Split calving, once-a-day milking and breeding the entire herd to beef is ticking all the boxes for Chris Falconer. The North Waikato farmer talked to Sheryl Haitana about farming in the sweet spot.

Chris and Sheila bought their Waerenga farm six years ago and have found a good balance on the milking platform and using the steeper hills for rearing dairy beef.

This will be the third season Chris, 48, has chosen to mate all the cows to beef rather than breeding their own dairy replacements.

The split calving, once-a-day (OAD) operation is based on simplicity and profitability. The dairy beef fits into that model well and gives them even more flexibility in their system, Chris says.

This is the third season they have not reared any of their own dairy replacements. They sell 85% of the calves at four days old and rear the rest through to 12-14 months.

Four key drivers are behind Chris’ decision to mate the entire dairy herd to beef genetics.

The first and foremost is financial. When farmers actually sit down and do the maths of rearing a dairy replacement it would surprise them, he says.

“Most people would be mortified to know the true cost is about $1800- $2000. I can buy in good three and four-year-old cows for $300 to $400 less than that.”

Farmers also have capital tied up in youngstock which is a risk as well as an opportunity cost, he says.

“I only buy in cows I need so I haven’t had to upfront the cost of 20- 25% replacements. Our empty rate is 8%, and our replacement rate is 13%. We carry 6% over between the herds so I’ve only had to buy 7% replacements this year.”

has been the beef schedule. Selling dairy beef calves in the first six weeks while most farmers are calving down dairy stock, means the market is strong.

Chris drives the four-day-old calves to the Tuakau and Frankton markets where the calves average $150-$200 with the more aesthetically appealing white-face calves selling for $400.

Once the markets get flooded with more dairy beef calves coming in, the prices drop to $70/calf and Chris stops selling and rears the rest. He usually rears about 30 or 40 from each of the spring and autumn herds and takes them through to about 12-14 months. Last year he got an average of $1180 for a rising two-year-old.

Even though they’re not all aesthetically pleasing with white face and white feet once they are fully grown buyers see them for the quality dairy beef animals they are, he says.

“We don’t try and finish them here on our hills. Buyers won’t buy them as calves but are happy to buy them to finish when they see a line of them grown. The market has more respect for them as animals rather than aesthetics.”

The third driver is they have no bobby calves onfarm, which means no animal is a waste product.

“I think bobby calves is an issue for the industry that is the closest to the truth when it comes to public perception.”

As an industry there is no point trying to defend something that is not defensible in the public eye. Instead the industry needs to find other ways to ensure there are no waste calves, he says.

Veal is a market Chris is interested in to add diversity to their business. Milk veal is a great product and would make a great seasonal product that people would look forward to, he says.

Journey to farm ownership

Chris and Sheila were previously sharemilking 350 cows for Chris’ uncle Ian Elliot at Walton before they bought their farm in 2014.

Ian, who passed away earlier this year, was a significant mentor in Chris’ life and his career in the dairy industry.

Chris didn’t grow up on a dairy farm but would spend every August holidays on Ian’s farm helping during calving.

“I was inspired to farm by my Uncle Ian. He was a teacher and mentor to me my entire life. He is greatly missed by his family, friends and the communities he supported.”

When Chris left school he studied zoology before making his way back to dairy farming. He met Sheilia, who is English, while he was travelling and the couple went contract milking then sharemilking for Ian Elliot. They then sold their herd and took a holiday/sabbatical to England where they ended up staying nine years and having their three children.

Chris managed an organic dairy farm and worked as a farm consultant before the couple bought into their own farm in an equity partnership. Chris also did a Nuffield scholarship on sustainable farming systems in 2010.

The couple soon decided the best opportunities for their children were back in NZ and shifted back in 2011. They went sharemilking again for Ian for three years to gain enough equity to buy their own farm.

The couple split-calved during their last season sharemilking to make the most of the $8.10/kg milksolids (MS) price.

In their first season as farm owners the milk price crashed, however, and they were holding on by the skin of their teeth, Chris says.

The couple are still highly leveraged, but they can generate quite a bit of cash with costs sitting about $3.20/kg MS.

“The goal is to consolidate the balance sheet now. We don’t need to get bigger, we need to reduce debt.”

They sold their Fonterra shares earlier this year and will be supplying Synlait this season.

The higher winter premiums along with other incentives, such as 8c to not feed palm kernel, was a big pull factor.

“We’ve stopped feeding palm kernel and the more expensive feed costs us 6c, but with an 8c premium we are still making money. Plus we can hold our hands up and say we are not feeding palm kernel.”

Farming a simple system

Farming a simple system

They have milked OAD and split calved for all five seasons on the farm. If the cows can average 300kg MS Chris is happy.

The choice to milk OAD throughout the season is down to a number of reasons – animal welfare, costs and labour – including total labour and labour flexibility.

The operation is set up to make it easy for one person to manage on their own.

Chris employs one other full-time staff member who averages less than 40-hour weeks.

“I give him two one-hour breaks and he’s home by 3pm most days. It’s a pretty simple system. There is not a lot of compulsory daily work, milk the cows, washdown, check the springers and feed the calves. The only job to do in the afternoon is feed the calves.”

Sheila is a cardiovascular nurse at Waikato Hospital and milking OAD has also allowed Chris to be around for the kids more in the afternoon (Hannah, 16, Oscar, 14, and Jonty, 12).

“In the tough years having a second income has also been invaluable,” he says.

Cups go on a 6.30am every day of the year and the farm dairy has excellent cow flow.

The 40-aside doesn’t have automatic cup removers but it works well, with milking the cows OAD they still have to wait for some cows, Chris says.

“Twice a year we are only milking six rows and we are finished and cleaned up in 90 minutes, tops.”

