Anne Lee

Having a good understanding of marginal costs, in particular the marginal cost of the extra milk produced by adding in supplement, will go a long way to focusing the mind on what actually creates a profitable farming system, former DairyNZ scientist John Roche says.

Having a good understanding of marginal costs, in particular the marginal cost of the extra milk produced by adding in supplement, will go a long way to focusing the mind on what actually creates a profitable farming system, former DairyNZ scientist John Roche says.

Roche told about 900 people who attended the Pasture Summit in November that while it’s not a new concept it’s worth repeating for as long as it takes.

“One of the reasons we keep having the discussion is that for the 10 years we’ve talked about profitable and unprofitable systems.

“People who had profitable systems knew they were profitable, their accountant told them so; they were able to pay down debt.

“But, some of the milk they were producing wasn’t profitable. Their base milk production was profitable but some of their marginal milk production wasn’t.”

Marginal milk is the extra milk made by changing the system.

Well-managed grazing has been the forgotten hero of conservation with research showing moderate intensity farm systems give optimum carbon sequestration and return of carbon to the soil when compared with low or high-intensity systems.

The laws of economics show that profit is maximised when marginal revenue – the extra income gained from added production – equals the marginal cost.

Initially when we make changes to our systems, add in supplements or intensify the system you get some economies of scale. The farm dairy is big enough, labour can cope and electricity doesn’t go up very much.

But as the change becomes greater the cost for every extra kg milksolids (MS) produced goes up too.

“That’s not a problem until the marginal cost exceeds the price you’re getting for the additional production – in our case that’s milk price.”

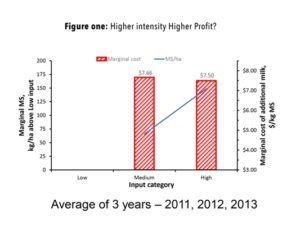

A study at Lincoln University by Wanglin Ma, Alan Renwick and Kathryn Bicknell and published in the Journal of Agricultural Economics 2018 looked at the marginal cost of additional milk production using New Zealand farm data averaged over three years 2011, 2012 and 2013.

They found the marginal costs of milksolids produced using supplementary feed was between $7.50 and $7.66/kg MS. (figure one)

They found the marginal costs of milksolids produced using supplementary feed was between $7.50 and $7.66/kg MS. (figure one)

That meant the milk price would have needed to be more than $7.70/kg MS for the additional milk to have been of value – to have been profitable.

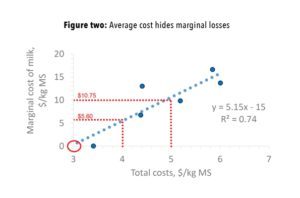

An analysis done with one farmer shows how the average cost of milk can hide marginal losses.

In that case – figure two – it’s apparent that the base system can produce milk for a little more than $3/kg MS, Roche said.

As supplement lifted, the cost of production rose on the subject’s farm and at $4/kg MS average cost the cost of marginal milk was $5.60/kg MS. At $5/kg MS cost the marginal cost jumped to $10.75/kg MS.

As supplement lifted, the cost of production rose on the subject’s farm and at $4/kg MS average cost the cost of marginal milk was $5.60/kg MS. At $5/kg MS cost the marginal cost jumped to $10.75/kg MS.

“In New Zealand there’s a lot farms with a total cost of production at $4.85/kg MS which suggests there’s a huge chunk of marginal milk being produced at the $8-$9/kg MS price tag.”

Recent marginal analysis of a farm systems experiment led by former senior DairyNZ scientist Kevin Macdonald close to 20 years ago, that had originally looked at the productive and economic responses to supplement, showed the differences in marginal cost between filling a genuine feed deficit and using it to push production. (table one)

In the study cows were at a 3.35 cows/ha stocking rate or 4.41cows/ha.

In the study cows were at a 3.35 cows/ha stocking rate or 4.41cows/ha.

At 3.35 the comparative stocking rate (kg liveweight/t drymatter) was 86.

At 4.41cows/ha they were either fed no supplement or 1.3 tonnes SM/cow as maize grain or 1.1t DM/cow as maize silage.

The marginal analysis on the various systems showed that when supplement was used to fill genuine feed deficits the marginal milk cost $6.33/kg MS in the grain fed scenario or $5.54/kg MS in the maize silage scenario.

“You could just about live with that depending on milk price but if you look at the idea of using supplement to lift stocking rate the marginal cost of that milk was between $7.80 and $8.”

When supplements are being used to fill feed deficits they should be bought on a cents per megajoules of metabolisable energy basis and not how much MS/kg supplement drymatter (DM) will be produced.

“Strategic use of feed to fill genuine feed deficits depending on milk price can work but if you’re doing that every year that’s not strategic use it means you’ve pushed your stocking rate up and you need that feed all the time.

“In that situation the feed is very expensive.”

