Anne Lee

Greg and Rachel Roadley have a very clear strategy that’s enabled them to leverage and grow their business – it’s a strategy centred on and driven by pasture.

Greg and Rachel Roadley have a very clear strategy that’s enabled them to leverage and grow their business – it’s a strategy centred on and driven by pasture.

“Rachel and I have a very clear focus – to drive high free cashflow. That’s the cornerstone philosophy for our business and it’s off the back of low-cost, pasture-fed dairy production,” Greg says.

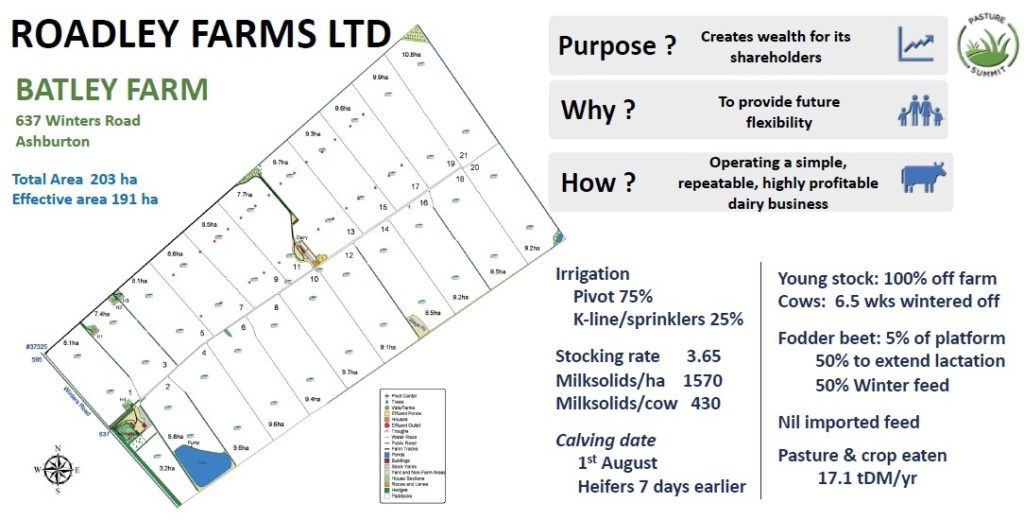

The pair opened up their Canterbury farm last month at the Pasture Summit field day sharing their data and systems approach with close to 400 people.

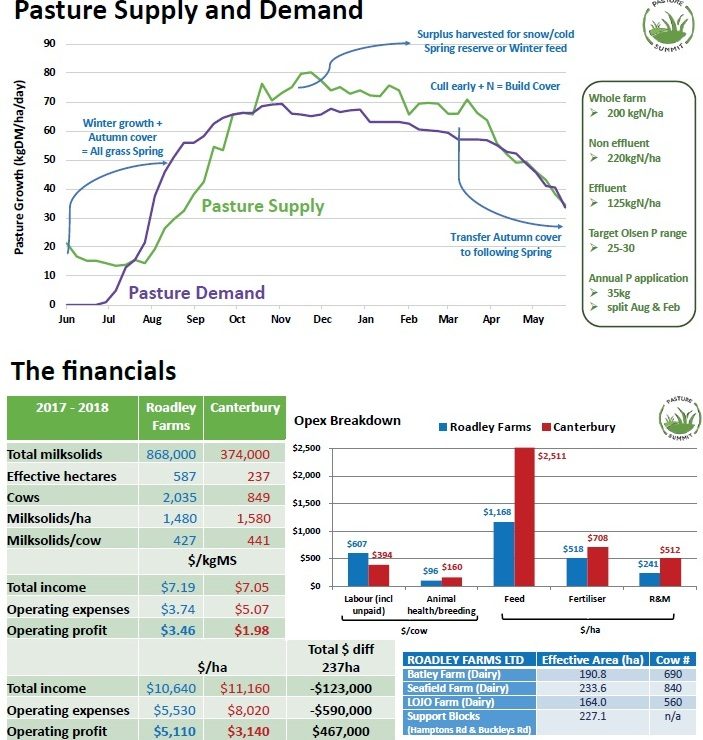

And it’s impressive with the pair managing to outstrip the average Canterbury operating profit benchmark by $2000/ha with no imported feed.

