What the cow wants

Researchers have taken a look at dairy farming from the cows’ perspective. By Elaine Fisher

If cows had a say in the design of dairy farms they would want smaller herd sizes, more time with their calves, more shade and shelter, reduced walking distances and choice of milking times.

These are among the conclusions 12 New Zealand dairy farmers came to after taking part in AgResearch workshops which posed the question: “If you were a cow, what would you want?”

Instead of being regarded as part of the production system, the researchers took the view that cows are also key dairy industry stakeholders.

Those involved in the research were AgResearch senior scientist Gosia Zobel; Katelyn Mills, AgResearch, Penny Payne of AgResearch and University of Waikato, Environmental Research Institute and Katie Saunders, DairyNZ.

Gosia, lead scientist for the research, says it didn’t take long for the five men and seven women taking part in the study to think from a cow’s perspective.

“Everyone was quite enthusiastic about the idea, especially when we explained why they were being asked to do it and that they’d get the opportunity to physically ‘build’ (using photos) a future system. It’s a novel way to collect ideas that no one had experienced before.”

Access to cooling options such as man-made ponds, varied foraging, portable parlours or conveyor systems that reduce long walking distances, and environmental enrichments with opportunities to promote scratching were also on the ‘wish-list’.

End-of-life considerations were important, with the suggestion of a mobile abattoir onfarm to eliminate transport stress.

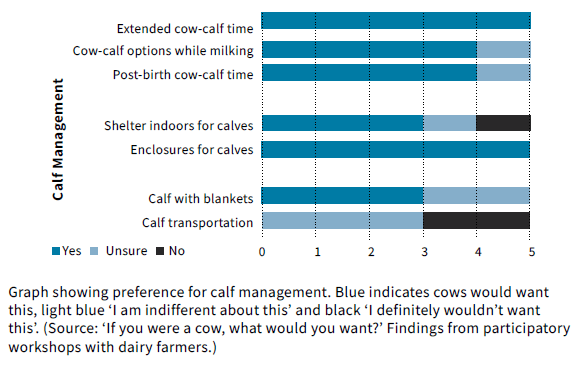

When it came to calf management, most participants were in favour of cow-calf contact systems. Among the comments was: “If I was a mother, yeah I’d want to keep my kid around as long as I possibly can”.

Participants also felt that it was necessary to consider the frequency of calving to manage surplus calves as reflected in this comment: “I’m still personally not sure that there’s a place for all those calves no matter what we do. But we did talk otherwise about potentially slowing down that cycle because if cows were under less pressure [to] get in calf or just had a calf every 18 months then you would have less calves and maybe then you wouldn’t need your bobby calves”.

Breeding practices resulted in conflicting opinions. Some groups were against artificial insemination: “I wouldn’t want a big guy with a big fat arm, AI…I’d be like hell, no”; whereas others believed it was preferable to natural breeding by bulls; “You seen a bull….? They’re not always nice and they don’t ask permission.”

Herd sizes of under 200 cows would be preferable, with none of the participants preferring herds of more than 500 cows. They cited decreased care and farmer attention as farms increase in size. Among the comments were: “Not 1000, I want to be known and noticed…”

“Depends on how many people there are helping us. Like smaller the better really.”

“I would pick 200. It’s got enough scale that there’s probably two sets of eyes on you.”

Participants talked about social grouping and social stress with one farmer saying: “the bigger the herd, the more social stress they have because they find it really hard to find their friends… If you had 1000 cows in one herd it would be very stressful”.

The groups discussed technological solutions to move cows to the cowshed without the need to walk long distances and among the ideas were canals with floating platforms or conveyor belts. Comments included: “As a kid I used to dream my races were a big conveyor belt.”

“Yes, I’ve had the same thought.”

“It’d be fricken awesome if you could do that. You would eliminate walking.”

Gosia says the aim of the study was to have farmers take the perspective of the cow, and by trying to think like a cow, draw out farm elements essential to creating a cow-centric dairy system. The farmers were also asked how this system could be achieved in the next 50 years. In the workshops, participatory methods including photo elicitation and timelining were used to generate discussion.

“Pasture access is frequently cited as an integral component for promoting good welfare in dairy cows, so this cohort of farmers was considered a good case study as they all had experience managing cows in grazing systems.”

Those taking part in the study were a mix of owners, sharemilkers and managers. They all worked onfarm, day-to-day with animals, had an interest in promoting good animal welfare and had been involved in other DairyNZ initiatives.

“Farmers work daily with their animals and have a deep appreciation of how cows respond to different situations, and therefore they also have good insight into what may be best for the cow. The idea is that if dairy systems are to continue to evolve as they have been for decades, it is instrumental to have farmer input,” Gosia says.

“This study gave us a unique insight into how future farms might be designed if we thought about them from the animals’ points of view. The results will help us focus on specific farm design and management options, as we identified both ‘low-hanging fruit’ and more future-focused opportunities. We can study the impact the identified opportunities might have on cows’ experience and overall welfare, while keeping in mind how these might impact the farmers as well.

“While this was a small exploratory study, it has provided a foundation for informing our on-farm research, and for what questions need to be asked and addressed within the dairy industry as a whole.

“There is immense value garnered from the way we undertook these farmer discussions. For instance, even though the research team had an overarching aim of understanding how technology can help with the development of future farm systems, the participants identified many options that cows might value that were not technological.

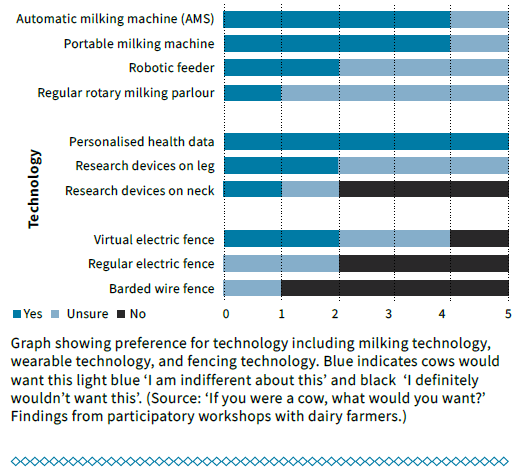

“Participants also led useful discussions on the pros and cons of using technology. They picked up on some key characteristics that they felt would make the difference between a cow benefitting from a technology, like the weight of a device or if it replaced farmer-cow contact, or not.”

One goal of the on-going research is to determine if sensors can be used to understand how cows are experiencing different situations onfarm, as this can tell if they are living a good life.

“Getting a deeper understanding of what good farm design might look like from the cow’s perspective helps identify the role of technology in delivering more ‘cow-centric’ future farms.

“When examining such a big question, we aim to involve the key stakeholders, which includes the cows and the farmers. To support our understanding of what good looks like from the cow’s perspective, we have a few ongoing studies collecting behavioural data using technologies, and we are also bringing in supporting science from around the world.

“We think our approach of considering the cow’s perspective and using photos helped encourage these frank discussions; such insights are likely easier when a person is given free rein to be creative and ‘think like a cow’,” Gosia says.