Phil Edmonds

Little can be said about banks at the moment that doesn’t raise heartless sighs. The credit squeeze (call it what you will) is no longer a ‘what if’, but real in the agri sector, with much anecdotal experience pointing to very tough conversations being had between rural bankers and both indebted and debt-seeking clients.

The fallout is likely to be significant and felt widely among farmers. But perhaps the lasting impact of banks stemming the flow of agri lending will be felt more widely still, by all New Zealanders, as an inevitable slowdown in environmental ‘catch up’ investment will weaken our long-term competitiveness in premium-paying markets.

Realignment of the rural banking landscape is now well rehearsed. Banks are focused on repairing their balance sheets to address what the Reserve Bank has for some time referred to as an overly indebted and therefore vulnerable dairy sector. That means calling in principal repayments, and any prospect of new lending being firmly tied to profitability.

The RBNZ has proposed new capital requirements on banks to deal with the ongoing debt risk, and in turn banks have said the cost of new restrictive practices would be passed on to farmers.

Massey University banking expert David Tripe says lending is going to get more expensive because if banks are going to have to hold more capital with the same levels of return they themselves will have to earn a bit more.

In a submission to the Reserve Bank’s capital framework review, accounting firm KPMG estimates the five banks that hold 98% of all agri lending will reduce their lending by between 15% and 25% – mainly in dairy, if the new rules are adopted.

In response, ANZ has signalled its intention to reduce its dominant market share of rural banking and others are restricting their lending to the dairy sector. Rabobank though has stood apart and assessed the landscape as an opportunity to increase its presence. It recently started a television advertising campaign highlighting how online deposits with the bank are exclusively used to fund New Zealand’s food and agricultural producers.

“In some respects we are just doing more of the same and being consistent in the marketplace,” Rabobank NZ chief executive Todd Charteris says. “But if we look at the outlook from a commodity return point of view, the markets look strong and there is an opportunity in the marketplace right now.

“From a cash flow point of view, all farmers have a really good opportunity to create more stability in their balance sheet through investment or debt reduction. And that is a positive. As well as supporting our existing customers, our priority will be to look for opportunities to grow within our risk profile.”

Rabobank’s outward enthusiasm for the sector is encouraging, but comes with a noteworthy caveat – it is only interested in low hanging fruit. “We will absolutely explore growth opportunities, but we have no intention to operate outside our own risk appetite,” Charteris says.

In line with the value not volume mantra, Rabobank’s enthusiasm for the sector’s growth potential is more sophisticated and nuanced than rural lending strategies of the past. Rather than limit its focus on the impact its lending will have on increases in economic production, Rabobank says its lending support needs to help create sustainable businesses and recognises some of those sustainable indicators are non-financial, including higher animal welfare standards and sustainable freshwater resources.

“The word sustainable is overplayed at times, but what we want to do is help create sustainable business models that can endure. And if farms are wanting to invest in measures that will make their long-term sustainability sound, we would look favourably on that,” Charteris says.

It’s not only Rabobank talking about the sector facing a transition period, and the need to finance it. ANZ agricultural economist Susan Kilsby notes the industry, including Government and lenders are working with producers on how to best help farms transition to economically sustainable and resilient businesses by minimising environmental impacts.

Great – the banks say they are keen to play their part. But all said and done, the onus remains on farmers to show banks they are able and committed to play theirs.

ANZ’s Kilsby says that while New Zealand producers are working hard on this, stronger commitment to compliance is needed to drive higher prices. For Rabobank, any discussion of further lending starts with a compliance check. Charteris said the bank will ask questions like do you have a farm plan, what proportion of your waterways are fenced off or planted as a means to really get an understanding of the business readiness for potential changes.

So how well placed are farmers to prove their existing economic and environmental resilience to justify new lending for further sustainability enhancements?

Massey University management lecturer James Lockhart suggests many farmers are not well positioned for this transition.

“Historically as a sector we have ignored the cost of environmental expenditure. Now we are in catch up mode. If you take it back to decision making and farmer owners attitude to risk, typically what they have done is discounted the cost of environmental compliance or enhancement and haven’t seen it as a capital expense that sits in the short-medium term.

“You have farmers who have discounted their equity structure and as the compliance regime has gained traction they are going to struggle to meet the associated costs.”

While the banks are outwardly positive about their willingness to assist farmers in this period of transition, Lockhart doubts the extent to which banks will be able to help, given their determination to see farmers focus on debt repayment.

“I suspect there will be reluctance among lenders to finance environmental enhancement as it asks the question of where the security of that additional lending comes from. Heavily indebted, heavily geared dairy farms in particular will have lenders increasingly reluctant to put more debt on those properties to meet environmental compliance,” Lockhart says.

This sense is certainly backed up by individual farmers’ experiences.

One farmer spoken to by Dairy Exporter said no one facing imminent investment on compliance will be confident going to their bank.

For those who don’t have effluent storage or have unlined ponds that might be susceptible to leaking, the need for significant investment is coming in the short-term. Looking further out, perhaps 10 years, it is conceivable that all dairy farms will need a herd home to effectively capture urine between March and August.

None of this is a recipe to pay back more principal.

This represents the kind of ‘compliance creepage’ that has become a real issue and some farms are going to be vulnerable – particularly those that have been lax to date.

