Taking Dipton to carbon neutrality

Dipton’s catchment group has looked at possible ways to reduce farm greenhouse gas emissions, questioned existing farm practices, and helped gain more knowledge about carbon sequestration. By Anne Lee.

One of Thriving Southland’s 35 catchment groups has taken on the bold challenge of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

One of Thriving Southland’s 35 catchment groups has taken on the bold challenge of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The greater Dipton catchment group was formed about three years ago and after an initial, very-well-attended meeting to gauge interest for a catchment group, has run several smaller events such as farm visits, recycling workshops and community get-togethers.

Dairy farmer Charleen Withy explained that last year, after discussing key concerns among farmers in the area the group decided to tackle a GHG project they dubbed Carbon Neutral Dipton.

“We came up with that as an aspirational title.

“The aim was to focus on farm GHGs and see if they could be reduced by changing or tweaking farming systems, introducing different types of farm systems or utilising different technology.

“We also wanted to see what happened to farm profitability with the changes,” she told the SIDE workshop in Invercargill this year.

At the time there had been a lot of discussion around the emissions trading scheme (ETS) and the farming sector’s proposal on pricing emissions, He Waka Eke Noa (HWEN).

“As farmers we thought it was a good opportunity to increase our knowledge on those things and carbon sequestration and then share that with the community.

“As a committee we all had varying degrees of knowledge on how it related to our farms – plus there were the changing goalposts of the pricing of the levy on farmers.

“We thought this made it important to front-foot it and investigate it ourselves as farmers to see how possible changes to our onfarm emissions would impact our bottom line,” she says.

Five farms in the district became the case study farms – two dairy farms and three sheep and beef. They were chosen as a fair representation of the Dipton area and included farms on both hill country and flat land, she says.

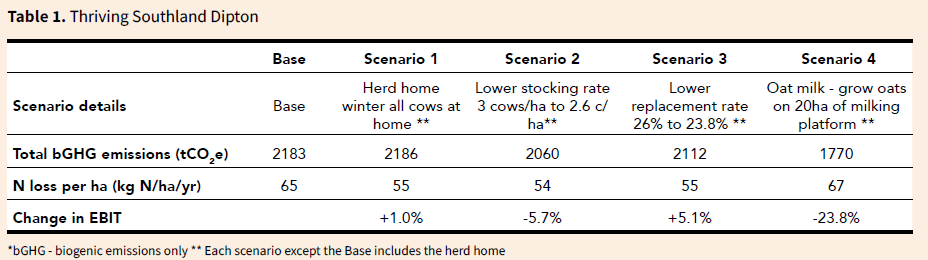

Funding through Thriving Southland enabled a farm consultant to assess four to five farm system scenarios on each farm, modelling them through both OverseerFM and Farmax. Total GHG emission losses, nitrogen losses and farm profitability were modelled with each farm coming up with their own specific scenarios.

A forestry and sequestration analysis was carried out, too, providing farmers with a report that detailed the types of plantings, costs and income from the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS).

Buddy farmers joined with the study farmers and consultants to thrash out a range of possible farm system changes to model, Charleen says.

“Having buddy farmers was a great idea to bring in more perspectives,” she says.

In their case, Southland farmers Stefan and Annalize Du Plessis, Louis and Angela English and Rex Kane were the buddy farmers.

A community meeting was also held to get even more input and ideas.

Charleen farms with her husband Chris on 156ha (143ha effective) peak milking 440 Friesian cross cows.

Their status quo, baseline situation for the study was:

Production: 440kg milksolids (MS)/cow.

Supplement: 147 tonnes palm kernel (334kg/cow) to fill deficits and 100t drymatter (DM) bought-in silage (227kg DM/cow).

Farm dairy: 36-aside herringbone with in-shed feeding.

Wintering: Most of herd wintered off. About 65 mixed-age cows are kept at home on fodder beet through the winter.

Replacements: 115 heifers grazed off- farm from 100kg liveweight.

The farm has three different soil types – Lumsden shallow, Makarewa deep and Pukemutu.

A one-hectare pine tree block is used in spring as a stand-off area during wet periods to protect the milking platform soils and pasture. In the base comparison year they made 70t DM baleage onfarm and grew 30t of oats.

Effluent is spread over 58ha.

Charleen says a hypothetical runoff was included so it could be modelled enabling the whole farm business to be encompassed in the study.

The four scenarios chosen to be modelled were:

- A herd home to allow all cows to be wintered at home.

- Lower stocking rate from 3 cows/ha to 2.86 cows/ha and reduce imported supplement plus herd home.

- Lower heifer replacement rate from 26% to 23.8%, modelling this on the hypothetical support block plus herd home.

- Have 20% of platform in oats for oat milk and the stocking rate reduced accordingly plus herd home.

The results of the modelling showed little reduction in GHG emissions unless there was a significant drop in animal numbers.

The oat milk scenario removed 20ha from the milking platform and while it made the most significant cut to GHG emissions (19%) it came with an even bigger cut in profitability (24%).

Charleen says they looked at the oats option because a previous study has investigated it in Southland.

While growing oats ticked the box in terms of GHG emissions reductions, the cultivation used in the modelled scenario on their farm meant nitrogen loss reductions weren’t achieved either. It shows just how important it is to look at any system change with an eye to a range of factors rather than having a blinkered or tunnel-vision approach, only focused on the effects on one outcome.

She and Chris had already carried out analysis on putting in a herd home for wintering purposes and have gone ahead with that scenario.

While it doesn’t do anything to reduce emissions on its own, it may allow them to make better use of new feed additive technologies.

“Maybe our farming business could benefit from methane inhibitors being added to the cows’ diet once they become available.”

The Withys also have in-shed feeding in the farm dairy that could be used in the same way to administer a feed additive based methane inhibitor.

The study has improved understanding of what drives GHG emissions and that currently the only big lever available to farmers is drymatter intake and stock numbers.

While the lower stocking rate scenario cut GHG emissions by 5% and nitrogen loss by 17%, it also meant a 6% reduction in profit.

Lowering the replacement rate – cutting it from 26% to 23.8% – gave the best overall outcomes, boosting profitability by 5%, cutting nitrogen loss by 15% and giving a small, (3%) reduction in GHG emissions.

Combining scenarios such as lowering the replacement rate with the herd home may offer much better opportunities in GHG reductions and profit protection. There’s also a proviso with cutting the milking platform stocking rate with the possibility of greater difficulty in managing pasture well.

It can mean achieving target residuals is a lot harder through grazing alone which in turn could lead to flow-on effects on poor quality feed intake.

In the Withys’ situation the forestry and sequestration options were limited in terms of the financial returns versus reductions in income if land was taken out of the dairy platform, but a detailed report shows the costs of planting various forest species and ETS returns.

Charlene says the overall Carbon Neutral Dipton project is relatable to farmers, practical and farmer driven.

“It’s helped create conversations. It’s looked at possible ways to reduce our farm GHGs, questioned our existing farm practices, and helped us gain more knowledge about carbon sequestration.

“It’s given me a greater knowledge and understanding of my farming business and how farm systems influence emissions.

“It’s created lots of discussion and debate about wintering systems, stocking rate, heifer replacement numbers and efficient use of supplements.

“The scenarios are only models and no doubt there are limitations to the assessment tools, but they have provided a good starting point for farmers to maybe think about changes to farming systems and at the very least build up a better knowledge of farm GHG and the influence they have on farming practices.

“Who knows where the goal posts will end up regarding GHG and the pricing levy but I believe this project will benefit farmers and the agricultural industry to become more knowledgeable and not be uneasy around conversations around farm GHG.”