It’s all about the pasture

A focus on pasture first, keeping costs low and driving profits through strong cashflow means a dairy operation has been able to grow not only their own business but partner with others to help grow theirs. Anne Lee reports.

At this time of the year one of the main topics of conversation on farms around the country is what cows peaked at or what production’s doing compared with last season. Not so on Roadley Farms.

The conversation – no matter what time of the season – goes straight to pasture.

“I don’t turn up and ask managers what their per cow is – that’s just not what we’re interested in.

“We’re more likely to get straight into a discussion about what’s happening with pre-graze (covers), what’s happening with residuals.

“I’ll have an eye on what the trajectory is with milk flow but that’s not what the guys are looking at every day, they’re looking at what’s going on in the paddock. We just don’t have a production focus,” Greg Roadley says.

Greg and Rachel Roadley own three dairy farms and support blocks north east of Ashburton and are shareholders in an equity partnership that includes current and former staff.

That partnership owns two dairy farms – one that’s close to their own farms and one just north of Oamaru.

All-up the operations milk 3100 cows.

Greg is speaking at the Pasture Summit later this month – www.pasturesummit.co.nz

The couple’s ethos of being pasture farmers first and foremost, keeping costs low and driving profits through strong cashflow means they’ve been able to grow not only their own business but partner with others to help grow theirs.

Their Canterbury equity partnership Winters Farm is in its 7th season and is run with real disciplines around return expectations, costs and delivering for shareholders. Greg says at the outset with any partnership it’s imperative to make sure everyone is strongly aligned in values and that expectations for the business are well understood.

They have a clear understanding of the delineation between governance and management something Rachel says has come from Greg’s involvement as a director over the years on large scale Canterbury, Southland and United States dairy farming company Grasslands.

Greg says their equity partnership farms follow the Roadley philosophy which is to focus on maximising the margin on each kilogram of milksolids by running a simple, low-cost, pasture business.

“That drives a high profit that then allows us the free cash to improve the equity position and grow.

“But each growth step is taken on the basis of thorough analysis and expectation for return on capital – so we aren’t just growing for growth’s sake, we are growing because we can grow the share price,” he says.

Greg and Rachel’s philosophy lies in understanding that New Zealand’s competitive advantage is in the ability to grow perennial ryegrass cheaply and harvest it at a low cost through a dairy cow.

‘I’ll have an eye on what the trajectory is with milk flow but that’s not what the guys are looking at every day, they’re looking at what’s going on in the paddock.’

“We try and focus on a simple, repeatable system, something that can be articulated in a quarter of an hour to someone who doesn’t know anything about grass farming.

“I think that’s what’s allowed us to scale – we don’t have the complexity – we’ve got a farming system that’s all grass so there’s not a lot of levers and places to deviate from a simple plan.”

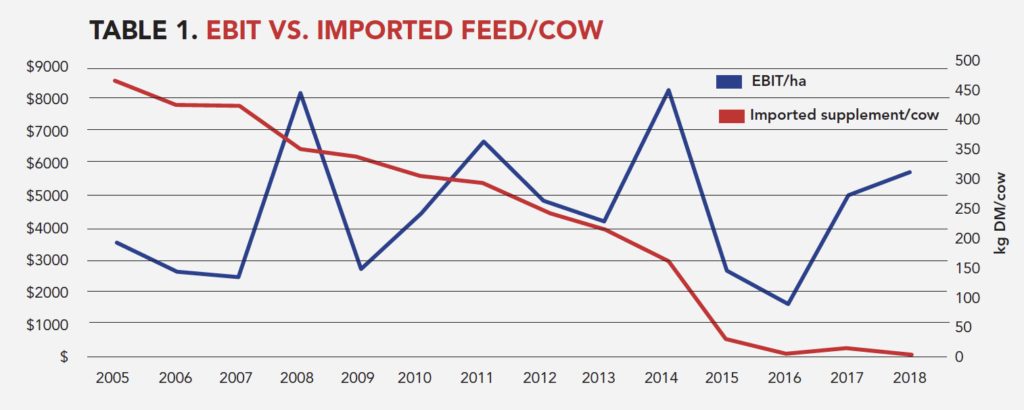

The couple’s propensity to analyse and monitor both their financial and physical data closely is what led them to pull bought-in fed out of their system altogether.

“What we have done really well since we started is monitor and measure our farming system and, because we’ve analysed that, we really understand what the profit drivers are for our business.

“We’ve learned what does and doesn’t drive EBIT for our business.

“Bought-in feed has a zero to negative correlation with profit for our business and that’s effectively driven supplement out,” he says.