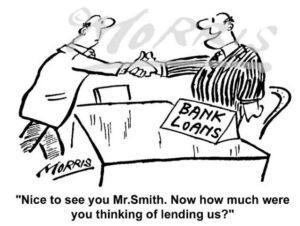

It is exactly these potential situations that are driving the shape of bank conversations with farmers in a direction of ‘show us your compliance first, then we’ll talk lending’. After all, the last thing a bank wants to hear is a client telling them Fonterra is no longer going to pick up their milk because they’ve got too much non-compliance.

It might not be expressed as sympathy, but there is an acceptance that banks are right to take this approach.

“If we are heavily geared, and we don’t have free cash flows and have to borrow and lenders are wanting principal to be paid down, does that pose a constraint in terms of the rate of environmental improvement? The short answer is of course it will. This will be through no fault of the lender, but of farmers having discounted the cost of environmental improvement,” Lockhart says.

And despite rural confidence surveys showing farmers are feeling more and more pressure from banks, there is an understanding that whatever happens, banks will always want to maintain their profit. Farm business consultant Don Fraser says “you need to acknowledge banks are lending the money with an understanding the farmer can service the debt and look after their money for them. People need to remember that the bank has ‘first’ on everything.”

This takes us back to the measures that will allegedly rein in rural banking profits – the RBNZ’s proposed change to regulatory capital requirements, the costs of which many say will be paid for by farmers, not the banks.

KPMG is in no doubt about the negative impacts of these changes. In its submission to the RBNZ, it said they will “prevent or seriously delay capital spend needed by good dairy and other farmers to lift farm economic, environmental and animal welfare performance at a time where investment in these areas is critical to the future prosperity of the sector… There will be an incentive to persevere with lower cost, lower tech, higher environmental and reputational risk, farming practices.”

So what’s the end game? It probably depends on farmers’ appetite to battle on for diminishing reward.

KPMG is fearful of a worst-case scenario – a sector crash. The accounting firm says farmers and bankers understand the current situation is unsustainable for some farmers and “the consensus view is that of a crash in the price of rural land, particularly dairy, or regions where dairy prices have underwritten local land values.”

It notes that this would occur at a particularly badly timed juncture where the “threats of the accumulated negative impact on farm values coincide with capital-hungry demands to transform farming practices.”

A crash in farmland prices would encourage older farmers to hold on to their farms with minimal future investment, preventing younger farmers entering the market with the skills and attitude more able to deal with the contemporary environmental issues.

Lockhart says a fall in farm values is inevitable, but there is likely to become a clearer demarcation between those farms that are environmentally sustainable, and those that will require major investment to become so.

“When it comes to farm sales, there is no question that the level of environmental compliance and sustainability will be embedded in the value of a particular property. Over the past 10 or 15 years, that cost of compliance hasn’t been reflected in the price paid for conversions for example, and we’re in catch up mode.”

Meanwhile, the distribution of problematic debt might also skew the general softening of land prices towards larger farms.

A common perception that most of the younger farmers who are in the industry and want to buy farms are already indebted. That only leaves sharemilkers but at current prices and lending criteria, they’re likely to be limited to about 60ha.

With banks signalling an unwillingness to lend more to dairy and overseas investment off-limits, there could be indebted farms with 100 hectares-plus, needing to be sold under pressure with no one to buy them. This suggests any farm of above average size could potentially face a real fall.

Whatever way you look at it, the outlook for all industry participants is gloomy.

On the value of committing to gold-plated, onfarm environmental standards though, there are still some splits in opinion on the extent to which that is appreciated in the marketplace, and ultimately its bearing on farmland prices.

On one side KPMG remains in no doubt of the critical importance in addressing environmental shortcomings.

“A retrenchment from aggressive capital investment in shoring up our on-farm practices will be a fall from grace for our premium-priced agricultural outputs… This would have a significant impact on the overall economic performance of our country, and the wellbeing of New Zealanders.”

Minister for Agriculture Damien O’Connor also falls into this camp; his stock answer to those questioning the Government insistence that agriculture makes a meaningful contribution to a zero carbon future is to cite conversations with trade officials, who have made it clear the likes of the European Union will do anything they can to stymie improved access for NZ products – including demanding the most stringent rules around environmental practices.

But Lockhart warns we need to be careful about assuming market hysteria over alleged animal welfare and environmental mismanagement.

“In the case of dairy, we are not necessarily seeing market signals.” To rectify this, he says the likes of DairyNZ could be doing more to provide transparent information to farmers about the marketplace and the level of price premium obtained for products with environmental credentials.

If this was made clearer, it might remove those doubts, and possibly have an influence on farm prices.

Banking: A new norm

Before 1984, banking in New Zealand was heavily regulated. There was no incentive for banks to compete on any level.

New Labour Finance Minister Roger Douglas opened up the banking industry to free market forces, but it wasn’t until 1990 that banks really started to compete in the rural market. With access to unlimited funding, banks had plenty of money to lend, and farmers were willing to borrow it, Southland based Agri Business consultant Peter Flannery writes in a special report published on NZ Dairy Exporter’s website.

From 1990 to 2019, farm debt has lifted 15-fold. Farm values lifted nearly 12-fold and are now declining, but debt is not. Since the global financial crisis banks have had to operate under increased scrutiny and regulation from the RBNZ, and this change is now impacting on banks and therefore their client. This is going to cause significant change and maybe disruption. How banks respond will set them apart from each other, and the same applies to their/our clients.

- See the full story by Peter Flannery at: https://dairyexporter.co.nz/banking-back-to-the-future-or-forward-to-the-past/