Where to for world farmers?

California’s farmers face a range of issues, forcing some to abandon traditional agriculture. By Elaine Fisher.

Cyber-attacks, theft of crops, access to water, climate change and labour shortages are among the issues causing some North American farmers and growers to change their land use away from food production.

Cyber-attacks, theft of crops, access to water, climate change and labour shortages are among the issues causing some North American farmers and growers to change their land use away from food production.

That was among findings outlined in an AgriTech New Zealand webinar presented in February by Lucie Douma, 2022 Nuffield New Zealand Farming Scholar and Ministry for Primary Industry’s Covid recovery and supply chain manager.

Hosted by Kylie Horomia, community engagement manager for AgriTech New Zealand, the webinar was called Global AgriFutures Insights – How can NZ respond to overseas trends? During the online session, attended by about 330 rural professionals, Lucie outlined the findings of her recent visits to North America, United Kingdom and Europe. Cyber attacks had the potential to disrupt the sowing of crops by machinery using GPS navigation in North America’s ‘Corn Belt’.

“All the planting is done over an intense three-week period, using GPS, so a cyber attack which disrupted that would mean a reduction in corn and soy yields.

“The US government is looking closely at how susceptible that industry is to cyberattacks and how to protect it,” Lucie said.

Some growers of high-value crops were employing ex-navy Seals as security guards after cases of cartels moving in at night before harvest, to strip trees of crops like pistachio nuts or harvest cannabis, she said.

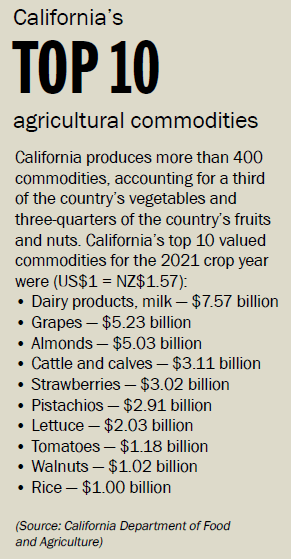

By far the biggest threat was lack of water, especially in California, the US’s largest producer of food, growing two thirds of North America’s nuts and one third of its fresh vegetables.

However, its climate is changing, and Lucie said access to water is of increased concern.

“I spent time in the San Joaquin Valley which is an important food and grape-growing area.

“The region, which is in a flood plain, does not get a lot of rain but does get a lot of fog close to the coast.

“Growers rely on water from snow melt in the Sierra Nevada Ranges. Snow forms giant reservoirs, providing water when it slowly melts but, partly because of the forest fires in the mountains and climate change, snow is not settling and is melting a lot quicker than usual.

“The region has experienced three years of drought and how to manage water is a major issue.

Each county within California manages its own water allocation in an individualistic approach which doesn’t account for growers further down the supply.

“Up to 40% of the land is flood-irrigated with river water. One of the reasons is to recharge the land but there’s an economic reason too as it could cost up to $US400 more per acre for mechanical irrigation. However, flood irrigation is not a good way to manage water, with much of it evaporating.”

Lucie said water restrictions were among the reasons some growers, including Woolf Farms, were converting some of their land to other uses.

“Woolf Farms, which has 25,000 acres (10,000 hectares) of land and grows tomatoes and almonds, is moving to non-food crops, carbon sequestration and solar energy.”

Among the options are drought-tolerant crops such as agave, the feedstock for products like tequila and mezcal. Woolf Farms also has plans to convert former cropland to solar installations. Lucie says the company is not alone in seeking alternatives to high-cost food production.

“Stuart Woolf thinks that in the next few years, he will stop growing on 30 to 40% of his land. If this happens on scale in California, some figures show that in the next few years up to one tenth of the land or half a million acres will not be used for food production by 2040.”

That posed a huge food security threat for North America and ways to address it included vertical farming under which crops grow in vertically stacked layers, often in controlled environments and soilless techniques such as hydroponics. Lucie saw similar trends in energy and food farming in the Netherlands where wind and solar generators are interspaced alongside crops.

There were however, marked differences in public attitudes to farmers and farming between North America, UK and Europe.

“In North America people are proud of farmers and farming and the quality of food produced. Some restaurants even showcase food from specific regions with the provenance stories of where it is produced and by who.”

In Europe, including the Netherlands and UK, the impact of Covid isolation, social media and TV channels like Netflix showing a one-sided aspect of farming, had had a huge impact on public perception.

“Many farmers are not proud to be farming any more. They don’t want their children going into farming and are planning exit strategies, which is sad to see.

“In the UK there has been a big rise in activism with environmental, vegan and animal welfare groups sharing resources to have a powerful impact on public perception. We saw something of that in New Zealand with activist group slashing tyres of people driving utes.

“In New Zealand we need to support our farmers and growers who are under a lot of pressure including from water challenges and adverse weather events.”

Labour costs and supply were issues common to NZ, California, Scotland and Europe, Lucie said. The availability of cheap labour had been impacted by the Covid pandemic and in Scotland, also by Brexit, where farmers were now relying on a domestic labour force, which often proved unreliable. This had added impetus to the need for innovation, including robotic harvesting, an area NZ tech companies could benefit from, she said.

However, NZ tech companies should not try to ‘go it alone’. Her recommendation was to work globally and build relationships with other countries and tech companies to meet the needs of a rapidly changing world. Lucie said NZ should focus on producing high-quality, premium foods for the world, rather than compete in the commodity space. She also believed the dairy and meat industry had a strong future.

“It’s my personal view that animal farming is not a sunset industry. Its future is as a niche industry in the premium space. People may not be able to afford to eat meat every day, but meat will not go away. Humans have eaten meat ever since we have been on the planet.”

HARVESTING the bugs

IT’S AROUND 10,000 YEARS since animals were first domesticated, but now scientists in the United States are working to domesticate microbes to produce food for humans.

Lucie Douma, 2022 Nuffield New Zealand Farming Scholar and Ministry for Primary Industry’s Covid recovery and supply chain manager, told those who attended the AgriTech New Zealand online webinar in February that this ‘sci-fi’ approach to food security was under development now.

“The USA’s Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has a project called, Cornucopia, using microbes, water and electricity to produce nutritionally balanced food. Its stated aim is for every household to eventually have its own little device to produce food,” she said.

“Cornucopia seeks to enable deployable, on-demand production of appetizing, microbial-origin food starting from water, air, and electricity with minimal to no supplementation,” the DARPA website says.

“If successful, the programme could significantly reduce the logistical burden of food transportation associated with deployed military operations and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) operations.

“To address vulnerabilities in food supply chains across a variety of operational and humanitarian scenarios, Cornucopia will demonstrate the capacity to produce all four human dietary macronutrients (protein, carbohydrate, fat, and dietary fibre) in ratios that target Military Dietary Reference Intake (MDRI) daily requirements for complete nutrition. Outputs will be in multiple food formats (e.g., shake, bar, gel, jerky) that meet military nutritional standards and palatability requirements in a system minimising inputs, handling, and footprint.

“Cornucopia is a four-year programme with three focus areas: domestication of microbes for human consumption; tailorability of microbial-origin food for different flavours, formats and nutritional composition; and integrated system demonstrations benchmarked by two military use cases, a small forward-operating military unit in austere conditions and a HADR scenario.”

(Source: https://www.darpa.mil/program/cornucopia)