As Rachel says they weren’t feeding high levels of bought-in feed – about 300-350kg drymatter (DM)/cow but they tried several types of feed and growing it themselves on support blocks – feeds such as maize, barley and triticale.

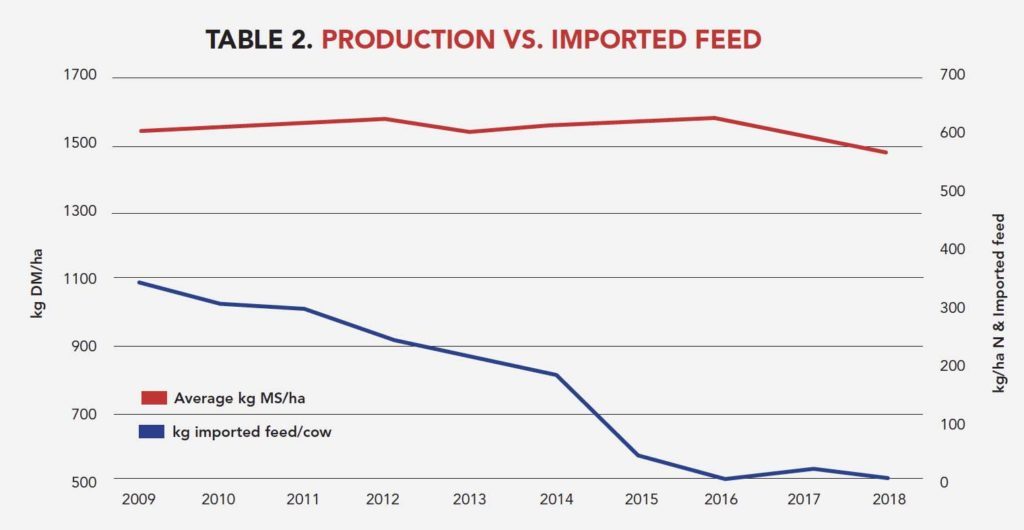

Despite pulling out supplement, production hasn’t changed.

“I think that tells us we had a higher degree of substitution than we thought – even though we thought we were doing a pretty good job.

“It means our productivity has increased with less input so our grass harvested must have lifted,” Greg says.

Stocking rate hasn’t really changed over time and sits at about 3.6cows/ha with milk production per cow at 420-440kg milksolids (MS) and 1550kg MS/ha.

Greg agrees production can’t be ignored and it’s important stocking rate is set so that cows can be well fed on pasture alone through the front half of the season and a normal autumn season.

If conditions mean pasture targets can’t be met through the autumn, then other tools such as early culling and drying off are used rather than bringing in supplement. Again their aim is to maximise the margin by focusing on the cost part of the equation.

“We avoid any kind of solution that aims to push that margin by diluting costs with extra production.

“If we’re weighing up a decision that may or may not produce more milk we’ll opt for the decision that may mean less milk but always means less cost.”

Greg says the first step in pulling feed out was to consistently achieve 1500kg DM/ha residuals and train both the people and cows in achieving that.

“Every paddock, every day – it had to be fine-tuned.”

It meant using the feed wedge closely and people spending more time in the paddock with cows monitoring their progress getting through their allocation.

“It meant breaking down the grazing schedules into half-hour intervals and ensuring cows were never hanging around at a 1500kg DM/ha residual. They’d get shifted the minute they hit it. If they didn’t they’d go back into that paddock until they did,” he says.

If they hit their residual target by 11am, Greg says that would set off a trigger and start questions going in the team’s minds.

“It sort of sets off an alarm and they come to the contract milker and the contract milker will mention it to me and we’ll look at what’s happening – have we got the paddock selection right, where’s the deviation and what should we do about it?

“It’s a sort of feedback loop that’s operating. We do a lot of informal email comms where every two or three days I’ll put up the KPIs around the group and we’ll look at whether we’re going too fast, too slow, have we got the right paddocks shut up at the right time?”

Greg has spent hours walking paddocks with staff, talking about and estimating covers, discussing pre-graze and post-grazing levels, growth rates and average covers – everyone needs to be on the same page and be calibrated.

Greg and Rachel’s contract milker, Steve O’Sullivan is on all three of their own farms. He’s also a partner in their equity partnerships.

Steve’s been in their business for 18 years and staff turnover is virtually non-existent.

That means consistency over how staff view and estimate pasture covers and makes the by-eye approach accurate.

That accurate assessment includes taking into account cow behaviour and interpreting what they’re telling you about your estimates of pasture cover, Greg says.

“If you solely rely on a platemeter you’re going to come up with some wonky information,” he says.

