Price Pressures Flatten

While some fertiliser costs are softening, global volatility is not going away and neither are the inbuilt costs for the industry to improve its environmental footprint. Words by Sheryl Haitana.

It wasn’t a pretty primary sector picture when Whakatane-bred Kelvin Wickham returned to his roots in the Bay of Plenty to be Chief Executive of Ballance Agri-Nutrients in 2023.

He started the job amidst spiked fertiliser prices, high priced inventory stock still onhand, global freight disruptions, high interest rates, inflation and low onfarm returns affecting domestic fertiliser demand.

Fertiliser prices have softened since the 2022 peak from the Covid pandemic, but for New Zealand, fertiliser supply and prices in the future will always be dictated by these global waves, and NZ has to figure out how it floats best in the wash, Kelvin says. “On the wider scene, I think the world is going to be more volatile. The bigger countries and locations will look after themselves first, which is well within their rights. There are things we can’t control.” The Chinese put export controls on from time-to-time to focus on their own food security or India will increase subsidies to help their local farmers, which are just two factors that influence the global fertiliser price market.

The co-operative (co-op) has strong long term partnerships which help to secure supply of fertiliser products amongst global disruptions. It aims to optimise as well as it can when it comes to buying product at lower prices and smooth the peaks and troughs for its shareholders and farmers. It is a fine balance to ensure it has enough stock to meet domestic demand, and not having too much product onhand to avoid the situation it was in last year with high priced inventory stock sitting in storage.

Ballance Agri-Nutrients Head of Procurement Shane Crean says the co-op, whilst optimising to some extent like many global fertiliser buyers, was not in the position to take full advantage of lower prices in the second half of 2023 because they still had high priced inventory to sell, coupled with limited storage capacity and uncertainty surrounding future demand from customers.

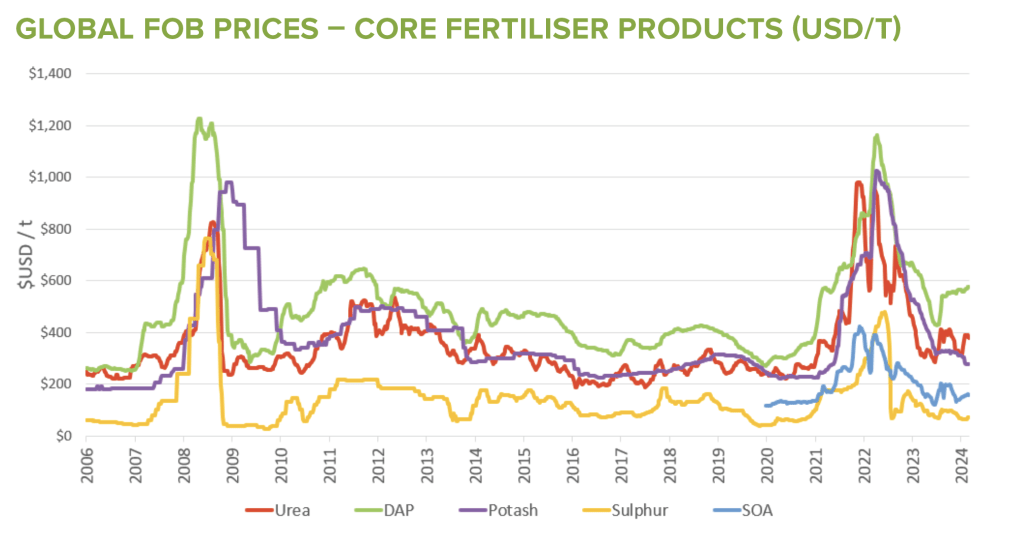

Shane joined Ballance in 2018 when fertiliser prices were softening. Disruption subsequently occurred with Covid, Belarus sanctions, and the eruption of the Russian-Ukraine War, pushing prices up to the spike seen in mid-2022. “We’ve come off that spike, but the challenge most fertiliser buyers have had around the world is that with those high prices, their customers haven’t been buying at the levels they normally would. The positive news is that we’ve exhausted those inventories, so we have been in a position to replenish our stocks with lower priced products to more normalised margins.

“We are now seeing prices flatten, or starting to firm again across many of our nutrients. We are certainly nowhere near those spikes of mid-2022, but by the same token we’ve not got back to those low prices we saw in 2020 either. For most of our nutrients, we are back at those long-term averages at the moment, and whilst there will continue to be volatility, we would expect to sit around those averages for the foreseeable future.”

Longer term forecasts are suggesting prices will continue to firm across most commodities through to 2050. “Whilst we certainly need to be cognisant of those forecasts, I take those long-term predictions with a grain of salt – I am pretty focused on the short to medium term to ensure we can purchase quality products at the best price we can for our co-op members.”

Big players are ready to buy again

Some of the things that are likely to impact pricing leading into the second half of 2024 are the seasonal buying that will start from large players around the globe, Shane says. “We are talking about the likes of USA, China, Brazil and India, and to a lesser extent Malaysia and Indonesia. These big buyers have been sitting on high inventories that are diminishing and they’re going to have to start buying again.”

