Counting their chickens

Experience with organic free-range poultry has led a former Hawke’s Bay share-milking couple to breeding pedigree Jersey cows. Words and photos Anne Hardie.

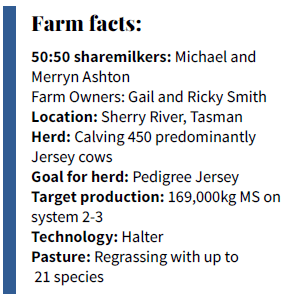

Sharemilkers Michael and Merryn Ashton are aiming at a pedigree Jersey herd and it is all because of chickens. Not just any chickens, but quality poultry that wins a national title because of the selective breeding behind it.

It was Michael’s passion as a kid on his parents’ dairy farm in Hawke’s Bay and he went on to become a poultry judge and won the national best in show in 2017 with his top bird, a white Wyandotte pullet.

That passion for stock and selecting the best continues into the herd they bought from the owners of the Tasman dairy farm two seasons ago.

While sharemilkers breeding a pedigree herd is a bit outside the norm, so is their leap into Halter technology in just their second year and their mixed-species pasture that includes up to 21 species which are now being planted into soil prepared by a spike rotor.

Two years ago, the couple were in Hawke’s Bay on Michael’s parents’ dairy farm near Waipukurau which he had managed for 10 years, including making the breeding decisions to produce a fully A2/A2 Jersey herd.

While he milked cows, Merryn who was a former radiation therapist ran their organic, free-range egg business.

Eight hundred laying hens were part of the dairy farm’s pasture rotation, following behind the cows. Solar panels on the hen houses enabled them to add light into the houses early in the day to encourage the chooks to get up and lay their eggs, then get outside to eat more.

Then came the move to sharemilking to be in charge of their own business and that led them to Gail and Ricky Smith’s Sherry River farm near Tapawera where the narrow valley floor is largely dairy country bordered by reasonably steep hills.

They sold the organic egg business and their house in Hawke’s Bay to buy the existing herd for a three-year 50:50 contract. They have since extended the contract for another year and with three kids, William, Lily and Charlotte aged between seven and 14, they are “settled and happy”.

About a third of the initial herd of 394 cows were Jersey, another third crossbred and the remaining third large Friesians, so they had a wee way to go to reach pedigree Jersey status.

After their first season they replaced the Friesians with Jerseys from top breeder dispersal sales, altered the rails in the 28-bail rotary to suit smaller cows and last year calved 396 cows on more land.

The extra land comes from the use of Halter technology, using the hillsides above the original 144-hectare milking platform to take the total milkable area to 215ha. It is still a work in progress as the pasture improves with better grazing, milking the two and three-year-old cows once-a-day (OAD) through the season and following with carry-over cows. But first, the genetics which has already lifted the herd’s breeding worth (BW) to within the top 5% in the country – which they say is useful but “not the be-all and end-all” of their breeding goals. It is one aspect though and the herd they bought with a BW of 144/53 is now 239/48, while production worth (PW) has gone from 175/65 to 280/63.

“Because our herd is our asset, it’s relevant. It’s a consideration but not everything,” Michael says.

Selecting Australian genetics

In their goal to achieve the type of cow that is capacious, has a good udder, low somatic cell count and generally a good type, they selected 18 bulls from five different breeding companies for this year’s calving. Tighter payout meant they chose younger bulls from Jersey Futures which are not yet proven but are genome-tested and have the traits they sought.

Among their selection are Australian genetics for a bigger animal with better type and mammary. Michael says they tend to stay away from American genetics which are tall and leggy but lack the capacity to utilise a New Zealand grass-based system. Fifty straws came from a young polled Australian bull with good figures called Goldband, while other Aussie bulls picked for the herd were Askn, Valenblast and Invincible. From NZ genetics they chose Carrick.

Three of their R1 heifers have contracts with breeding companies with the potential for a bull calf to be picked up by the company that could provide royalties if they prove their worth. If they get heifer calves, they get a good animal for their own herd.

“It tells us there is potential in our herd and more income down the track,” Merryn says. “But it also gives us enjoyment because that’s where Michael’s passion is.”

Polled genetics is an area they want to explore more in the future as the performance in those genetics improves.

This past mating they used artificial insemination (AI) over the entire herd for 12 weeks.