It’s good for setting up the wedge but you need to be considering other factors such as drymatter percentages when making the assessment on cover.

“During farm walks they’ll be saying ok what do we think this is, how many metres have the cows had, how much have they harvested, what’s the residual and so what did the pre-graze have to be?

“Those are the sorts of questions we’ll run through when we’re out in the paddock together too.

“I want the guys to be thinking about what they’re seeing and assessing the whole picture every time. If you empower them to think about it and justify their reasoning, it becomes first nature.

“If they’re just going by the platemeter reading they’re not going to have those skills.”

Growing more grass

As well as utilising more, Greg and Rachel have increased the amount of drymatter grown on the farm by reviewing and upgrading irrigation, soil moisture monitoring and being more precise with their soil fertility.

“Irrigation is a big expense line item so it gets a fair bit of notice. Just like any other component the more you monitor and measure it the more control you have over it,” Greg says.

Soil moisture monitoring via Aquaflex tapes and telemetry of that data along with data on evapotranspiration and weather forecasts means they can be a lot more accurate with irrigation scheduling.

“We’ve been trying to operate at the lower end of the soil moisture band.

“Back in the early days the view was you couldn’t put too much water on and once the machines were turned on they had to stay on just to keep up.

“But we’ve found by investing in enhancing the irrigation systems and monitoring we’ve been able to move a little close to the cliff in terms of soil moisture levels and we’ve been able to do that without detriment to pasture yield.

“At the same time, we’ve reduced water use and loss to ground water of both water and nutrients.

“The return on capital for soil moisture monitoring is very high. Irrigation costs us (across the four farms) about $1500/day so we only have to turn it off for two or three days and it’s paid for itself.”

About 95% of the water for the farms is sourced from ground water bores so pumping is a significant cost.

The other 5% is from the BCI scheme and two of the couple’s farms have storage ponds to increase reliability of that water.

Greg and Rachel have moved to soil testing every paddock and have a good paddock-by-paddock data set on soil fertility. While he knows it’s a multifactorial issue Greg’s analysis, correlating yields with Olsen P values, found a pretty poor relationship and while being careful to make sure paddock yields aren’t being affected by any other major issues, it’s led him to reduce his target Olsen P level to 25.

“I’m trying to position that fertility close to the top of the steepest part of the response curve and that’s meant we’ve been able to save on fertiliser costs.

“Moving to whole farm testing has been very powerful in terms of being able to mine your top end, put it on where it’s needed and get good responses.”

Managing a nil input system

Greg starts his 101 Guide to Managing With No Inputs in the autumn because that’s when the next season is set up.

“We use targeted average pasture covers that are non-negotiable through the autumn so that we end the season exactly where we want farm average cover to be.

“We won’t compromise a single kg of grass to eke out a little more milk.”

They have 5% of their milking platform in fodder beet and use half of that for autumn transitioning cows. Their average farm cover, dry-off target is 2000-2100kg DM/ha.

“The flex will be what our winter feed situation looks like,” Greg says.

When the new season rolls around they are disciplined in using a simple spring rotation planner to allocate a specific area to cows based on a square metre rate per cow calved.

They’ve made it clear though that if they were to get a severe weather event over that time they’d purchase feed in.

“We have that backstop because when you get close to the edge you have to give the guys confidence that they’re not going to tip over.”

During that time, they’re monitoring both their daily allocation closely and weekly pasture covers so they have the spring rotation planner and target pasture cover graphs for the farm teams to track too, with the graphs driven from the feed budget.

“So they have two points of reference and we won’t act unless there’s an issue with both.”

From balance date on, the average pasture cover and pre-grazing covers are the key KPIs and with weekly pasture cover monitoring for each paddock across the whole farm they use a simple feed wedge to show any impending feed deficit or surplus.

At times of rapid or variable growth they’ll walk the farm every five or six days but they’re also assessing paddocks as they’re going into them each day.

The aim is for a pre-graze cover of between 2800-3000kg DM/ha which translates to a 2100kg DM/ha average cover across the farm and a grazing interval of about 21 days.

The farm is mostly in diploid ryegrasses and Greg finds 21 days gives the right balance between getting close to a three-leaf stage and maintaining quality.

FARM FACTS

Roadley Farms

Total effective area: 570ha

Total support area: 172ha

Total cows: 2060

Average production: 1550-1600kg MS/ha, 420-440kg MS/cow

Supplement: Nil

Farm working expenses: $3.20-$3.40 including market rate for support costs

Return on capital: Aiming for minimum 9% on any investment.

Return on equity: Long run ROE 18%.