He has pulled back the operation to sit between a DairyNZ System 1 and System 2. They make hay and silage on the farm and buy in a distiller’s grain and tapioca pellet which is fed through the farm dairy.

“We use it very strategically in winter and parts of summer.”

The pellet also includes Mineral Boost which includes all the necessary minerals so they don’t have to treat troughs or dust paddocks with magnesium. They don’t have any metabolic issues and feeding in the shed also helps the springers transition better, Chris says.

Chris has moved away from cropping, and will now just spray out and regrass paddocks that need to be fixed. They use a light power harrow and direct drill and plant a standard AR37 mix.

He has also stopped using artificial fertiliser and instead is putting on chicken manure.

Their nitrogen leaching is 17kg N/ha and has gradually reduced over the last few years and they are harvesting about 11-12t DM/ha.

Effluent is spread on about 35ha with a travelling irrigator.

Mating

Chris runs a 12-week mating programme, three weeks of Artificial Breeding (AB), and nine weeks using bulls.

He uses the CRV Ambreed FertaBull short gestation semen which has three bulls in each straw.

“I like the fact there is three different bulls in each straw – that reduces the risk.”

Milking OAD and mating a bit later helps get more cows in calf. Chris uses the short gestation semen at the front of mating which is opposite to what a lot of farmers are doing.

“We get 70% conception in the first three weeks. Using short gestation gives us a bigger gap and allows us to push mating back to let the cows start cycling.”

They typically start mating around June 17 and October 23, but Chris is not fixated on the dates.

They don’t use any intervention and tail paint the day before they start AB.

That means they usually start calving about August 1 and March 20. It’s a late spring calving for the North Waikato, but on their farm the hardest months are August, February and March, Chris says.

When it comes to buying their dairy replacements there are plenty of great quality cows out there who just need better management to get in calf, Chris says.

“I like to think there are plenty of good cows out there that don’t get in-calf through management and no fault of their own.”

He only buys two, three and four-year-old cows from a supplier who buys empty cows and gets them in-calf.

“I don’t like big cows. I look for good udder attachment, teat placement and big briskets.

“If there is an opportunity to buy a higher BW cow I’ll buy it. I’m getting the benefit of other people’s work.”

The last line of cows he bought had a 110 BW and 130 PW average.

“Disease is a concern. But we don’t buy from Dick, Tom and Harry. I spend a lot of time and effort being careful who we buy from – from good systems, talking to the vets, making sure we have certification.”

He buys Hereford bulls off the farmers behind him. He buys six two-year old bulls each year which cover the autumn and spring herds.

He sells them the following year and each bull usually only costs him about $200/bull.

Having a flexible system means they can react to the market and what the season is doing.

“We can react and respond to the what’s infront of us.”

If they are short of grass for example they can sell the dairy beef animals on the farm, or if the market strengthens they can sell them.

“Our stocking rate is conservative (2.3cows/ha) so we don’t usually have to sell into a market that’s not agreeable.”

The dairy beef calves are an easy class of stock to manage, he says. They’re strong, independent and grow well.

He feeds the calves about 1kg meal for three or four weeks after mating along with hay all the way through. He keeps them on the milking platform until they’re six months old and ready to go up to the hills.

The highest point of the farm is 190 metres above sea level while the cowshed is down at 30m.

The farm has about 35ha of bush and the 30ha tougher terrain that they use to rear the dairy beef animals. They also graze the dry cows from each herd on the hills for about four weeks for each herd.

The longest walk to the farm dairy is 2.5km on the milking platform, while it’s 4.5km out to the back of the drystock block.

The race has been well built and it’s not a hilly walk for the cows, Chris says.

Chris and Sheila have planted about 5000 plants themselves and have another 12ha they want to plant. Chris is also hopeful they can gift a significant ridge back to Tainui which connects with the Whangamarino Wetlands.

FARM FACTS

Owners: Chris and Sheila Falconer

Location: Te Kauwhata

Area: 255ha (195ha milking platform)

Cows: Peak 480 crossbreds

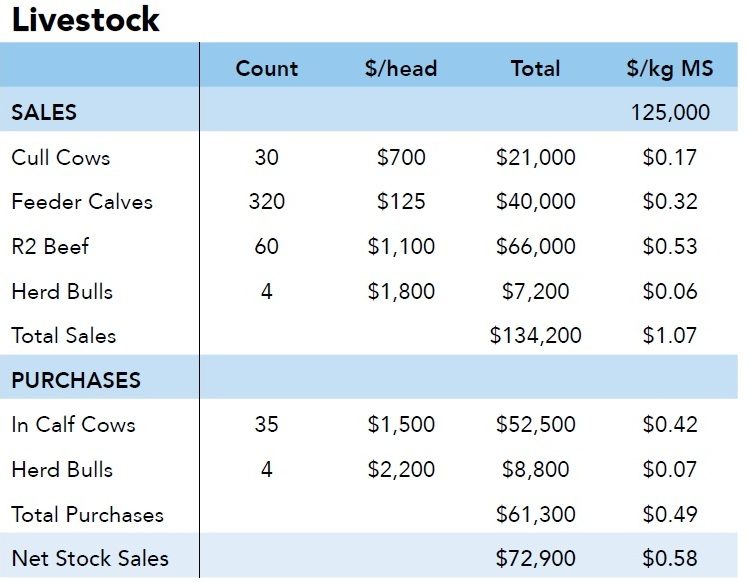

Production: 130,000kg MS

Farm dairy: 40-aside herringbone

Supplement: 180 round bales hay, 270 bales silage

Farm working expenses: $3/kg MS

Equity/debt ratio: 29:71

Winter milking adds $0.65/kg MSto GFI