For the first three weeks, the top 75% of the herd received sexed or non-sexed nominated Jersey straws and the bottom 25% received Belgian Blue straws.

For the second three weeks, the top 25% of the cows received nominated Jersey straws and the bottom 75% Belgian Blue. When they got to the last six weeks of mating, short-gestation crossbred straws were used to help condense calving dates and achieve more days in milk.

Last year’s AI budget was $27,327 which they plan to reduce to $18,500 this year by eliminating sexed semen because they did not get the results to justify using it again this year. The focus will be on getting more cows in calf early and achieving more days in milk.

Next year, with more time and knowledge using Halter, they hope to gather more pre-mating heat information and condense mating to nine or 10 weeks. Meanwhile, the Belgian Blue straws are from English genetics that are bred specifically for the dairy sector and are short-gestation to reduce calving by eight to 12 days, as well as easy calving.

The result of the Belgian Blue genetics has been easy calving from the 90 Jersey and crossbred cows and good-sized calves that “hit the ground running”.

The calves arrive between early August and mid-September, are easily identifiable and are pre-sold to a local calf rearer at a “fair price” so that the buyer takes the lot, while providing a good margin for Michael and Merryn.

She says getting the calves pre-sold, collected two to three times a week and no rejections is more important than achieving a premium price. The cows are in milk earlier by using the shorter-gestation straws and they calve easily so recover faster.

“They grow so well that the rearer gets them weaned and big enough before summer and they can be finished before their second winter.”

In the future they may synchronise the 30 top heifers so they can AI them all on one day, two days before the official start of mating with slightly longer-gestation Jersey straws and then put their best home-bred registered bulls out on the first day of mating. That way they overcome the challenge of inseminating the heifers as they cycle on a distant block.

This past mating, Michael and Merryn had newly installed Halter technology available which worked well for heat detection in the milking herd.

“Halter will give us a list of cows on heat and a LED light on the collars lights up so we can draft them off during morning milking, ready for the AI technician.”

Empty rates still have room for improvement following 15% in their first season and 13% this past season. The two and three-year-old cows that are milked once-a-day (OAD) on the hills fared considerably better with 7% empty.

Using the sidlings

The reason for sending young stock off the farm to graze is because of those hills. Michael and Merryn want to utilise all the sidlings as part of the milking platform and now use 40 carry-over cows to work behind the herd to improve the pasture.

“We’re looking at reducing replacements and buying in more high-quality empties,” Michael says. “We can use them as a tool but also improve the herd by getting other people’s top animals. Two of the empties we bought have contracts on them so they’re really good animals.”

Grazing the hills has enabled them to bring more cows into production. In the past two seasons without the hills in the milking platform, they have produced 130,000kg milksolids (MS). This year, with more room and calving a larger herd of 450 cows, they expect to achieve about 169,000kg MS operating a system 2-3. To achieve that target and operating a system 2-3, the twice-a-day herd on the flats will need to be producing 420kg MS/cow and the OAD herd on the hills 300kg MS/cow.

Last year, they bought 120 tonnes of meal for in-shed feeding and Michael says they needed more in spring, so were “chasing our tails” until they implemented Halter and closed the gap with improved pasture quality and utilisation. This year they have a larger herd and are considering buying in up to 200t of meal and 50t of molasses to feed in-shed, weighted heavily to spring to maximise peak milk.

“If we can set them up well with the supplement they need during the crucial time, then we can complete the season heavily pasture-based with the help of Halter.”

They’re hoping for a calmer spring because last season they were caught without staff and 100 heifers had to come home from their grazing in the Rai Valley because of the August floods which wreaked havoc on the grazing block.

When they introduced Halter technology in October, everything changed for the better, including a 10% increase in production because they could manage the pasture more for better performance.

Suddenly, they had more time for other things and threw themselves into the Dairy Industry Awards where they were finalists and won the dairy hygiene award.

Hygiene in the dairy is pretty straightforward for Michael who worked on a raw-milk dairy farm and hence at the Sherry River farm they achieved 94% of days of excellence where the somatic cell count is less than 150,000. Their average was 106,000 and consequently both seasons so far have been grade-free through the dairy which is set up with automatic cup removers and teat spray, in-shed feed, Milk Hub and automatic drafting.

Merryn says good milk quality is attributed to keeping the dairy meticulously clean and having robust protocols in place. This season they want to do even better.

