“Putting our food systems on a sustainable path also brings new opportunities for operators in the food value chain. New technologies and scientific discoveries, combined with increasing public awareness and demand for sustainable food, will benefit all stakeholders.

“The Farm to Fork Strategy aims to accelerate our transition to a sustainable food system that should:

- have a neutral or positive environmental impact

- help to mitigate climate change and adapt to its impacts

- reverse the loss of biodiversity

- ensure food security, nutrition and public health, making sure that everyone has access to sufficient, safe, nutritious, sustainable food

- preserve affordability of food while generating fairer economic returns, fostering competitiveness of the EU supply sector and promoting fair trade

The strategy sets out both regulatory and non-regulatory initiatives, with the common agricultural and fisheries policies as key tools to support a just transition.