Data from New Zealand and Ireland tells a similar story when it comes to the hidden extra costs that go with increasing supplement.

For every extra dollar spent on imported feed, operating expenses go up by $1.53/kg MS in Canterbury and $1.68/kg MS in Waikato.

In Ireland it’s €1.53/kg MS and in the United Kingdom £1.62.

Roche said when farmers in New Zealand and Ireland were asked why they fed supplements the answers could be grouped into four reasons:

- To prevent body condition score (BCS) loss in early lactation – with the aim of improving BCS faster for reproduction.

- Ease of management – cow flow.

- Cow-centric judgements – wanting to have full cows.

- To increase milksolids production to increase profit.

Generally feeding supplements does not increase profits – it does the opposite by increasing costs with the expensive marginal cost of additional milk production eroding the bottom line.

The other major myth Roche aimed to debunk was that supplements fed shortly after calving will prevent BCS loss and improve reproductive performance.

Again the opposite could be true with several studies showing that feeding high starch or sugar diets leading up to and during mating may reduce the time for cows to cycle but will increase early embryonic loss and reduce pregnancy rates to artificial insemination.

BCS at mating is important but is influenced by BCS at dryoff in the previous season and through the winter period so that cows are at target BCS at calving not by feeding post calving.

BCS at mating is important but is influenced by BCS at dryoff in the previous season and through the winter period so that cows are at target BCS at calving not by feeding post calving.

For the first 30 days cows after calving cows are genetically programmed to lose BCS and put energy into milk production.

Even cows fed a total mixed ration lose BCS post calving at a similar rate to those on a pasture only diet.

Teagasc Moorepark scientist Brendan Horan says the Irish dairy industry is recognising that from a global markets perspective it’s a great time to be a grass-based sector.

Consumers are engaged and care about how their food is produced and grazing-based, grass-fed systems offer a positive provenance story – but we have to tell it, he warned.

Research must respond and help farmers create resilient systems that:

- Improve the livelihood of farmers through consistent profits insulated from price and climate shocks.

- Provide simple and labour efficient systems with minimal interventions.

- Improve products and reduce environmental and animal welfare pressures.

Well-managed grazing has been the forgotten hero of conservation with research showing moderate intensity farm systems give optimum carbon sequestration and return of carbon to the soil when compared with low or high-intensity systems.

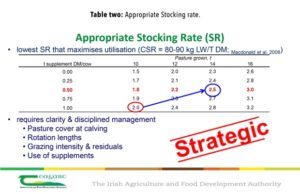

Getting stocking rate right is imperative and, based on research carried out by Macdonald the most appropriate level will be a comparative stocking rate of 80-90kg liveweight/t drymatter grown.

In Ireland stocking rates are low at an average two cows/ha with about 1t DM/cow of supplement fed and 10t DM/ha of pasture grown.

The aim is to lift stocking rate to 2.5 cows/ha, reduce supplement to 500kg DM/cow and grow 14t DM/ha of pasture.

A grazing system that maximises pasture eaten and balances stocking rate and animal demand with home grown pasture supply can reduce environmental impacts such as nitrate leaching.

Horan cited Roche’s study that showed increasing stocking rates to match cow demand to seasonal peak pasture supply coupled with strategies such as early culling and dryoff to achieve BCS targets at the end of the season while matching the diminishing feed supply through autumn, actually reduced nitrate leaching as cow numbers reduced over the high-risk autumn period.

When the carbon footprint was analysed for the systems change experiment Roche had discussed – going from 3.5 to 4.1 cows/ha with varying amounts of additional supplement – the 3.5cows/ha system produced a total of 87.5t CO2 equivalent compared with 95, 128 and 113 for the more intensive systems.

But Horan said the overall positive story of grass-fed, pasture-based dairying had been lost.

“We’ve confused the story with something else entirely – importing feeds in the system and the impacts that has.

“Whether we’re talking about nitrogen fertiliser or imported feeds – that’s adding nutrients in the system and that changes this basic story and associates it with negative effects.

“We need to disentangle these two things and think about them separately,” Horan said.

Successfully managing an efficient, profitable pasture-based system required a real sense of clarity and discipline.

There’s a need to be very clear about pasture covers, rotation lengths through the season, grazing intensity and judicious use of supplements – when you can use them and when you can’t.

It’s about being strategic and getting stocking rate right was fundamental – without that it would be difficult to deliver on other KPIs.

Horan said future improvements and areas where research should be targeted were improving animals and improving swards.

Animals – through breeding – needed to be more robust in terms of animal health, be disease resistant and have lower levels of lameness and mastitis.

Product quality in terms of milk components – healthy fats, proteins and processing characteristics were important too.

Animals that could reduce the environmental load, increase feed intake and reduce emissions would be desirable.

Pasture swards hadn’t made significant improvements over time and more effort needed to go into pastures that could produce more, high quality feed with less reliance on chemical fertilisers.