Introducing Halter

When they moved to the Sherry River farm two seasons ago, the milking platform spread over 144ha of the valley floor. Halter’s technology using smart collars and a simple app has enabled them to increase that to 216ha using its virtual fencing to better graze the moderately-steep hills that rise above the flats.

The two and three-year-old cows are milked once-a-day (OAD) on the hills throughout the season, while the older, higher-producing cows are milked twice-a-day (TAD) on the higher-quality land.

“We couldn’t have milked on the hills before,” Michael says. “We can use Halter to put breaks on the hills and that makes them eat the grass better and improve the pasture.”

Initially they kept young stock on the farm, but they could not push them behind the cows on the hills and now graze them off the farm in preference for 40 carry-over cows.

The carry-overs include their top empty cows as well as good-quality empties from three other farms and they work on the rougher pasture left behind by the milking herd.

“It gives us more usable land and the quality keeps improving,” Merryn says.

It is just one of the reasons they decided to spend the money and introduce Halter into their system. Since implementing the system, they have paid $16 per cow per month throughout the year, but say they are looking forward to the new, more-affordable pricing structure that will be introduced by Halter in the coming months.

The Ashtons winter 150 cows off the platform, so those cows have their collars removed for that period and there is no charge.

The Halter collars went on the cows in mid-October last year, so it is still early days. But Michael and Merryn are already sold on the technology.

“In my opinion it will become mainstream,” Michael says. “We wouldn’t go back and we take it for granted now.

“On our steep paddocks, we can schedule the cows to shift in the app and they come in calmly by themselves.”

Through audio cues, cows learn when the virtual break has been moved so they can go forward and graze or get directed toward the dairy for milking.

Vibrations indicate to the cow that she is on the right path. Merryn says the audio cues prompt the cow to turn left or right and vibrations are a positive reinforcement to move forwards.

Stronger cues follow if needed and if the cow ignores those cues, the collar eventually delivers a low-energy pulse. She says the cows quickly learnt to predict the cues which means they can avoid them and cows seldom get to the pulse stage now.

When it comes to animal welfare issues, she says they are satisfied the technology protects the cows, with multiple safeguards in place that make it impossible for a farmer to manually issue a pulse.

As farmers, she says every feed break and movement is carefully considered and supported by the capabilities or limitations of Halter.

Changed herd dynamics

“Within three days we stopped using reels and standards,” she says. “It’s designed around their natural instincts, so it works with them.

“It’s changed the dynamics of the herd too. We can go into the paddock and the cows don’t rush to the gate or the break to be fed and that protects the pasture. They don’t associate the farmer or the vehicles with being fed, so are relaxed and content when we walk through the herd.”

Whoever is rostered for morning milking no longer has to head out in the dark in all weathers to bring the cows in and simply turns up at the dairy to find the cows waiting to go in.

The farm has been drone-mapped and the Halter technology uses that to work out how long it will take the cows to get to the dairy from each paddock and they are prompted accordingly.

A quick check on the phone shows the location of every cow, so it is easy to see if any are left in the paddock.

If a cow is sick or has a problem, multiple safeguards kick in that cause the collars to stop sending cues after a period of non-response. Merryn says they can also manually pause collars of individual cows that have shown a health alert or if there are other concerns. Pre-Halter, it took the cows more than an hour to head to the dairy from the furthest paddock, but now it is about 45 minutes because they keep walking forward.

“You still have those lead cows, even going to the cow shed,” Michael says. “They have to keep that forward angle, so it stops those lead cows trying to turn around and bully other cows. Which means it’s nice and calm without anyone getting bullied or picked on. We’ve had a significant reduction in lame feet because of that.”

Any sick cows show up as an alert with the technology and are pulled from the main herd. Because they no longer need reels and standards, Michael says it is easier to manage smaller herds such as a few “special needs” cows.

The technology has changed the choice of paddocks and distance for milkings as well.

As they only need one person for each milking now that the cows head to the dairy by themselves, the cows can do the longer walk in the morning when it is cooler. In the past, the herd would graze paddocks closer to the dairy at night to make it easier to bring them in the next morning.

“We can make them do the big walks in the morning when it is cool and the shorter walks in the afternoon when it is hotter,” Michael says.

Now the cows walk themselves to the dairy, the quad bike is used less, which means less petrol and they expect it will need less servicing, which reduces those expenses.

