Farm environment plans with an added GHG module will help farmers start to understand what drives emissions on their farm so actions can be taken to reduce the levels, Anne Lee says.

By the end of this year a quarter of all farmers – dairy, sheep and beef – will need to know what their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are and have a written plan for how they are going to manage them.

Within four years 100% of farmers will have a written plan according to the programme being developed by He Waka Eke Noa – the government/primary sector climate action partnership.

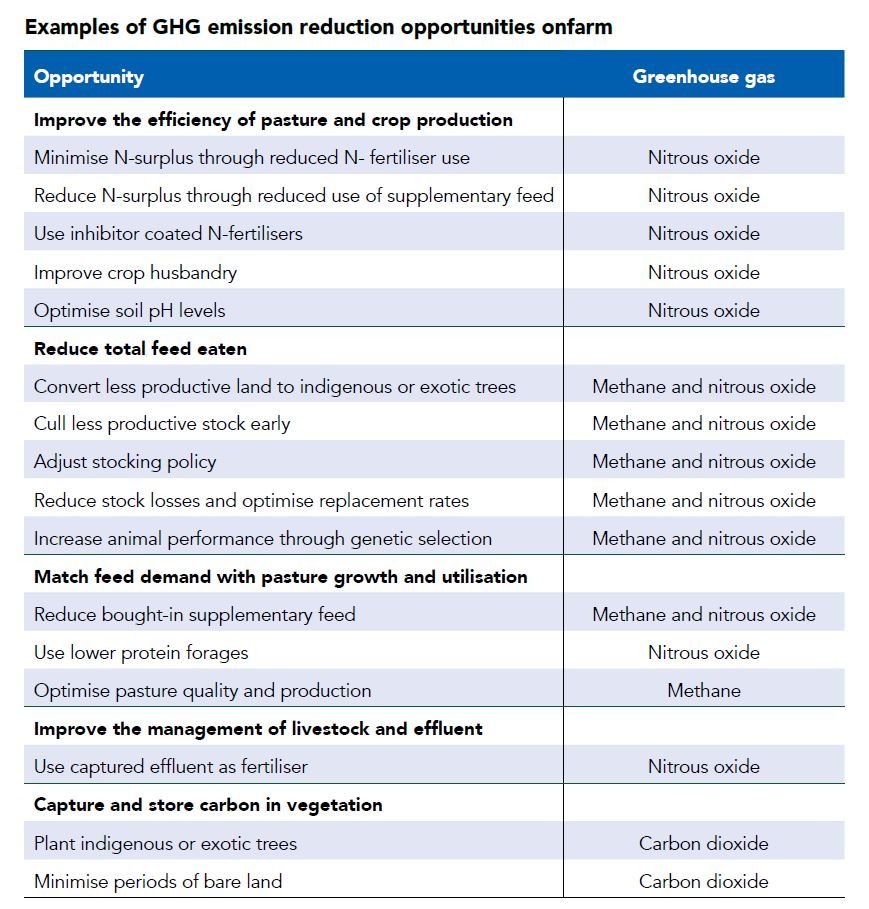

Dairy farmers were already expected to have a farm environment plan by 2025 to meet the requirements in the National Environmental Standards and Essential Freshwater Management rules, but now they’ll need to have a GHG module in the plan as well. The overall goal is to get New Zealand’s onfarm methane emissions down by 10% by 2025 and work towards a 24-47% cut by 2050. He Waka Eke Noa has just released its GHG farm planning guidance to the sector for review, with the next edition due out in March. DairyNZ farm business specialist Sarah Dirks works on the Step Change project – a project to help farmers reduce their environmental footprint while improving profitability.

“Reducing GHG emissions is an important part of that along with other water quality factors such as managing nitrogen loss, and we know that in a farm system it is important to look at each carefully but also with the others in mind,” she says.

The good news is that in most instances taking action to reduce one will help the other, but there are some exceptions.

One of the first goals is to ensure farmers have an estimate of what their GHG emissions are and provide them with a benchmark so they can see how efficient they are compared with others.

OverseerFM provides an emissions number and many dairy companies are also providing farmers with a GHG emissions report.