For the 2017-18 season operating profit for Roadley Farms was $5110/ha.

“We’re running a low-cost, high free cashflow business which allows us to scale and grow our business.

“We also have aspirations around equity growth and for requirements on our time – so system simplicity is a fundamental component of our business,” Greg says.

There’s no arguing with how successful the approach has been in growing the business.

From starting out working in the family operation at Dromore, just north of Ashburton, Greg and Rachel’s Roadley Farms now owns three dairy farms and support blocks and the couple are shareholders in an equity partnership that includes current and former staff.

That partnership owns two dairy farms and all up the operations milk 3100 cows.

Greg says in their earlier years they were using about 300-400kg drymatter (DM)/cow of bought in feed but as they really began to drill down into what drives profitability, they could see the pasture eaten and cost of production had the biggest influence.

Being brave enough to take bought-in feed out altogether can be a tough ask.

“We didn’t make wild swings – we gradually ratcheted back and as we did that we grew our skills in utilising more grass.

“The more you practice something the better you get at it.

“As a team we talk about trusting grass – that’s the thing about systems change – trusting the science and for us trusting the grass to deliver, and it does.

“Operating as a no (bought-in feed) input system – it’s sometimes a matter of being comfortable at being a little uncomfortable.

“For a lot of people, the biggest fear is running out of feed for your cows.

“That can be an uneasy feeling but it’s a matter of trusting your budgeting and your system and your planning to see you through,” Greg says.

Production is not the focus – conversations within the farm teams and with Greg and Rachel are all about pasture key performance indicators (KPIs).

Cost control, too, while always on the couple’s radar is also well understood by the team and built into the farm culture.

“I couldn’t tell you today what the cows are doing but I can tell you what the pasture cover is.

“In the benchmark information we collect we don’t ask the team for daily or weekly cow production.

“The farm managers know that when I talk to them off the back of the motorbike, I’m going to be asking about pre-graze covers and residuals.”

Greg will track production at a higher level across the business but he doesn’t make decisions day-to-day based on milk production.

Autumn is a key period in the calendar because it’s where the farm system is set up for the next season.

The aim is to have average pasture cover at 2000kg DM/ha at dry-off at the end of May so they can start the spring with 2700kg DM/ha as an average cover.

To get to that dry-off target they manage the demand side of the equation, culling cows early based on pregnancy tests and body conditions score.

“We start thinking about our spring feed budgeting in February and by the end of February, early March we start culling.”

Cows go on to once-a-day (OAD) milking based on body condition score (BCS) and calving date with those factors and feed supply also determining when groups are dried off.

Going into spring, the spring rotation planner is the essential tool along with very closely measuring and monitoring average pasture covers.

The feed budgets are set up based on an average season with calving data used to estimate demand.

Managers allocate pasture on a square metre per cow basis each day.

As the season moves closer to balance date when pasture demand and supply match the average pasture cover for the farm becomes a critical target.

The aim is to get to 2050kg DM/ha at balance date, Greg says.

Managing feed supply and demand over that period with no bought-in feed takes disciplined monitoring with the whole farm walked and paddock covers assessed weekly from August 1 but every five or six days as balance date gets closer.

The team uses visual assessment to estimate covers and back calculates based on what the cows are doing to confirm the assessment.

Every team member is trained and very capable at that, Greg says.

The farms all have an emergency, snow store of supplement as balage, conserved onfarm during any surplus growth.

“We have about 80kg DM/cow on hand as an emergency but as the spring goes on the teams know that if for some reason, the season for instance meant they got into a situation where cows were having to graze below the target residual of 1500kg DM/ha they can feed that back in.”

In some seasons they’ve fed 20-30kg DM/cow.

They also use nitrogen, applying it at low rates through spring once soil temperatures are steadily rising.

They keep within a 200kg N/ha self-imposed limit.

From balance date to the start of autumn they’re aiming for a round length of 21-22 days.

All of the pasture cover data is loaded into an online feed wedge tool with the pre-graze target cover of 2800-2900kg DM/ha.

It’s simple to see a looming surplus and the Greg says the aim is to act and act quickly to maximise pasture quality.

He has the view they’re farming ryegrass and using the cows to harvest that to turn into milk for sale so the aim is to do what’s right for the ryegrass while keeping cows fed well.