Taking a holiday break

Going on holiday has got a lot easier. After the cows were dried off, Michael and Merryn headed off to Waikato for a few days and left their sole employee, Talia Manson, in charge, while moving the feed breaks themselves by using the Halter technology on their phones.

“Michael did all the breaks from Waikato and Talia just had to make sure the right gates were open at the right time and check water. It means she can manage the farm on her own.”

Merryn reckons the technology saves them four to five hours of work a day between moving reels and standards and rounding the cows up for milking. In effect, that has eliminated the need for a second employee on the farm during the busiest periods.

“The staff shortages in the dairy industry means farmers will be using more technology. Last season we had February and March by ourselves without staff and we have three kids, yet we managed because of Halter.

“We can justify the expense of Halter because we don’t have that extra staff member through calving and finding staff in this area is really challenging, especially when we don’t have an additional house. Halter doesn’t have days off or sleep-ins either.”

Halter not only eliminates the need to physically move pasture breaks but does it more accurately, Michael says.

They use a platemeter over the paddocks and add that information into the technology so it can allocate feed for each cow.

It calculates the average cover on the farm and the rotation length to use it to work out the appropriate breaks for the cows.

Michael says they are now utilising the grass better because they can more accurately feed each cow its requirements rather than trampling surplus grass. Simply put, the cows are fed better on the same grass, he says.

“There’s still so much more potential in the app; we’re just scratching the surface of utilising the information,” Michael says. “Our initial focus was fencing, health and and mating.”

Diversity in pasture

Nature does not do monoculture which is why Michael and Merryn are developing such a diverse pasture mix on their milking platform.

They are sowing up to 21 different species into paddocks each year that is their own mixed bag, using chicory as a base and adding the rest to cover cow nutrition, support the soil and cater for climate challenges.

It is a summer dry climate in the Sherry River area and the farm has no irrigation apart from 30ha of effluent on paddocks close to the above-ground tank. Their mix is designed with the summer dry in mind and a cold winter.

Into the mix goes prairie grass, cocksfoot, perennial ryegrass, timothy, red clover, white clover, crimson clover, Persian clover, arrowleaf clover, balansa clover, lucerne, yarrow, phacelia, linseed, plantain, vetch, sunflower, chicory, daikon radish, rape and lotus.

The mix has been developed by talking to people using diverse mixes and continuing to tweak the species and ratios. Some species are annuals, but the majority are perennials that will also self-seed, with different species catering for different times through the season.

“Everything has different growth cycles and growth patterns and by putting it together, it fills the gaps,” Michael says.

The Daikon radish is in the mix for its large tap root to puncture the soil and pull up moisture from further down in the soil and the cows love it. Phacelia is also planted for the soil, though they will reduce it from 200g/ha last year to about 100g as it was a “touch too-dominant” in the pasture.

“We’ve included sunflowers which the cows don’t eat, but they have a big root structure that opens the soil and they create shade and shelter for other plants,” Michael says. “They added a little bit of joy too. There were so many guys coming and getting flowers for their wives or partners.” The taller plants provide feed through summer and shade the next level of plants which come through in autumn.

Last year they sprayed and sowed 15ha of the farm in October and began grazing it from the beginning of January. This year they will sow another 20ha and rather than spray they will use a second-hand spike rotor they have purchased for $9,300 which shred the turf and just the surface of the soil enough to sow seed.

Michael says he used one on the certified organic family farm in Hawke’s Bay where it gave seed an opportunity to establish without spraying and destroying the soil biology. The shredded turf leaves a clumpy surface that “doesn’t look pretty” but works well, especially if the wind picks up as the soil is not blowing away. Some of the previous grass will grow again and he says that is not a problem.

Using so many species in the mix means they do not need to plant thickly and the drilling rate is quite low per hectare which keeps costs down. The seed price works out at $273/ha, whereas a turnip crop for summer feed would be $78/ha plus regrassing at $335/ha. Less is spent on nitrogen as well, with just 60kg/ha used across the farm.

Michael says the pasture mix is a good way of moving feed because it is removing paddocks in spring when there is surplus to control and adding more into the system in summer when they need it. They still make about 400 bales of balage to feed to the herd through winter, summer or whenever there is a gap in feed.

So far, their seed mix has performed well for the herd and after paddocks were sown in October, they managed three grazings through summer and autumn on a 40-day rotation. Those paddocks have been shut up through winter and will re-enter the rotation during spring.