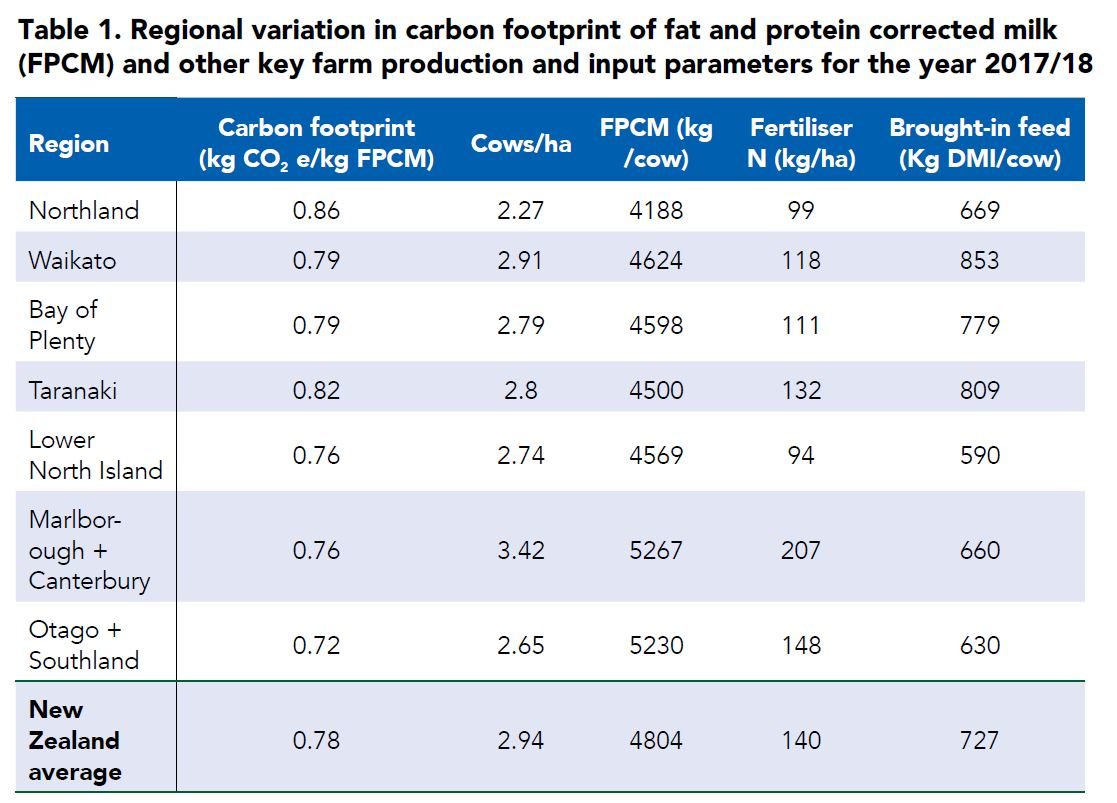

Table 1 gives an indication of regional differences and is taken from a research study published in the Journal of Dairy Science in 2019.

Sarah says it’s important for farmers to take notice of the units used when comparing or assessing numbers – some may be tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 e) and some in kilograms, some may be for total emissions for the farm and some may be per hectare or per cow, per kilogram of milksolids (MS) or, as in table 1, per kg of fat and protein corrected milk. Fonterra’s report gives farmers a comparison with other farms in their region that are producing milk at a similar per hectare level.

The new GHG modules likely to be included in farm plans will have a slightly different focus compared with previous plans.

“They’ve tended to be quite task-focused – where farmers write down the actions they’re going to take over a set time period.

“Things like putting a bund on a bridge to stop sediment or effluent getting into a waterway, or increasing effluent storage.

“With GHG emissions it will include factors that are more systems-focused.”

There aren’t any silver bullet technologies available to farmers yet, although rumen modifiers and feed additives are being investigated.

‘Optimising’ the farm system is likely to be the most obvious course of action to match feed demand with homegrown supply more closely.

That’s not to say higher input farmers can’t continue that system, but a pricing mechanism could mean farmers who don’t reduce their emissions will face an extra cost.

“Methane is the biggest contributor to GHG emissions onfarm and we know it’s driven by the amount of feed eaten,” Sarah says.

That makes feed the biggest lever farmers have available to them.

“For many farmers there are likely to be improvements they can make in utilising pasture and altering supplement use that will give them efficiencies.

“With slightly fewer cows they could produce the same amount of milk with much less bought-in supplement, but they do have to look at it from a whole farm system point of view.”

Every farm will be different, as will each farmer’s situation, so the plans have to be written accordingly. Reducing total feed eaten could mean utilising pasture better and cutting supplement and retaining cow numbers, or it could mean improving reproductive performance so fewer replacements need to be reared.

It could also be culling cows earlier in autumn to limit the need for autumn supplement.

Cutting fertiliser nitrogen inputs could help limit nitrous oxide losses and methane emissions if less feed is grown and consumed by cows.

“The important thing is to start understanding what drives emissions and more specifically what drives your farm’s emissions so you can tailor actions to that situation,” Sarah says.

It’s clear from the recently released Climate Change Commission report that the changes farmers have been making in an effort to improve water quality aren’t going to enable agricultural emissions targets to be met on their own. Nitrous oxide emissions make up a smaller percentage of farm emissions, but it is a much more potent GHG. It’s released into the atmosphere from dung and urine patches and nitrogen fertiliser.

Fertiliser companies now offer coated urea products that inhibit the release of nitrous oxide, and switching to these products could be a simple action farmers can take. Sarah says DairyNZ will continue working with the industry and regional councils to help them set up farm environment planning to align freshwater and GHG farm planning, and the new guidance will help in developing the GHG emissions sections in the plans.

To date most farmers have had rural professionals help prepare their farm plans with them and its likely that will also be the case for the GHG section, particularly as some farmers will choose to reassess their whole farm system.

That needs careful analysis to ensure profitability is maintained and a change in system will actually achieve the reductions in GHG aimed for.

“A change in farm system certainly won’t be the right thing for everyone. Some farmers are already highly efficient and have limited options.

“There will always be some area for improvement and that’s where we have to start.

“It is still not clear which farmers these targets will affect the most, but farmers do need to start thinking about what they’re doing with their GHG emissions in mind.”

As with farm plans aimed at improving water quality, farmers will need to keep good records to show what actions they’ve taken when it comes to audit time. In many cases the changes will be reflected in their OverseerFM and GHG emissions reports.

To calculate emissions the minimum information required is:

- Livestock numbers by stock type and age group.

- Amount of synthetic nitrogen fertiliser applied annually.

Other information required to give a more detailed understanding of the farm’s emissions and reduction opportunities include:

- Farm total and effective area

- Farm topography

- Livestock class, age, number and movements

- Nitrogen fertiliser or lime applications including product type, rate and timing

- Production data such as milksolids, liveweight, or crop yield

- Woody vegetation planting records.

Work is under way within He Waka Eke Noa looking at carbon sequestration opportunities so that farm plantings in areas such as riparian strips may be able to be included in emissions calculations.

Sarah says a farm environment plan is a positive step for any farm business and shouldn’t just be seen as a matter of compliance.

They can be a powerful tool from a strategic business planning point of view and promote further business analysis that will benefit the operation in a financial and strategic way, she says.