Another key influence happening as Dairy Exporter went to print, were reports out of China suggesting Chinese export controls were about to be relaxed for product shipping in April and beyond. Should the controls be lifted, whilst China is still bound by export quotas, having strong relationships with Chinese manufacturers and other manufacturers around the globe will help the co-op to access volume in times of high demand over spot buyers who don’t necessarily have those strong connections.

“I’ve inherited a lot of relationships with suppliers that, in some cases, are decades old,” continues Shane. “We invest a lot of time and effort in maintaining and fostering those relationships, which allow us to access products when they might not be available to others.”

There are many global levers that can influence supply, so you need resilience in your supply chain, he says. “The more resilience we have across all our products the better. Each nutrient has quite different dynamics and influences affecting price and availability.”

Morocco has around 70% of the world’s phosphate rock reserves. Since the re-opening of New Zealand’s borders post-Covid, Shane has spent a lot of time travelling to investigate and undertake due diligence across a number of alternative sources of phosphate rock and other nutrients that could meet the needs of co-op members. As a result, he has imported products from different suppliers in South Africa, China, Australia, and Vietnam.

Closer to home, the Australian mines are changing the scene for phosphate rock supply and are set to play a key role in the Asian and Oceania markets. “Australia is a relative newcomer to producing rock,” explains Shane. “The phosphate rock is good quality and low in Cadmium and we are looking to increase the amount of Australian rock in our SSP blend.”

“We can’t source all of our phosphate requirements from Australia. Being closer to New Zealand means we don’t have to pay as much freight for shipping the Australian rock and we can ship smaller volumes more regularly. That said, despite the close proximity, it does come with supply risk as well. We saw the effects recently when the rail and road networks between Mt Isa and Townsville were impacted by Cyclone Kirrily meaning it was difficult to transport product to the coast.”

Given the high inventories it finished the last financial year with, the co-op will be conservative of how much product it buys ahead this year, Shane says. “I don’t think we will see the volumes we saw two or three years ago. We are always trying to get the best prices we can and pass those onto our cooperative members. Supply certainty and availability is important. We need to ensure we get product at the time we need it and the time our customers need it.

“NZ punches above its weight for the relatively small quantity we buy. I think our reputation as leaders in agriculture, from an efficiency and innovation perspective is appealing to our global suppliers. They look to NZ for direction on how we do things.”

Domestic pricing pressures

The future for Ballance Agri-Nutrients is a future where the company will sell less volume of fertiliser and pivot more into nutrient solutions. The cooperative is investing significant capital in research and development; technology like geospatial mapping and artificial intelligence to improve profitability and sustainability gains for farmers. Product development will also continue to play its part, says Chief Executive Kelvin Wickham.

“We have to keep working hard to be a trusted advisor; to continue to think about what we can do with innovation and move toward agritech and how we can help embrace that.” The product of the future is going to have to be a lot more precise and targeted, to deliver the right product at the right time and the right place.

“We expect to sell less volume over time, due to some of the constraints, but also because we are going to get smarter with how it’s applied. Fertiliser is a relatively small part of that footprint, however we have to do our bit. For us, it’s also how we reduce carbon in our manufacturing.”

The obvious example of that is the Kapuni urea plant, which is a great asset for New Zealand, he says. The co-op is working to transition away using natural gas in the plant to ensure NZ has one of the world’s lowest carbon footprint nitrogen sources available.

Domestically, NZ also has to contend with paying carbon tax while other countries will not have to have that same consideration around their use of product or production of it. “One of the challenges NZ faces is we have a carbon tax on our urea manufacture. At the same time we expect carbon price will firm over time.

“That means that the increasing carbon tax we pay will have to be covered somehow, but urea imports won’t have that tax. If you’re producing urea somewhere in the Middle East or Asia, you’re not subject to a carbon tax, it means you can still use gas.”

This means NZ has to find some way of becoming more efficient because we have to cover the cost of that tax. “We’re committed to support the Government’s drive to net zero by 2050,” says Kelvin. “it’s just how we all work together in terms of transition so that we can still have lower carbon footprint nitrogen for our farmers and growers and they can still be profitable.

“We need to work with the government and other industry players to come up with a good solution.”

NZ’s total agricultural outputs are probably going to decline, so the primary sector must focus on premium products to offset the increased cost of production, he says. “We are not alone in the world, we need to shape up as NZ Inc, if we want to be the first choice. The first preference. Those consumers are going to be more discerning. Track and traceability, that’s where we’ve got to play.”

NZ farmers have been successful in the past because they have been good at lifting their heads out of their business and looking outward, and Kelvin expects they will continue to come up with the solutions around farming with a lower footprint.

Listen to the podcast:

What we do in winter has a fundamental impact on the productivity of our pastures, from a persistence perspective, a soil health perspective, and from a production yield perspective. But where do you start?