“If for some reason we don’t get the residual right – if it’s not quite hit – the cows will go back in and do that job.

“But they’ll be monitored closely and moved on straight away.

“We don’t pre or post graze mow. The only time we mow is to take silage because of a surplus.”

Mating performance is better than the Canterbury average with 72% six-week in-calf rate and 10% empty.

Grass is enough for good animal performance but it’s in how its managed.

Greg says just like spring pasture management preparation for mating starts right back in February with BCS targets looked at then to give plenty of time for gradual adjustments to be made.

“We want to have more cows at a BCS at the end of the season that means we don’t have to do too much to lift them with feeding through the winter.

“Winter feeding is expensive.

“Having cows fit and not fat in spring is important too from an animal health perspective and we’ll manage and monitor mobs, drafting obsessively to get that right.

“It takes work but it pays big dividends.”

He’s targeting 4.8-5 at calving – with no cows under 4.8 but no cows over 5.5 either.

Managing costs is the other big driver of operating profit.

“An accountant told me years ago that farm expenses should be 50% of gross farm income and that’s our objective – to double every operating dollar we spend.

“We try and drive farm working expenses of $3.30 to $3.40/kg MS.

“That means we rigorously interrogate every dollar of spend to make sure it’s giving us that return.”

On a per-hectare income basis Roadley farms earns less than the average Canterbury farm but their operating expenses are $2500/ha less.

“We’re passionate about farming and love the farming lifestyle but pretty ruthless in our view of it as a business.”

Feed costs are less than half those of the average Canterbury farm at $1168/ha.

The feed costs are associated with wintering cows off and young stock grazing because even though they’re carried out on owned support blocks each farming entity and support block is enterprised with its own accounts.

Repairs and maintenance, at $241/ha, is also less than half the Canterbury average with very little in the way of machinery onfarm.

“We don’t have a lot of wheels and rollers or bearings.

“There’s not a lot of gear that can wear out or rust here.”

Animal health is $96/cow compared with $160 for the regional average.

“We will review any interventions and be critical – we challenge them hard.”

They make sure businesses and professionals working with them are aligned with their way of thinking too so they’re not constantly batting away salespeople or being pushed to adopt expensive programmes.

“We also focus on excellence with team – they’re skilled and understand livestock so that gives us a preventative approach rather than having to fix a problem.”

Greg says on any given day he has 100 ideas going through his head on how to drive the business more efficiently and more cheaply.

Greg says on any given day he has 100 ideas going through his head on how to drive the business more efficiently and more cheaply.

“We didn’t coin the phrase but using innovation to beat inflation – is our philosophy.

“We also try to operate on the steepest part of the return curve given most things have a diminishing marginal return.”

The one place they do spend more than the average is on labour – at $607/cow compared with the regional average of $394/cow.

“We understand people capability is key driver for our business.

“It’s clear to us that profit and our costs are linked with the ability of people to run the farm in combination with the system we have.

“We make sure we’re meeting the market for remuneration – we don’t over-pay but we do meet the market,” he says.

They use contract milkers on some farms and make sure they’re aligned with their approach to ensure they’re not focused on production as a driver for their own business.

“Making sure we are running a very profitable business means we can set their rate so their only avenue to get a good return is production.”

Both the alignment, profitability and skills in running the low cost, pasture focused system have been key in the couple’s growth opportunities too.

They’ve built lifelong relationships with key team members who have gone on to become business partners and replicate the system.

From an environmental perspective the farm has a lighter footprint than the average for the region too.

Nitrogen leaching is 40% below the average of a Canterbury study group.

A lower nitrogen surplus also has an effect on greenhouse gas emissions with the farms’ emissions at 14.1 tonnes CO2 equivalent compared with 17.6 for the Canterbury average.

That’s driven largely by reduced feed inputs.

“It’s heartening to see that this kind of system can have lower-than-average losses but higher-than-average profit.

“I think solutions are coming so we’re watching and picking up the science and best practice as it’s proven.

“Nitrogen is a valuable input into our system so if we’re leaking it we’re losing value – we know there’s a link with any leakage out of system and profit.”

This article is free to view because it is a topic of high importance. This article was published in New Zealand Dairy Exporter magazine. For less than $10/month, you can receive this detailed information to help improve performance within your business. nzfarmlife.co.nz/country-wide/

Supporting New Zealand journalism.